Russia’s lack of conventional military superiority when compared to the U.S. and the rest of NATO is driving its development of “asymmetric” capabilities like the nuclear anti-satellite weapon that generated headlines earlier this year, multiple Pentagon officials said this week.

In turn, increased aggression by both Russia and China is driving larger questions about how the U.S. can deter conflict, particularly in space, senior leaders said during events around the globe.

When the White House confirmed reports in February that Russia was developing nuclear weapons to target satellites, national security leaders warned that such a weapon would have devastating effects not only for the U.S. military but for the entire global economy.

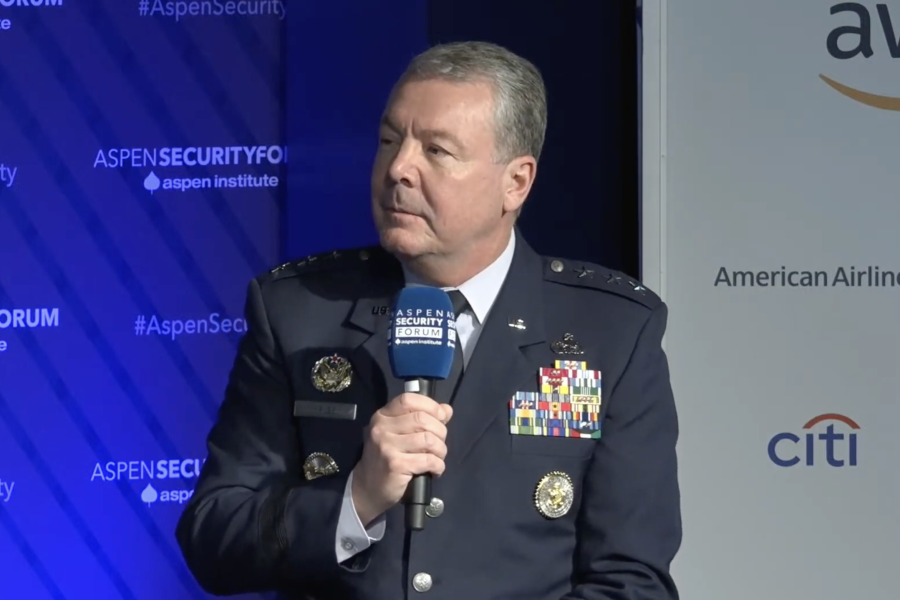

At the Aspen Security Forum in Colorado, U.S. Space Command boss Gen. Stephen N. Whiting said July 17 a space nuke “would affect United States satellites, Chinese satellites, Russian satellites, European satellites, Indian satellites, Japanese satellites, and so it’s really holding at risk the entire modern way of life.

But the Pentagon has known about the program for years, said Defense Intelligence Agency director Lt. Gen. Jeffrey A. Kruse.

“None of this is news breaking,” Kruse said in Aspen. “We have been tracking for almost a decade Russia’s intent to design the ability to put a nuclear weapon in space. They have progressed down to a point where we think they’re getting close, and so that was a lot of the discussions that you saw in the media.”

Kruse thinks Russia’s interest in nuclear space weapons reflects the state of its military after more than two years of brutal, indecisive warfare in Ukraine.

“Their lack of conventional superiority drives them to asymmetric solutions,” he said. “They see this as a potential pathway that they might want to pursue. The exposure of it will potentially change their path. I am not sure that we know that yet.”

Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy Vipin Narang echoed the “asymmetric” point at the Center for a New American Security on July 19, saying Russia can afford to target space because its military and economy is less dependent on satellites than those of other countries.

“We are so dependent on space for our way of life, but also the way we prosecute and wage wars. Space is critical to the joint force,” Narang said. “And Russia is not as dependent on space for its way of life or the way it prosecutes wars. And so Russia sees that asymmetry.”

Indeed, while Whiting described the Soviet Union as the “original space superpower,” observers have noted that those capabilities declined over the years and are far from what they once were. In Ukraine, experts say the Russians have used their space assets to some effect but failed to take full advantage.

“Russian forces have struggled to both collect sufficient tactically useful information from satellites and disseminate that information to warfighters in a timely manner, due to their rigid command structure,” Robin Dickey and Michael P. Gleason wrote in April for an Air University journal.

“Russian space capabilities do not play a significant role on the battlefield,” Center for Strategic and International Studies fellows Clayton Swope and Makena Young wrote in June. “Russia’s version of GPS, called GLONASS, is extremely unreliable.”

Narang also noted that Russia has fallen behind the U.S. and NATO in most military areas besides nuclear, where the country sports an inventory of low-yield “tactical” nukes, despite their outsized impact.

“I prefer to refer to them as treaty-unaccountable nuclear weapons, because any use of nuclear weapons will fundamentally change the character of conflict and has strategic impact,” Narang said.

Similarly, a nuclear weapon in space may not directly kill any humans, but its impact would be broad, and the U.S. must convince Russia that deploying such a weapon would be irresponsible, impractical and hard to control, Narang argued.

“Command and control on terrestrial Earth is hard enough,” he said. “How are you going to command and control this thing and have confidence that you can command and control? And what happens if you cannot?”