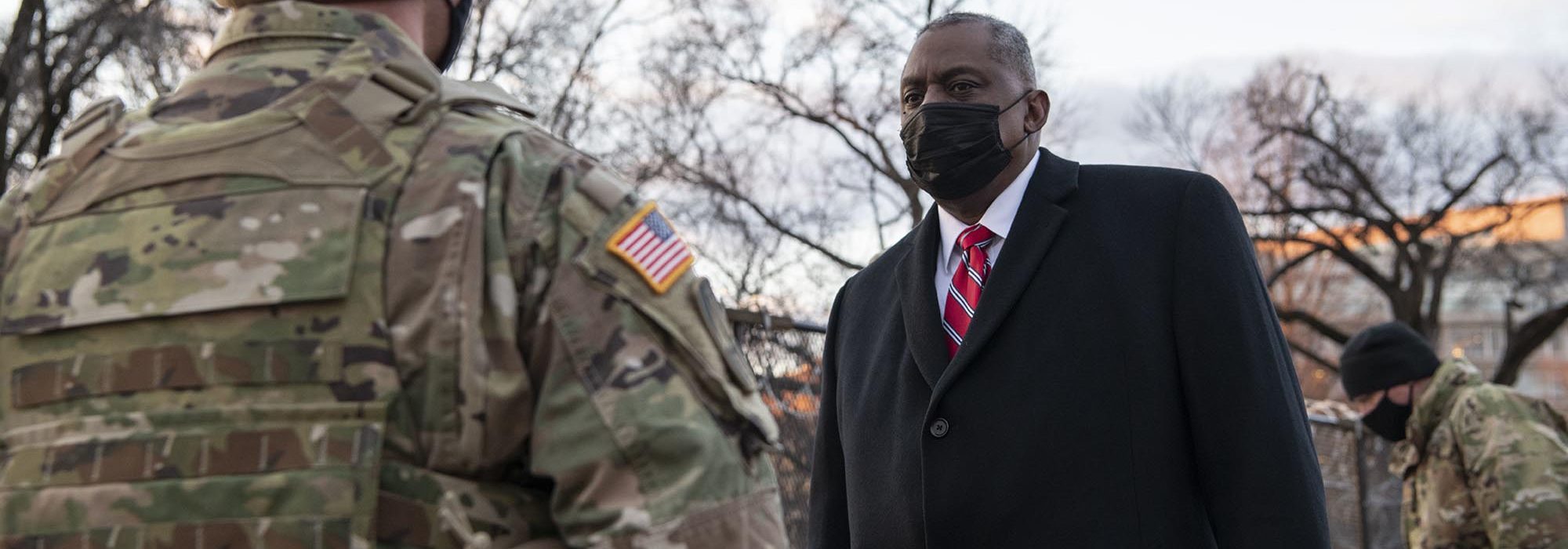

The Austin Era

Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III—and the Biden administration—is likely to refresh alliances during his tour at the Pentagon, but probably won’t make drastic changes to the National Defense Strategy (NDS) and won’t try to dissolve the fledgling Space Force. While he personally supports the NDS and the nuclear triad, he will preside over a new review of nuclear posture. Competing effectively with China and Russia, at flat or lower levels of defense spending, will likely occupy much of his attention.

President Joe Biden’s only reference to the military in his Jan. 20 inaugural speech was directed to allies, and could be interpreted as Austin’s marching orders. “We will repair our alliances and engage with the world again,” Biden said, pledging that the U.S. will be a “strong and trusted partner for peace, progress, and security.”

President [Donald J.] Trump’s “America First” approach to alliances unsettled some allies and raised doubts as to how strongly the U.S. would honor its mutual defense treaty obligations. Under his administration, Biden promised, the U.S., will “lead by the power of our example.”

Not surprisingly then, Austin’s first official calls after his swearing-in were to the Secretary General of NATO and the defense ministers of Japan and Korea.

A former four-star Army general, Austin was confirmed by the Senate Jan. 22 by a 93-2 vote. The Senate had already waived the statutory rule that a former officer be out of uniform seven years before taking the top Pentagon job. Austin retired in 2016 after heading U.S. Central Command for three years. He previously served as the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, and director of the Joint Staff.

Austin and Biden met when Biden’s son Beau was on Austin’s staff; the two attended Catholic services together. As CENTCOM chief, Austin was a trusted general during the Obama administration, his “strategic patience” mantra resonating with the White House. Austin advised an arm’s-length involvement in support of Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, and quietly urged diplomacy over military action whenever possible. A 1975 West Point graduate, he’s regarded as having been an effective field commander

In his confirmation hearing, Austin pledged to surround himself with “empowered, experienced, capable civilian leaders,” and not be unduly influenced by uniformed leaders. He said he will work hand-in-glove with the State Department and promised to be “transparent” with Congress.

Austin voiced agreement with the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which reset the U.S. strategic priority away from the fight against violent extremism to “great power competition” with China and Russia. During confirmation testimony he called China America’s “pacing threat.”

Austin promised a new national defense strategy review in 2022. “Our resources need to match our strategy and our strategy needs to match our policy,” he said. Future defense spending is anticipated to hold flat or decline in the coming years as Congress seeks to balance security investment with COVID-19 relief.

After retiring from the Army, Austin served on several boards, including that of Raytheon Technologies, the Pentagon’s No. 2 contractor. He has promised to recuse himself from decisions involving the company throughout his tenure.

First Order of Business

The Pentagon’s synopsis of Austin’s call to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said the two discussed “the importance of our shared values,” the current security environment, NATO deterrence and defense posture, and “the ongoing missions in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

In the call with Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi, Austin promised to maintain the readiness of the nearly 55,000 U.S. troops in Japan, and that the U.S. would respond militarily to any attack on the Senkaku Islands in East China Sea, controlled by Japan but claimed by both China and Taiwan. Kishi told reporters afterward that the two nations will “oppose any unilateral attempts to change the status quo” in the East and South China Seas.

In his call with South Korean Defense Minister Suh Wook, the two agreed on “the need to maintain the readiness of alliance combined forces,” the Pentagon said in a summary. Austin noted the “ironclad” nature of the two nations’ relationship. No mention was made of whether the U.S. and South Korea would resume large-scale exercises, discontinued by Trump in an agreement with North Korean “supreme leader” Kim Jong Un.

Austin’s other first order of business was to meet with senior Pentagon leaders, including Joint Chiefs Chairman Army Gen. Mark A. Milley, on DOD response to the COVID-19 pandemic. He told the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) that supporting vaccine distribution would be a top priority upon taking office.

Austin told the committee he “personally” supports the nuclear triad and opposes unilateral reductions to the U.S. strategic arsenal. He promised to review strategic modernization efforts, of which the Air Force is pursuing three simultaneously: the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, the B-21 bomber and the Long-Range Stand- off weapon.

Austin said he would study the Navy’s recommendations to sharply increase its size.

On Keeping Space Force

In written questions from the SASC before his confirmation hearing, Austin was asked whether he thought the creation of Space Force was warranted, and his response was noncommittal. The defense space enterprise, he wrote, is “still not well-integrated with other services and terrestrial commands,” and there are “several other challenges that will need to be addressed—as would be expected”—when standing up a new service, Austin wrote.

Yet that lack of a clear endorsement should not be seen as a change in direction, said Todd Harrison of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The chances of the new service being unmade are “close to zero,” he told the Associated Press. The push to create a Space Force had congressional backing even before Trump came to office, and its bipartisan support signals that Congress perceives a U.S. vulnerability in space. Pushing to repeal the Space Force would be an unwanted point of conflict.

Retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, head of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, said the Space Force is “underfunded and undermanned.” It lacks the authorities to “consolidate the more than 30 other organizations” with a role in force design and architectures of military space capabilities. “To reduce costs and duplication of effort, these organizations must be consolidated under the Space Force,” Deptula said, arguing that this should be a goal for the new administration.

Byron Callan, defense analyst with Capital Alpha partners, wrote to investors that they shouldn’t conclude that Army programs will disproportionately benefit from Austin’s background.

“We observe that the most senior DOD leadership generally thinks of the joint force, rather than promote service-parochial interests,” Callan wrote.

However, a former senior Pentagon official countered that “there are now two Army four-stars at the top of the Pentagon and that’s not conducive to diversity of perspective on advice rendered to the President from a military viewpoint. They’ll need to broaden their view.”

Austin marks the third, ground-oriented career military officer to lead the Pentagon in four years, following former Marine general, Jim Mattis and Mark Esper, a former Army officer.

Kathleen Hicks, recently of the CSIS, will be Austin’s deputy. As principal deputy undersecretary for policy in the Obama administration, she oversaw the 2012 defense strategic guidance, which sought to align military strategy with the looming defense spending restrictions imposed by the Budget Control Act. That guidance—which emphasized preparation for future wars, a focus shift from Europe to the Pacific theater, “freedom of navigation” operations, and greater emphasis on special operations forces and advanced technology—was mirrored by the 2018 NDS in all ways, except its push to shrink the Army and Marine Corps. Hicks was also the main architect of the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review; criticized in some quarters for a “do-everything” approach detached from resource limits.

Hicks “has the discipline, intellect, and organizational skill to make the Department work effectively,” said former Deputy Defense Secretary and CSIS President John Hamre, in an interview with Breaking Defense. She served on the board of the U.S. Naval Institute and as a trustee for the Aerospace Corp.

Callan wrote that Hicks’ public comments on defense indicate she’ll bring “a sharp focus” to “alignment between budgets and military concepts of operations vs. China and Russia,” as well as a “closer examination of those concepts and theories of victory.” He added that she will likely lead “a bigger push on DOD innovation and experimentation” and “work within DOD budget resources and not simply ask for more that’s unlikely to be realized.”

Divesting Legacy Systems

Callan is less confident that under Austin, the Air Force will be allowed to follow its stated plan to divest older systems and apply the savings to new gear and capabilities.

“The A-10 was the poster child” for the Air Force being rebuffed on that approach, Callan said. Especially in a time of high unemployment driven by the pandemic, members of Congress will be loathe to agree to anything “that potentially cuts jobs in their districts or constituencies,” he said. While the Air Force has kept mum about such retirements beyond reducing the size of the B-1B bomber fleet—which Congress approved—further cuts are likely to be seen as having “immediate detriment” to local jobs, Callan observed.

Callan doesn’t see a big reduction in arms sales under the new administration. Countries that may have held back requests for systems like the F-35 because of their “concern about U.S. commitments” to mutual defense under the previous administration may feel more inclined to move ahead, he said. Biden’s defense team will be cooler to sales of precision weapons to Saudi Arabia, given concerns over their use in the Yemen war, but it is unlikely to do “an about-face on Taiwan,” he added. Trump’s move to lift restrictions on foreign sales of unmanned aerial systems is also unlikely to be reversed “because of market realities,” Callan said. If the U.S. withholds those systems, China and others will willingly fill the void, costing the U.S. influence with customer countries.

Biden’ defense picks are “solid,” Deptula said, calling them “effective advocates” for a strong defense. That said, the defense budget in the Biden administration will be lower than current levels. That’s of great concern to the Air Force and Space Force, because they both face daunting demands.

The Air Force particularly is facing “immense pressures” due to having the “oldest and fewest” aircraft it’s ever fielded, and having taken more budget reductions than any other service “since the Cold War ended,” Deptula said. Austin and Hicks will have to be “transparent regarding what they need and what they can afford.” He added that “it’s okay to have a gap, as that’s a way to measure risk, but they shouldn’t pretend the problem doesn’t exist.”

Just Passing Through

Deptula urged that Austin’s team finally do away with the “pass- through” budget idiosyncrasy that makes it look like the Air Force budget is as much as 20 percent larger than it really is.

“Money over which the Air Force has no control must be separated from its budget to ensure accurate understanding of its actual budget,” Deptula asserted. Most of the pass-through goes to the Intelligence Community, but “the negative effect” of the pass-through “is real and must be stopped to ensure transparency in defense spending.”

Callan predicts even greater emphasis on experimentation and prototyping under Austin.

“I think that’s where they’re going to put their eggs,” he said. The approach will be, “let’s see how we can use technology to substitute for capacity, or use technology to make trades at the margin for force structure, or different kinds of force structure … to plug those gaps.”