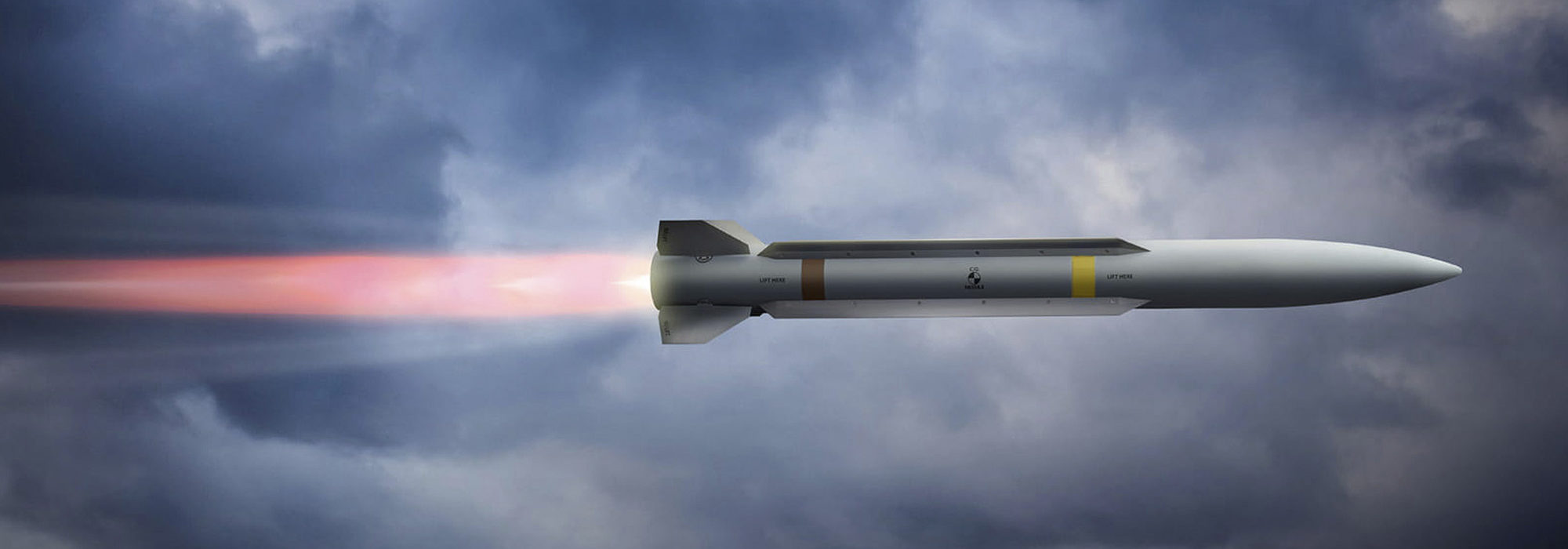

The future of munitions is coming into focus, promising increased speed and range, shared components, stealth—and even collaborative capabilities.

When the Air Force flies into combat, it does so with the same portfolio of tactical weapons it’s used since the 1990s and early 2000s. Many date to before the 1991 Gulf War.

Adversary air defenses have gotten a lot tougher since Operation Desert Storm, however, and what was unthinkable 30 years ago—an enemy that could shoot down, blind or jam individual high-speed munitions—is now very likely. High-fidelity and long-range air defense radars and sensors in the hands of potential adversaries—in rapidly proliferating numbers—paired with new interceptor weapons are making it harder to hit the most well-defended targets.

A new generation of precision weapons is needed to enhance modern strike capability and deter potential aggressors.

“We need fifth-generation weapons to go with our fifth-generation Air Force,” said Gen. Mark D. Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, in October 2021, counting such munitions among his top five priorities.

What exactly “fifth generation” weapons are isn’t well defined, though. Kelly framed his comments in relation to fifth-generation combat aircraft—the F-22, F-35, and B-2—which combine stealth and fused sensor data for superior situational awareness. But those platforms are still employing weapons designed for fourth-generation fighters. Kelly needs new munitions that can extract maximum effect from all the capabilities of modern stealth aircraft.

ACC Commander, Gen. Mark KellyWe need fifth-generation weapons to go with our fifth-generation Air Force.

Brig. Gen. Jason Bartolomei, program executive officer for weapons and head of the Air Force’s armament directorate, declined to offer a “black-and-white” definition for fifth-gen weapons, but said in a January interview that“what we’re talking about there is making sure that we have effective weapons to support the missions” required.

“It’s hard for me to focus on any specific attribute,” he said, noting that “since antiquity” weapons have been pursued for “the same basic attributes”—presumably speed, lethality, and surprise—“and how we achieve those different attributes have changed with technology.”

“We just have to keep pace with the adversaries and…the changes in the technological environment,” he said.

Retired Air Force Col. Mark Gunzinger, director of future concepts and capability assessments at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies and a former deputy undersecretary of defense, said the Air Force “has a real problem.”

The Air Force fleet is “too small, not survivable enough, doesn’t have enough range, and doesn’t have enough lethality for the kinds of conflicts it’s now being asked to prepare for,” Gunzinger said. USAF is struggling to find “the right mix between shorter range fighters, longer-range bombers, [and autonomous] collaborative combat aircraft … what their payload should be, what the ranges should be, what their degree of survivability should be, and how much should be standoff versus penetrating.”

On The Way: 10 Fifth-Generation Weapons Now in Development

The Air Force is exploring a host of new air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons to fill roles from direct-strike bombs and standoff ground attack missiles to long-range dogfight missiles.

Not all will ultimately enter service, but with modularity a consistent theme, some elements could still join the inventory.

Not all will ultimately enter service, but with modularity a consistent theme, some elements could still join the inventory.

This list was compiled from answers to inquiries, industry day briefings, and budget documents. Other weapons, still classified, are also likely in development.

Air-to-Air Missiles

AIM-260 Joint Advanced Tactical Missile (JATM). This radar-guided dogfight missile will be about the same size as the 30-year-old AIM-120 AMRAAM, but with considerably longer range. Built by Lockheed Martin it was first revealed in 2019. Little has been revealed since, but USAF has acknowledged that live tests were conducted in 2020 and 2021. The JATM’s enhanced range is greater than China’s PL-15—in many ways, an AMRAAM clone, restoring the “first shot, first kill” advantage to U.S. aircraft. The Navy and Army are said to be collaborating with USAF on JATM.

Long-Range Engagement Weapon (LREW). Another potential AMRAAM successor or JATM complement. Built by Raytheon, the LREW is reportedly a larger missile that can only be carried externally on fighters, and may be intended to shoot down adversary airborne warning systems, tankers, or bombers at great distances.

Modular Advanced Missile (MAM). Possibly a successor to the AIM-9X short-range dogfight missile, the MAM will have stackable propulsion units and interchangeable seekers. Built by Boeing, the MAM contracts also support other company projects, such as the Compact Air-to-Air Missile (CAAM), Extended-Range Air-to-Air Missile (ERAAM), and Long-Range Air-to-Air Missile (LRAAM). The ERAAM/LRAAM may be a competitor to Raytheon’s LREW.

Peregrine. This Raytheon concept would combine the capability of the AMRAAM with longer range in a package only half the size. Raytheon received Air Force Research Laboratory funding to explore Peregrine in December 2022; previously, it was a self-funded program.

CUDA. A Lockheed proposal that AFRL began evaluating in 2019 under the Small Advanced Capabilities Missile project, the CUDA would also be half the size of AMRAAM, steered with a unique system of propulsive bursts from around the rocket body.

Hypersonic Missiles

AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW). The ARRW is USAF’s large, quick-and-dirty entrée into hypersonic missiles—those that travel at more than five times the speed of sound. Intended for use against high-value or mobile targets where speed of attack from standoff range is crucial, ARRW accelerates to hypersonic speed with a rocket, detaches, and then maneuvers as it glides to its target. The Lockheed Martin weapon has accumulated several successful flight- tests after a string of failures, but USAF officials are mum on how many it plans to build. Part of Lockheed’s contract is to demonstrate it can be produced affordably. A B-52 can carry four ARRWs on its wing pylons. The B-1B and F-15EX may also be equipped with it.

Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM). Raytheon won the HACM competition in September 2022, with an initial operating capability eyed for around 2027. The missile is a ground-attack weapon using an air-breathing, scramjet engine, and will be small enough to be carried on fighter-sized aircraft; the F-15EX has been mentioned as a likely platform. It builds on the Air Force-DARPA Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC).

Ground-Attack Weapons

Stand-in Attack Weapon (SiAW). The Air Force awarded competitive SiAW contracts to L3Harris Technologies, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman in May 2022. The weapon is intended to be a Suppression/Destruction of Enemy Air Defenses successor to the High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) in use since the 1980s. Intended as a pathfinder weapon to clear out defensive radars and surface-to-air weapons, SiAW will add ballistic missile launchers and other time-sensitive targets to its target list. The weapon must fit inside the F-35 weapons bay. Once a contractor is selected, a 2026 operational capability is contemplated.

Stand-off Attack Weapon (SoAW). The Air Force formally announced its SoAW competition in September 2022 and specified that it’s looking for multiple vendors to produce the chosen design, which USAF intends to own. The Air Force didn’t disclose its range requirements for SoAW; it may be intended as a lower-cost standoff weapon to fill the niche of the AGM-158 Joint Advanced Surface Standoff Missile–Extended Range (JASSM-ER) and its close kin, the AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM).

Global Precision Attack Weapon (GPAW). Likely to be the successor to JDAM—USAF’s family of direct-attack, GPS-guided bombs—the GPAW was announced in the fall of 2020. The service wants small, lightweight weapons to strike surface targets as well as hardened or deeply buried targets, yet affordable in large numbers. The weapon is supposed to have advanced sensors and a degree of autonomy. The GPAW is to have an open architecture and be compatible with advanced as well as legacy aircraft, with a “cockpit-selectable warhead effect.”

The same problem afflicts the weapons portfolio, he said. Today’s stockpile of precision-guided munitions “is too small for peer conflict … lacks survivability [and] … is skewed …toward the shorter range,” according to Gunzinger. The Air Force has to find “the sweet spot—or balance—between range, warhead size, degree of survivability, speed, and the cost of its [precision guided munitions].”

In a November 2021 paper titled “Affordable Mass,” Gunzinger pressed the Air Force to develop “a family of affordable, next-generation, mid-range (50 to 250 nautical miles) air-to-ground PGMs that can be carried in large numbers by its fifth-generation fighters and stealth bombers.”

The Air Force is clearly headed in that direction. Based on comments from senior service leaders, think-tankers and industry experts, fifth-generation weapons likely share certain key characteristics:

- Stealthy. To get past modern defenses, weapons must be either low-observable by nature or employ electronic means to hide until they reach the engagement endgame. They must be resilient against electronic attack and spoofing by cyber techniques.

- Faster. Some fifth-gen weapons will be extremely fast, so that even when detected, they are too hard to intercept before they hit their targets. This is the idea behind hypersonic weapons now in development.

- Longer-Ranged. Striking from much greater distances than current weapons is a crucial capability in order to launch before coming within range of an enemy’s weapons.

- More Compact. To remain stealthy, advanced aircraft must carry weapons internally. Miniaturized electronics and novel propulsion methods can make new weapons smaller, increasing the number of weapons each aircraft can carry. Smaller weapons will also be essential as USAF develops collaborative combat aircraft—uncrewed, autonomous “wingmen” likely to be more compact than crewed aircraft and carry a smaller payload.

- Modular. USAF has solicited industry for weapon concepts with “mix-and-match” seekers, warheads, and propulsion units. Modular designs could potentially increase production rates and reduce costs, while increasing manufacturing flexibility. Open architectures should make it easier to create a variety of strike options.

- Collaborative. Some fifth-gen weapons will be able to coordinate with each other to strike targets in the most effective sequence; to overwhelm a defender, to mask their objectives, or increase their survivability. The Air Force is experimenting with a number of such “swarm attack” concepts. New weapons will also collect information on the way to the target to feed the whole force’s understanding of the unfolding fight.

- Digitally Designed. Modern, computer-based design and modeling will enable the Air Force to run through thousands of design variations and options to achieve the optimal mix of capabilities and producibility.

Building a Munitions Roadmap

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall’s seven Operational Imperatives (OIs) define the capabilities the Air Force needs to present a credible deterrent to adversaries while laying the groundwork for victory if war becomes necessary. The OIs range from sensor/shooter networks to a resilient space architecture, the new B-21 bomber, and a future family of tactical combat aircraft, among others.

But Kendall also identified three capabilities that underlie the seven OIs. Those are airlift, electronic warfare, and munitions, which he calls “crosscutting enablers” because they touch nearly all the Air Force’s missions and can’t be considered in isolation. A team of operators and acquirers have been assigned to each of the three to organize and integrate them with the seven OIs and USAF’s broader plans.

Bartolomei co-leads the Weapons Functional Integration team, the task force organizing the crosscutting munitions effort. It aims to identify operational gaps in munitions and fill them in order of urgency. The resulting plan will inform budgets, starting with the President’s fiscal 2024 request.

While Bartolomei is the team’s co-chair for acquisition, Col. Christopher Buckley, chief of weapons development and requirements in the Air Force Futures shop, is the co-chair for operations.

The munitions roadmap is intended as a “living document” that will continue to evolve with progress in various programs, available funding, and the evolution of the threat, Bartolomei said.

Bartolomei said breakthroughs in sensors, propulsion, and effects technologies are coming rapidly, and the plan may therefore remain closely held.

“We live in a dynamic environment and things are changing … more frequently than I think anyone … is comfortable with,” he said.

The plan’s horizon is focused on the next five years, taking into account capabilities adversaries such as China are known to be developing.

Besides “really integrating and knitting together, very deliberately,” the operations and acquisition efforts, the munitions effort draws heavily on contractors and the science and technology community to inform the Air Force of the art of the possible, Bartolomei said, adding that the objective will be to define “the right capabilities for the mission sets we see emerging … but also … in the right quantities.”

In an email response to questions, Timothy P. Grayson, Kendall’s special assistant overseeing the Operational Imperatives and crosscutting teams, said expanding the military’s munitions inventory is crucial.

“Extensive wargaming and analysis demonstrates that limited capability, capacity, and upgradeability of the U.S. munitions inventory presents risks to our forces,” he wrote.

The U.S. needs “an affordable mix” of air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons “that can deliver the capability and capacity needed to maintain a competitive advantage over China—the pacing challenge,” he said.

Mix-and-Match

Bartolomei sees “a lot of value” in approaching new weapons development as a menu of modular components—seeker heads, propulsion, and warheads/effects—that can be put together in various combinations to address various kinds of targets. He envisions future weapons “being more open and modular.”

Discussions with industry focus on “how we’re partitioning the technical subsystem … how we’re thinking about the interfaces” to make modularity a reality, Bartolomei explained. This could also pay off in “our ability to produce” munitions at scale.

Modularity may also allow more “niche” weapons that could address small but crucial target sets, he said. “You could see …both those properties in our future weapons,” he observed.

A modular approach presents an opportunity to increase competition for more weapon elements, which could attract new competitors to the market, expanding the industrial base and potentially increasing capacity to surge production in a crisis.

The war in Ukraine has highlighted such risks, as most of the weapons the U.S. has provided are coming from U.S. war stocks. Replacing them will be a lengthy process, and in some cases could prove nearly impossible if components are long out of production.

More suppliers also guards against “vendor lock,” wherein the service becomes dependent on a single contractor for a given system’s upgrades and consumables.

The Air Force will “transition from proprietary, vendor-locked solutions” to one that applies “digital engineering, open-systems architecture, and agile software development,” Grayson said.

“The U.S. intends to increase its industrial base capacity to fulfill inventory requirements and sustain a conflict with a peer adversary, including sufficient volume of fire over an entire campaign,” he added.

Capacity Challenges

In a Pacific war, Gunzinger said, the Air Force could be tasked with striking “tens of thousands of aimpoints.” That means “you have to have weapons at scale that you can afford.”

With unit costs of $2 million a shot for some standoff weapons, and as much as $14 million per round for air-launched hypersonic weapons—to say nothing of projected $40 million to $50 million per shot for surface-launched hypersonic missiles—relying on such weapons isn’t economically feasible, he said. High-cost missiles might be appropriate for “incredibly high-value, time-sensitive targets” but can’t be a staple of a campaign.

“More speed can be part of the answer,” he said, “but there are other ways of achieving the survivability we need for striking into … highly contested threat environments.”

Gunzinger estimates the Air Force has enough weapons for only 10 to 14 days of moderate- to high-intensity strikes.

“And of course … we have to keep some in reserve,” in case another conflict erupts, he noted, adding: “We have to get the inventories up.”

According to his analysis, “the sweet spot is in mid-range weapons,” Gunzinger said. “That’s where you get the most effects” for the lowest cost, he added, “but it also allows you to have an attack density that can maintain pressure on the enemy.” If strikes only come every 48 hours, adversaries can recover because “there’s no stress on their system.” Only continuous strikes keep the pressure on. The munitions inventory must be sized “to impose a cost that will force” a quick conclusion to the conflict.

Grayson said the weapons inventory requires “the right mix” of “affordable standoff and stand-in munitions with sufficient capacity and capability needed to win in a peer conflict.” That mix has to be sustained over time, “so that we do not leave gaps in capability or capacity as we develop new weapons.”

Requests for information, industry days, and other industry involvement in the munitions dialog are “critical to the … process and [to] … help validate assumptions, identify the realism of development and fielding timelines, production capacities, and sustainment needs” to help USAF make its weapons decisions, Grayson said.

Production at Scale

William LaPlante, the Pentagon’s acquisition and sustainment czar, said munitions production needs to be rethought in order to meet projected wartimes needs. Speaking at the Potomac Officers Club in October, he said the Pentagon has accepted “just in time” supply of weapons in the recent past because that was all that could be justified in an ersatz “peacetime” environment. Weapons have also been a convenient bill-payer when budgets get tight, he said.

Now, however, as potential risks of conflict with China grow, munitions production takes on a new significance, LaPlante said.

“Production is deterrence,” he asserted.

The U.S. and its military partners and allies should have multiple factories able to mass-produce arms, LaPlante said. Weapons not only “interoperable, but interchangeable.” The U.S. and its allies can’t afford to depend on factories or vendors that represent potential single points of failure in the supply chain, he added. Weapons having a more modular design could help reduce such risks, he said.

Gunzinger agreed, saying “we need all hands on deck,” with NATO and other partners producing weapons “that can move between battlefields and employed by any member of the alliance or coalition.”

LaPlante also warned against “too much prototyping” and not enough production. Weapons in the lab aren’t a deterrent, he said.

The Pentagon and Congress agree that capacity must expand, but “we’re going to have to pay for it.” That will mean buying weapons the military may not ultimately need. “You have to hedge your bets,” he said.

A Sense of Urgency

Gunzinger worries that a national “sense of urgency” is missing, and that today’s lack of surge production capacity is “scary.”

Past assumptions that “we would have some time to surge production before we engage in combat; [or that] we can take six months to deploy to a fight, and have healthy stocks before we pull the trigger” are no longer valid, he argued.

“The assumptions we used to size our force and inventories …are gone,” he said. “We’re not going to have time to build up. Wars will start with little notice. They’re not going to be small. We’re going to have attrition like we’ve not seen since World War II.”

Gunzinger said China can see the problem the U.S. faces, and has an incentive to win “through exhaustion.” It’s “almost existential in terms of U.S. military posture across the planet, that there will have to be a significant investment [in munitions], but it can be done smartly.”

His prescription for the Air Force is to “maximize what you can buy today,” in stealthy standoff weapons and mid-range weapons, but get on with the next generation “as fast as possible.”

“The time has come to buy now, he said. “We just have to. Our inventories are too low, we don’t have the right mix, but we have some programs that can help with that in the near term. Don’t put it off to the future.”