The Air Force can leverage inexpensive, attritable drones to expand combat capacity in the Pacific and, perhaps, deter China from risking a war.

For the commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Adm. John C. Aquilino, China’s military buildup—and its growing coercive military behavior—is a daily worry. The timeline for competition between the U.S. and China to boil over into conflict could be “much closer to us than most think,” he told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2021. “We’ve seen aggressive actions earlier than anticipated, whether it be on the Indian border, or whether it be Hong Kong, or whether it be against the Uyghurs … that’s why I continue to talk about a sense of urgency,” Aquilino said. “We ought to be prepared today.” Gen. Mike A. Minihan, commander of Air Mobility Command, echoed those sentiments in a recent internal memo ordering his mobility forces to prepare for war as soon as 2025.

Airpower plays a central role in Aquilino’s plans. He has called for forward-based advanced aircraft that can operate in “contested space” west of the international dateline, closer to China, and “the ability to be expeditionary and move around the theater to places that matter when needed.” Such capabilities can demonstrate resolve, assure allies, and support the kind of posture needed to operate in a major war. But the U.S. Air Force doesn’t have enough fighters and bombers to go around, and its bases in the Indo-Pacific are increasingly vulnerable to Chinese air and missile attacks.

Maj. Gen. R. Scott Jobe, Air Combat Command director of plans, programs, and requirementsThe introduction of Autonomous Collaborative Platforms “actually changes the way we fight.”

The Defense Department’s plan to deploy newer and more advanced aircraft to Kadena Air Force Base in Japan is one piece to solve the INDOPACOM posture puzzle. But recent technological advances in autonomy and uninhabited aircraft design offer still other solutions. Assessments conducted by the Air Force, Mitchell Institute, and others suggest a new generation of autonomous drones—called autonomous collaborative platforms or “ACPs”—offer a potentially lower-cost option to provide sufficient airpower to the region, fight through attacks, and distribute U.S. force posture to confound any enemy. As Maj. Gen. R. Scott Jobe, the director of plans, programs, and requirements at Air Combat Command said in December, the introduction of low-cost ACPs into the force structure “actually changes the way we fight.”

ACPs and Force Structure

Over the past year, the Mitchell Institute worked with Air Force, industry, and DoD experts to examine the cost, capability, and capacity requirements for these drones and the impact they might have on the ability of forces to continue generating combat power while under attack. The centerpiece of the effort was a three-day workshop in which some 40 Air Force, industry, and Defense Department experts explored how China’s force posture, the geography of the Indo-Pacific, the state of advanced technology, and the U.S. budgetary environment—among other factors—might influence the design, manufacturing, posturing, employment, and sustainment of autonomous drones in a U.S. effort to assist Taiwan to repel an invasion from mainland China.

We found that ACPs could play a central role in denial, cost imposition, and resilience—the three cornerstones of the current U.S. deterrence approach, as outlined in the 2022 National Defense Strategy. In other words, ACPs can provide a way for Admiral Aquilino to get that survivable airpower into theater to bolster INDOPACOM’s deterrence posture.

During the workshop, we asked experts to identify how ACPs might mitigate current gaps in the U.S. Air Force’s ability to conduct three types of penetrating strike missions, which are critical for denying China and Russia the ability to rapidly seize territory. During these missions, advanced bombers launched major strikes against three types of Chinese military targets: a surface action group acting as a blocking force northwest of Taiwan; two mobile ballistic missile launch sites on mainland China; and an H-6 bomber base also on mainland China.

Experts assessed that the ACPs would increase the survivability of advanced bombers, increasing the likelihood that a denial campaign to blunt and halt Chinese invasion forces could succeed. Experts also concluded that ACPs could enhance U.S. force resiliency—the ability to fight through an attack, survive, and continue generating combat power—and potentially impose costs on the adversary by making it more expensive to shoot down the ACPs than to manufacture replacements.

Three Autonomous Platform Missions

Supporting Deterrence by Denial

Three critical aspects of a denial campaign are finding the enemy, generating combat power, and rapidly reducing the adversary’s warfighting capability. These would prove difficult in a race against time to prevent China’s air and maritime forces from establishing lodgments on Taiwan. Advanced inhabited fighters and bombers with low-observability and other stealth characteristics would be essential to such a campaign, because they can rapidly bring firepower to bear at scale, and they have a better chance of surviving adversary attacks to complete their mission. But with too few of them, those that are available may be stretched so thin that commanders have no choice but to employ them for “dull, dirty, and dangerous” missions, some of which may sub-optimize the use of sophisticated inhabited aircraft capabilities and aircrews and expose those aircrews to additional risk.

In the workshop, experts could draw on an extensive array of current Air Force weapon systems for their penetrating strike packages, but they often turned to advanced bombers, drawn by their survivability, range, and payload capacity. A key assumption of the scenario was that space assets had been degraded or denied; experts did have options to employ non-survivable aircraft, but assessed that China’s integrated air defense system would force those aircraft to operate only at standoff ranges, beyond the threat range.

Lacking alternatives, experts tasked bomber crews with long, dangerous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions, such as hunting for mobile ballistic missile launchers. They worried about exposing their strike packages to air defenses, a problem made more acute by the lack of advanced fighters with the range to provide offensive counterair functions, including escort and suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD), over the vast distances of the Indo-Pacific. These shortfalls led participants to rate the risk of mission failure as significant to high.

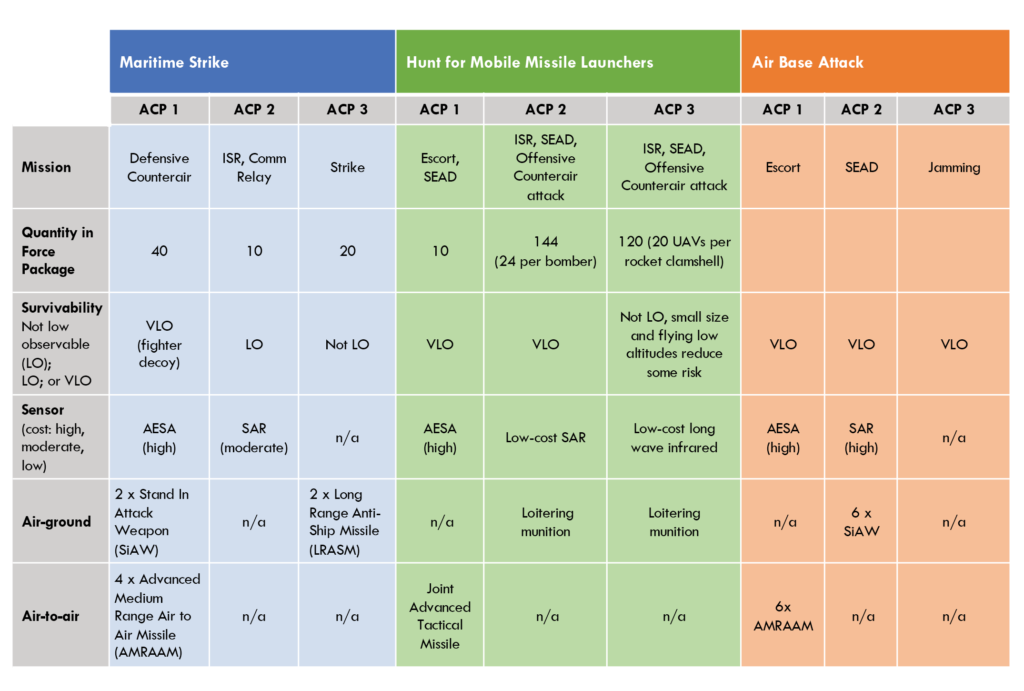

However, when experts introduced their own notional ACP designs to mitigate these shortfalls, they assessed that the risk of mission failure was much lower. As depicted in the table above, experts preferred ACP designs and force packages that distributed mission capabilities across large numbers of ACPs, as opposed to concentrating them on a smaller number of very capable inhabited aircraft. Such an approach increased mission package resiliency to losses, presented the adversary with a more complex air defense challenge, and helped reduce individual ACP costs. Larger numbers of ACPs also meant that mission commanders had more options and could therefore present more dilemmas to adversaries.

From a mission perspective, the experts prioritized the employment of ACPs to fill mission gaps. As a natural result, counterair was a top priority: six out of the nine ACP types were assigned a counterair role. Experts also focused on incorporating ISR capabilities into their ACPs, particularly for suppressing air defenses and attacking mobile missile launchers—missions that could require extensive loiter time and increased exposure to adversary threats.

Yet in assessing ACP performance, the experts were not just interested in their design attributes; the cost of the ACP was also viewed as a key performance parameter, which had to be addressed upfront, during the aircraft design phase. This thinking upends decades of acquisition culture and processes that prioritize optimizing aircraft capabilities over controlling cost. The radical mindset change was made possible because experts saw the characteristics of low-cost solutions—shorter service life and fewer capabilities, for example—as features, rather than drawbacks of an uninhabited system. In their view, lower costs reduced the barriers to taking operational risks, which in turn created new ways of fighting envisioned by Maj. Gen. Jobe in his remarks.

Imposing Costs

Experts saw the introduction of low-cost ACPs as a means to raise the price of aggression for China, while at the same time holding down the cost to the U.S. Large numbers of ACPs could confuse the adversary, acting as “missile sinks” that might force China to expend precious munitions. The net effect would be increase in bomber survivability because so many low-cost ACPs, rather than bombers, would absorb adversary fires.

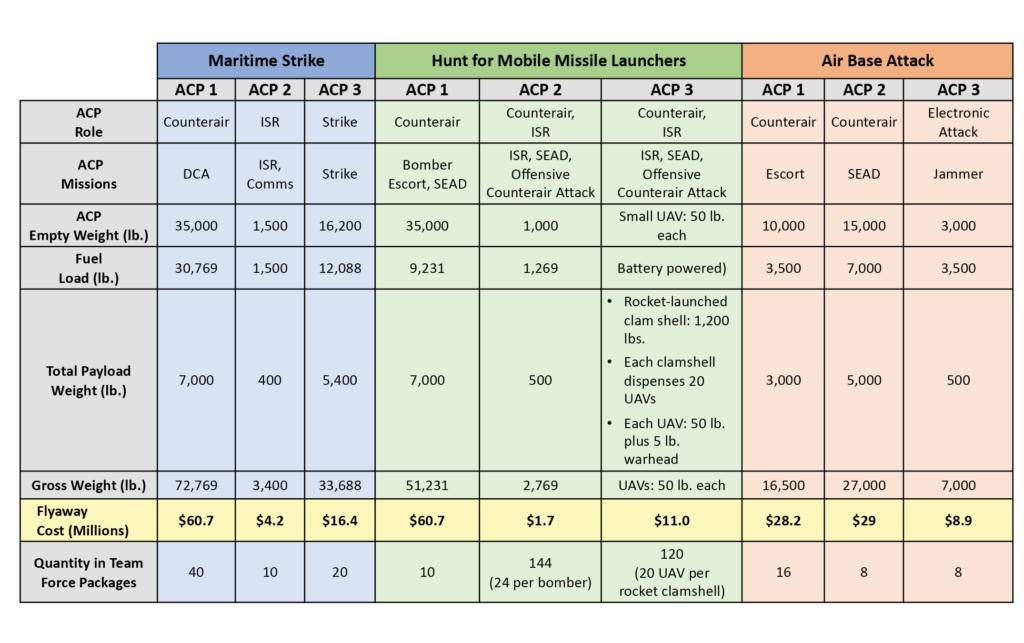

Indeed, cost-imposing advantages would accrue, experts argued, even if the cost of the ACP was not less than that of a Chinese missile or weapon system. Take, for example, China’s HQ-9 air defense system, which fires eight missiles. Experts conceived of a notional loitering munition (the mobile missile hunt team’s “ACP 2” in the table below), which could be launched in a package of 24 from a bomber to target air defenses or ballistic missile launchers. They estimated each of their ACP 2 loitering munitions would cost about $1.7 million, well greater than an HQ-9 missile, estimated at about $1 million. Assuming a 0.9 kill ratio, an HQ-9 battery’s eight missiles could destroy almost a third (7.2) of the U.S. bombers’ 24 loitering munitions, at a cost of just $8 million to China and $12.2 million to the U.S. military.

Yet even though the cost exchange favored China, workshop participants viewed it as a bargain. That’s because about 16 loitering munitions would have survived the air defense attack and gone on to destroy the $120 million HQ-9 launchers. And even if they didn’t, the ACPs would have protected the advanced bomber, a far more precious asset. Of course, as the cost of ACPs rise, the Air Force’s ability to buy very large numbers of them could decline unless additional funds could be found. But such extra costs might be well worth it. Providing protection to highly capable resources could be even more valuable in a protracted conflict, providing an asymmetric advantage against an increasingly exhausted adversary.

This point becomes particularly important as one looks at the range of estimated flyaway costs for ACP concepts produced in the workshop. Many were not as cheap as the loitering munitions. The counterair ACPs (ACP #1 across all three teams) stand out as costing much more because of their larger size, a requirement to accommodate sensors, and air-to-air payloads. Yet workshop participants still favored these concepts because they saw them as contributing to the survivability of advanced bombers.

Of course, both the U.S. and China would likely continue to adjust tactics and technology to gain an edge in this exchange. But if the U.S. were able to produce ACPs in large numbers (by either capitalizing on their relatively low cost, receiving a significant budget increase, or some combination of the two) quantity might take on a quality all its own. Gen. Charles Q. Brown, the Air Force Chief of Staff, has said that a war between the U.S. and China could see levels of combat attrition more akin to World War II than recent conflicts. Given two adversaries with rough technological parity, minimizing attrition of aircrews and aircraft could become a critical offsetting advantage—particularly in a protracted conflict. This is when operational resiliency—the ability to sustain and generate combat power while under persistent and dynamic attack—becomes key. Mass, of course, is a key aspect of resiliency. But so is the ability to disperse—a fundamental tenet of the Air Force’s Agile Combat Employment concept, which seeks to rapidly disperse forces from main operating bases to confuse adversary targeting.

Managing Costs and Missions

Improving Operational Resiliency

From a posture perspective, workshop participants recognized the vulnerability of air bases in the Indo-Pacific to potential air and missile attacks from China. Yet they also were reluctant to base ACPs outside the theater—in fact, none of them did—because doing so increased the cost of the ACPs by requiring greater range and fuel requirements, which in turn would increase the size and weight of the ACP. Because aircraft costs are calculated by the pound, more weight means more cost. Further, basing ACPs far from the area of operations would also significantly increase aircraft turn time, reducing the mass available in theater at any given time.

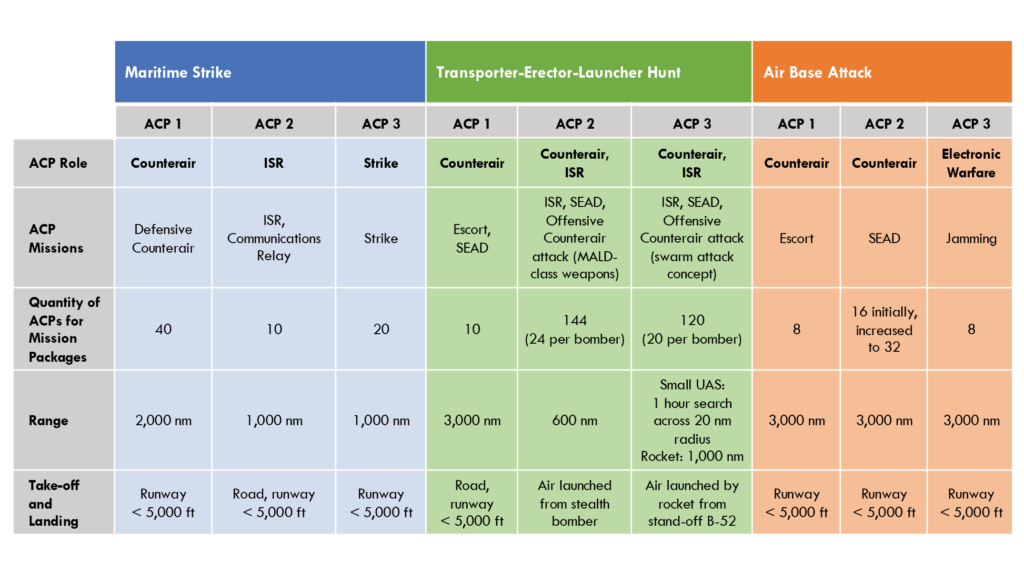

Thus, rather than opting for long-range ACPs, the experts based short-range ACPs closer to China, but with a twist: as depicted in the table above, they favored air launches, shorter civilian runways, and even dirt roads over conventional runways. These choices lend themselves to a more survivable, distributed force posture, consistent with the Air Force’s vision for ACE.

Experts acknowledged that moving off runways would, of course, present many challenges to operations, logistics, and sustainment. Launching large numbers of uninhabited systems from nontraditional areas would impose its own workforce requirements for security, maintenance, and operations. Experts worried that insufficient attention was being paid to these areas, and emphasized the need to rapidly field ACP prototypes to combat units so that some of these issues could be worked out. As such, the central recommendation emerging from our Mitchell Institute study is that the Air Force should develop a full-scale campaign of “operational experimentation” for its ACP efforts. The goal of this campaign would be 1) bolster deterrence and assure allies by deploying ACPs to combat units in the Indo-Pacific and Europe as fast as possible, and 2) asking combat units to continue experimenting with the ACP technology to better define use cases, tactics, and technology improvements required to meet operational demands.

Making Choices, Reducing Risk

A Campaign of Operational Experimentation

Our work at Mitchell Institute suggests that ACPs could offer an innovative, affordable means for the Air Force to contribute to support key tenets of U.S. deterrence: denial, resilience, and cost imposition. Large numbers of low-cost ACPs could not mitigate, but also could confound China’s A2/AD strategy—provided they can be fielded quickly.

To deliver this kind of leverage, however, the Air Force must move fast. It must build on the momentum generated by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall when he announced that building next-generation drones would be one of his top priorities. In the Mitchell workshop, experts repeatedly warned that many of the technologies they most prized in their ACPs—such as “swarm-like” collaborative autonomy—were not yet ready for “prime time.” At the same time, they worried that without new drone technologies, their strike packages would come up short against China.

One way to thread this needle is to pursue a broader campaign of “operational experimentation,” as Brig. Gen. Dale R. White, the Air Force leader responsible for development, procurement, and fielding of next-generation drones, explained at a December Mitchell Institute event. Operational experimentation involves integrating new technologies into combat units with the expectation that the technology can and will be updated to meet operator needs, changes in the threat environment, and new technology breakthroughs.

An Air Force campaign of operational experimentation could involve three crucial steps.

Proliferate Operational Experimentation Units. The Air Force’s new Task Force 99, based at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, is currently experimenting with UAVs, autonomy, and other technologies in the Middle East. Replicating Task Force 99 in both the Indo-Pacific and in Europe, the other centers of gravity for U.S. military planning, could provide opportunities to rapidly demonstrate new U.S. capabilities to allies and adversaries, alike. If fully staffed with pilots, data scientists, coders, intel operators, and acquisition specialists, these task forces could fuel rapid ACP software and hardware changes, testing and reviewing the results, and iterating improvements. The payoff would be the proliferation of state-of-the-art ACPs into other combat squadrons. By using these task forces as testbeds for thinking about how to organize, train, and equip combat units, they can lead the way in developing new tactics, techniques, and procedures that can be rolled out to the wider force.

Prioritize Modularity. ACPs will need to accommodate constant software upgrades, evolving AI technology, and other mission system changes. Workshop participants saw ACPs enhancing combat effectiveness only when the ACP could operate with a high degree of independence from human control. Without sufficient autonomy, experts worried it would be difficult for the Air Force to scale its ACP fleet without over-tasking aircrews and slowing down the decision cycle. Even though such sophisticated autonomy may not be available today, the modularity it requires must be built in from the beginning to accommodate it when it does arrive. From a cost perspective, workshop participants noted that modularity and “open architecture” designs would allow the Air Force to maintain the same air vehicles while changing out the software to accommodate different mission sets. This would be important, since the Air Force sees ACPs contributing to a variety of mission areas, including air dominance, reconnaissance, strike, mobility, and training.

Build Coalitions. The third aspect of an operational experimentation campaign involves building an effective coalition. Experts at the Mitchell workshop widely agreed that the Air Force has come far in the past year in articulating the use cases for ACPs and communicating with industry and Congress. But as Air Force leadership seeks significant resources for ACPs in the President’s 2024 budget request, it must articulate the case to all the relevant stakeholders in order to gain buy-in. The Air Force should develop an ACP flight plan that links the technology to the deterrence approaches outlined in the National Defense Strategy and lays out both aggressive timelines and the need for agility, so that programs can shift as changes in technology and the threat environment evolve. The Air Force could also consider hosting unclassified wargames with lawmakers, staffs, and industry, to allow stakeholders to see what ACPs can bring to the fight.

The Air Force must also regularly engage with industry, especially at the unclassified level, to align incentive structures for ACP production. The U.S. military’s traditional acquisition model—in which companies make the majority of their profits on aircraft sustainment—will not work for low-cost ACPs designed to be attritable or even expendable. The Air Force must work closely and openly with industry to figure out how to align these incentives and maximize low-cost ACP production.

Opening the Overton Window

In the 1990s, political scientist John Overton described how the range of acceptable policy preferences shifts over time through a concept called the Overton Window. Policies that were once unimaginable—in this case, the idea that combat units might operate AI-enabled drones alongside inhabited aircraft—can eventually become more mainstream as the window expands. During the Mitchell Institute workshop, we saw how advances in technology, combined with concerns about the changing threat environment, are helping to create the case for expanding the window to include the deployment of ACPs. At the same time, a new wave of Air Force autonomy experts are writing books, leading experimentation, and pushing for competitive, open and flexible acquisition strategies—all steps that advance the case for the role of uninhabited aircraft and autonomy in deterrence and warfighting.

Solving Admiral Aquilino’s problem—a lack of aerospace capability and capacity in the Indo-Pacific theater—will require quickly turning ACP concepts into combat-capable reality. INDOPACOM, Congress, and DOD should all be paying close attention to the Air Force’s ACP plans in the President 2024 budget request. While there is no “silver bullet” solution to deter China from aggression, rapid fielding and continuous experimentation with ACPs offers an important contribution. The Air Force is ready to throw open the Overton Window; now everyone else needs to get onboard.