In October 2022, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration Frank Calvelli released his nine “tenets” of space acquisition, meant to guide the future of the Space Force’s capabilities. His very first step: Build smaller satellites.

Nearly two years later, the service has made some progress in embracing so-called “small sats,” but there is still plenty to do—and possible ways to use small satellites that at least publicly the Space Force has not taken, according to a new report from the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Retired Space Force Col. Charles S. Galbreath, a senior fellow at Mitchell, and Aidan Poling, a research analyst, co-authored the 25-page policy paper, which was released July 25 and has more than half a dozen recommendations for the Pentagon to fully embrace small satellites.

“There’s obviously a lot of interests in small sats, but it’s primarily focused on small sats for resilience and in low-Earth orbit,” Galbreath told reporters. “… But the truth is small satellites can provide a lot of utility beyond just proliferation, beyond just the deterrent aspects and disaggregation. So we wanted to explore how they can be used support all three elements of competitive endurance and help achieve space superiority.”

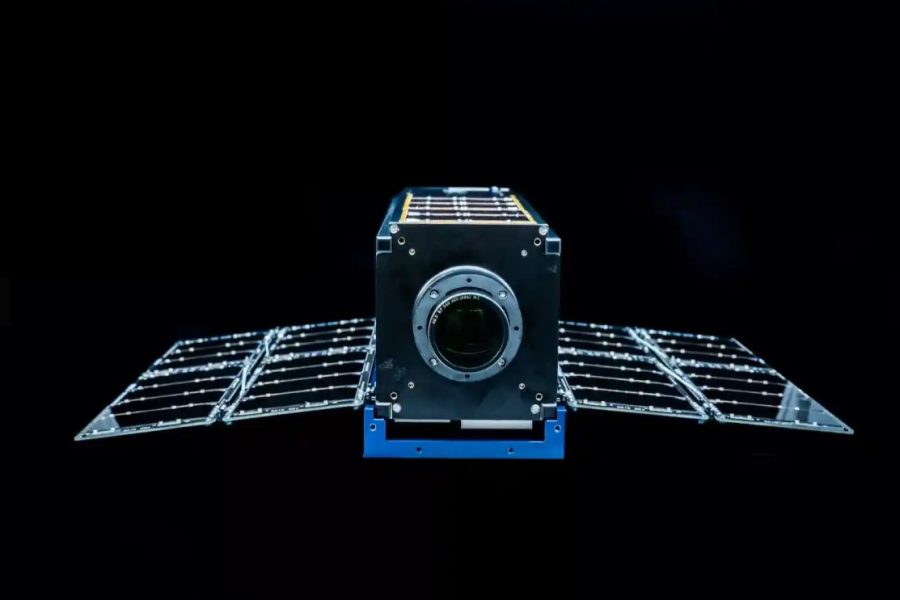

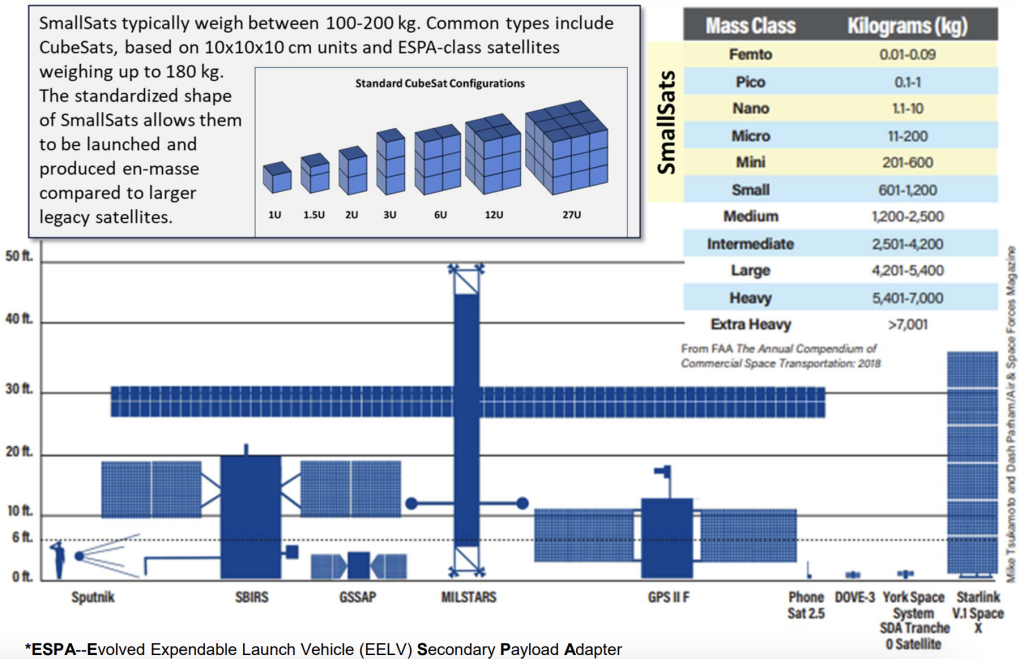

Small sats include any satellites under 1,200 kilograms. Within the Space Force, perhaps the most well-known example is the Space Development Agency’s Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, which features hundreds of satellites “about the size of a loaf of bread,” Galbreath said, a fraction the size of legacy satellites that can sometimes be as large as a bus.

Yet while SDA has been hailed as a success story and implemented many of Calvelli’s acquisition tenants, Galbreath argued more can be done—both with acquisitions and operations.

New Orbits, New Roles

While the very first satellites in space were small, a confluence of factors steadily drove the U.S. to build bigger and bigger satellites over the years, such as:

- Strategic mission sets that required low risk, requiring redundancy for assurance

- Bulkier, larger technology

- Longer development timelines

- High launch costs forcing officials to maximize every opportunity

In recent years, proliferated low-Earth orbit constellations of small satellites have experienced a surge in interest, led by SpaceX’s Starlink. Yet Galbreath and Poling argue the conditions are right to expand the use of small satellites across the board:

- New missions like moving target indication and tactical communications

- Miniaturized technology

- “Spiral” development with rapid updates

- Lower launch costs and lower risk

“Calvelli has talked about using small satellites, not just in LEO, but in all orbital regimes,” Galbreath said. “And I think that absolutely has to be part of architecture going forward. We’ve seen small satellites and even cubesats out to cislunar. And so the utility of small sats that 10 years ago, wouldn’t have been possible is now operationally relevant.”

And while SDA is primarily focusing on data communications and missile warning/missile tracking for its small sats, Galbreath also believes the potential is there to explore new uses for them.

“Small ‘bodyguard’ satellites with non-debris generating kinetic or non-kinetic effects could be stationed next to high-value satellites to protect them from attack,” Galbreath and Poling wrote.

The Space Force could also deploy small sats as “co-orbital weapons to disable adversary satellites using localized kinetic, EW, lazing, spoofing, or jamming techniques,” they wrote. “These ‘hunter-killer’ SmallSats could patrol near adversary assets, hide in less monitored orbits, or remain with a larger bus or an upper-stage vehicle waiting for activation.”

The Space Force has expressed interest in refueling satellites in the future—“hunter killer” small sats could be refueled by their “motherships” to extend their lives, Galbreath said.

Such concepts echo ideas from other military services, like fighter escorts or Collaborative Combat Aircraft from the Air Force or aircraft launching from a carrier from the Navy, Galbreath and Poling said. But to make them happen, the Space Force has to develop its own tactics, techniques, and procedures, especially for operators to handle large numbers or clusters of satellites all at one time, they recommended.

Addressing Threats

Small satellites don’t just help counter adversary threats by introducing more and more targets for them to consider, the analysts argue. They can be released in clusters, more easily hide in different orbits, and even take advantage of camouflage, concealment, and deception techniques.

“When SpaceX launched Starlink, the astronomy community really raised concern about the impact that was having on their ability to collect data,” Galbreath noted. “And so SpaceX began a campaign to add in non-reflective materials, as well as light-absorbing paints that help reduce the signature. And so we could apply the same sorts of techniques to our small satellites.”

Proliferation remains a powerful advantage as well, especially if spread across orbits, they wrote. Even Russia’s plans to develop a nuclear weapon to go in low-Earth orbit, which could take out hundreds of satellites indiscriminately, show the value of small sats, Galbreath argued.

“Small sats create an incredible opportunity for us to recover from that in a rapid fashion, through rapid development, mass production, and then able to use a variety of launch providers, including heavy launch or even small launch, to replenish or reconstitute lost capabilities,” he said. “Additionally, when we’re talking about where small satellites can be used, it’s not just LEO, it’s all orbital domains. And if Russia is going to put a nuke in every orbital domain, I think we’re going to be in a whole different type of conflict.”

Finally, Galbreath and Poling also advocated for more “single purpose” satellites to make it even harder for an adversary to knock out a broad swath of capabilities.

Culture Change

While Calvelli has emphasized proliferation and small sats and some parts of the Space Force are pursuing them, Galbreath argued a broader mindset shift is needed to fully embrace them. That starts with larger “block buys” of satellites that will encourage manufacturers to create production lines of satellite buses, a far cry from the exquisite, hand-crafted satellites of years past.

“How can the Space Force better utilize all of the potential of small satellites?” he said. “It’s going to require shifting our mindset, shifting our policies, and our acquisition approaches, as well as enabling the industrial base to make that adjustment and shift.”

Industry seems to already be taking notice.

“There’s the traditional industry and how they’re beginning to pivot towards small sats. But there’s also the development of sort of a cottage industry around small sats, where companies are focused, that is their primary product line,” Galbreath said.

But in order for the Space Force to fully make the pivot, it will require more money, he added, which is in short supply at the moment. The service is looking at its first ever budget cut in fiscal 2025.