When the revived U.S. Space Command got up and running more than one year ago, Pentagon leaders knew they needed the group again, but how would it work?

The organization, which manages operations of the satellites, radars, and other support systems that enable everything from guided missiles to troop communications, launched in August 2019. The Space Force was created shortly after to provide personnel and resources to that command for daily combat needs.

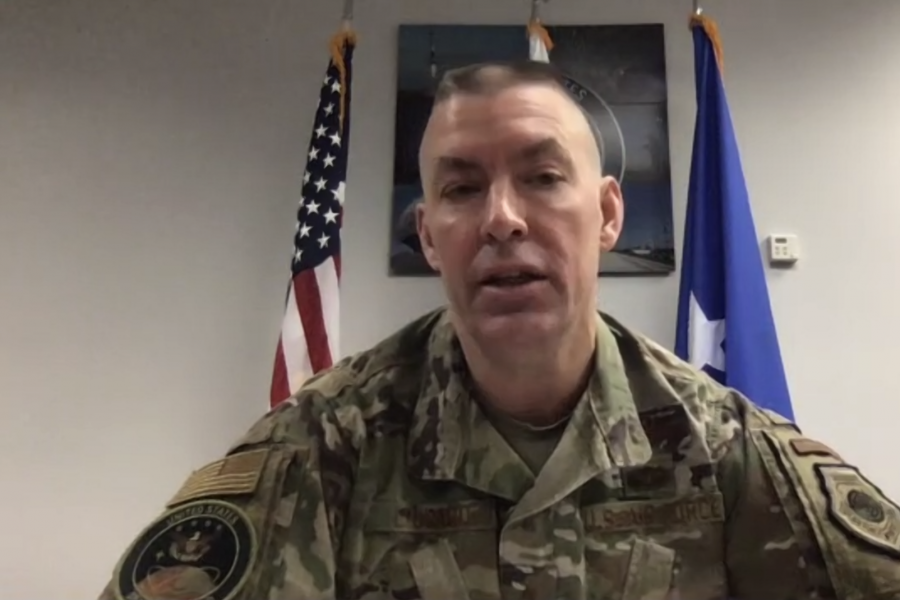

Since then, SPACECOM has built a staff of nearly 600 employees from across the military, according to Chief of Staff Brig. Gen. Brook J. Leonard. It currently plans to grow to nearly 1,400 personnel, first based at the temporary headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base, Colo. The Pentagon is considering six locations, including Peterson, to become the permanent HQ.

SPACECOM hopes to draw from a robust local military, civilian, and contractor workforce that offers space and joint warfighting expertise, Leonard said Dec. 21 at an event hosted by the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. About 60 percent of the command’s headquarters will be civilian employees.

“We are able to do what the nation needs us to do, but to stay ahead of our enemies, we’re going to need to continue to build out,” Leonard said. He noted the armed forces will be fairly evenly represented across that workforce.

Eighty percent of the command’s time and resources will be spent on short-term planning and operations, while the other 20 percent will be focused on research and development for big, futuristic ideas.

What has matured so far is the command’s understanding of how the armed forces should work together to use and defend space assets. The Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Space Force each have a component at SPACECOM that are experts in how the services rely on space, and the Air Force is exploring its options as well.

“This traditional way of looking at warfare, where you have these phases that you incrementally ratchet up through and you finally get to, ‘Hey, bullets are flying now,’ that’s really not the way it’s going to play out,” Leonard said. “The timing of that is going to be different across the domains and the dimensions of the conflict or of the competition that you’re in.”

A scuffle in space could lead to further aggression on Earth, he added: “We might need to go first in space, we might need to be able to survive and take a punch in space.”

Rather than rely on traditional bombing and ground combat campaigns, they’re drawing up new concepts of how to strategically “set the battlespace” to compete for global influence with countries like Russia and China.

In their thinking, space and cyber forces should partner with “gray forces,” like undersea or special operations troops, for targeted offense and defense, Leonard said. Successful operations could lead to smaller-scale conflict that stays more in the digital realm than the physical.

“How do we think about the fact that competition and staying in the game, and doing so in a way that we can easily pivot, but yet at the same time, show strength, is key to winning without fighting?” he added.

Those considerations are still evolving. China’s mining enterprise on the moon is expanding the scope of how SPACECOM defines its future responsibilities, Leonard said: “That forces us to be able to think through how we would secure that environment for the Artemis program, as we go back to the moon as well.”

Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk’s aspirations to colonize Mars is also shaping those plans, since the U.S. military plans to support commercial companies as they head farther away from Earth.

“What’s the outer boundary of our area of responsibility?” Leonard said. “I mentioned 100 kilometers is sort of the inner boundary, but what’s the outer boundary, and how fast are they going there, and in what way are they going there?”

Global—and extraterrestrial—planning calls for close ties with the other combatant commands. SPACECOM this year has worked to fully staff its planning cells that liaise with the other COCOMs, and already has those teams in place at U.S. Strategic Command, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, and U.S. European Command.

“We have some future missions that we’re preparing for: our global satellite communications manager mission and our global sensor mission, and how that plays into missile warning and missile defense,” Leonard said. “We’re working very closely with [U.S. Northern Command], as well as Strategic Command to be able to do that right, and really make the most efficient use out of many of our sensors that do a lot of the same things.”

In particular, Leonard noted the partnership between space and U.S. Cyber Command personnel is key. If those networks are attacked, space systems could be little more than hardware floating on orbit.

He added the growing relationship between the Space Force and the Intelligence Community is leading to a resurgence in operations intel that helps U.S. troops understand how space systems are designed and how an adversary might wield them.

“We’re starting to stitch together our processes and our capabilities,” Leonard said. “It’s been wonderful to see the expertise that they bring to the field, but also the reliance that they have on space—in particular, operations intelligence, which had subsided in the 17 years where Space Command was not in existence.”