United Launch Alliance, America’s longtime space launch provider, recently cut ties with one of its suppliers amid worries that the company’s Chinese owner could steal sensitive information.

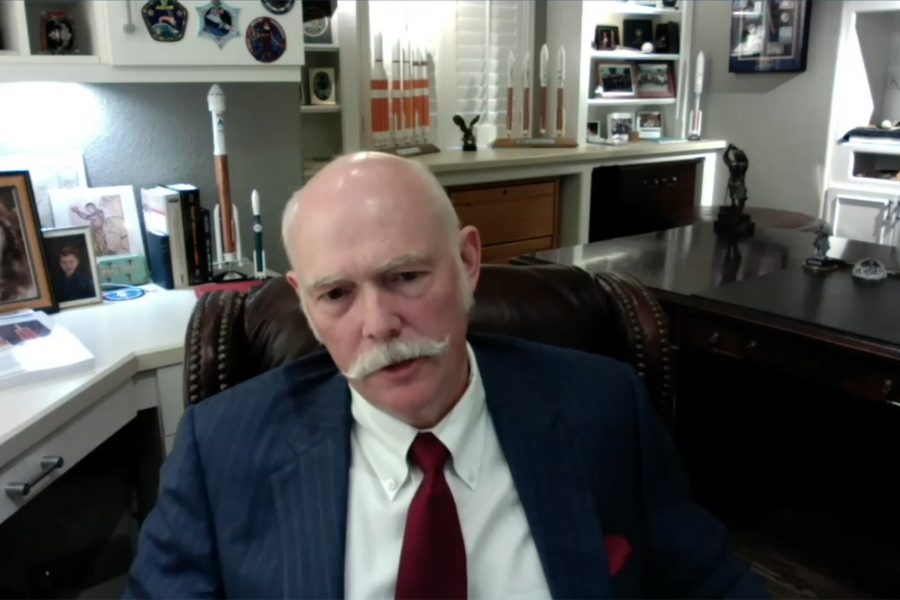

ULA Chief Executive Officer Tory Bruno discussed his “wake-up call” that the Chinese could access proprietary data in a Sept. 15 conversation with Space Force Vice Commander Lt. Gen. David D. Thompson during AFA’s virtual Air, Space & Cyber Conference.

Kuka, the Germany-based robotics firm acquired by China’s Midea Group in 2017, provided ULA with tooling software that helps manufacture rockets like the future Vulcan Centaur. That rocket recently landed ULA the job of carrying payloads to orbit on 60 percent of Space Force launches through 2024.

“Just a few months ago, maybe a year ago now,” Bruno said, “We discovered almost by accident that the key element in that software chain, a key company, had been purchased by a company owned in China. When we followed up with the FBI and the counterintelligence activity that they provide … we realized, yeah, this is not an actor we need to have inside our factory.”

ULA spokesperson Jessica Rye told Air Force Magazine the company first contacted its major tool supplier that worked with Kuka as well as Kuka directly. ULA determined its robot tool programming was handled exclusively by a U.S. supplier.

“There was no evidence of access to our systems or compromise” of ULA’s intellectual property, Rye said. She did not answer when asked when ULA became aware of the issue, but said it “envisions no further future work involving Kuka or Kuka products.”

A Kuka spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

The incident spooked Bruno, who said ULA—a joint venture between defense giants Lockheed Martin and Boeing—couldn’t afford to wait for the U.S. government to tell it what to do.

“We went out and put an architecture together. First thing is to go to the supply chain and ask them to certify their ownership. Are you a domestic company or not? Who are your shareholders?” Bruno said. “For those of you who are not up to snuff, you’ve got to fix it. If you can’t fix it, we’re going to replace you. If we can’t replace you, we’re going to have to figure out how to break up the work into little bitty pieces so you don’t know what you’re working on, and you’re not getting access to our intellectual property.”

ULA hired the business analytics firm Dun & Bradstreet to ferret out suppliers who have foreign backing through shell companies, indirect ownership, and other means.

“I have to do that literally every quarter,” Bruno said. “This is a really dynamic environment.”

Rye said ULA hasn’t found any direct Chinese ownership of other companies in its supply chain.

Even as the Pentagon has crafted new policies to protect defense suppliers, repeatedly warning of information breaches and tainted products, Bruno wants the government to lend a hand in finding potentially bad actors. He suggested Congress should take up legislation that makes it harder for China to acquire U.S. companies or invest in supply chains affecting American products.

“Even when they’re not buying the company, when you think you’re in Silicon Valley with venture capitalists getting investment into startups or into new technologies, when you tunnel through those guys, you find out there’s a lot of Chinese money in San Francisco,” Bruno said. “That is how they get access and influence in that chain. All of that’s got to be made legally much more difficult, so that it’s easier for everyone to act.”