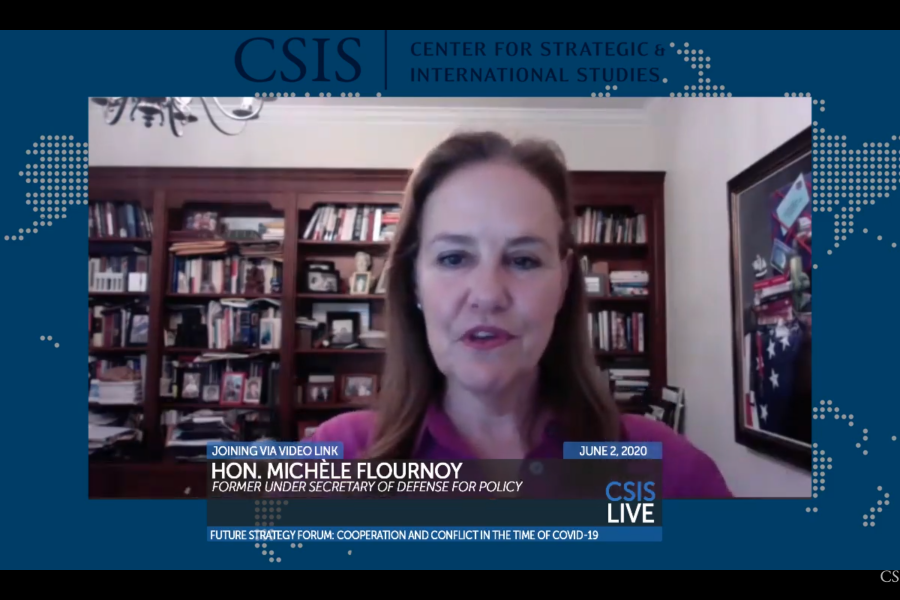

The United States’ reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic is feeding partners’ and allies’ fears that the U.S. “is no longer willing to play a leadership role” amid international crises and opening the door for enemies and competitors, alike, to challenge its dedication, former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy said during the opening session of the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ third-annual Future Strategy Forum on June 2.

According to Flournoy, the nation’s hesitance to “step up and step in to orchestrate an international, collaborative response that included everyone”—as it did during the Ebola crisis—has egged on these concerns.

“What that does is, on the part of partners and allies, it creates lots of hedging behavior and lots of uncertainty because they don’t know that they can count on the U.S. to make good on its security guarantees or its promises in other areas,” she told Kathleen Hicks, CSIS’ Senior Vice President, during a livestreamed conversation. “And it sort of invites adversaries or competitors to test the limits of U.S. resolve and commitment as we’ve seen Russia do repeatedly in the Middle East, for example, or … China in the South China Sea. So it’s a really dangerous situation where we’ve created a vacuum that is sort of strengthening others with interests antithetical to our own.”

Though partners and allies had these worries before Trump’s arrival at the White House, he has “dramatically exacerbated” them, she said.

Flournoy cited the fact that the U.S. neither convened the Group of Seven nor the G20, as well as Trump’s recent disavowal of the World Health Organization, as evidence of America’s paradigm shift. And though she noted that global institutions such as the WHO and the United Nations require reform “in most cases,” she said walking away from them completely can be dangerous.

“When we walk away from these institutions and just abandon them to others, they tend to evolve in directions that are not helpful to us,” she said. “When we double down, and invest, and try to reform them from within and influence their behavior by showing up and leading, they tend to move in a much more positive direction.”

She added that rendering the WHO “inffective … will come back to bite us,” either in the context of the current coronavirus crisis or in terms of future pandemics.

Prior to the pandemic, Flournoy anticipated that Europeans and allies might do more with regards to defense in response to that proverbial vacuum and was concerned “about their hedging against … U.S. absence, because that’s not a healthy thing for a transatlantic alliance like NATO,” she explained.

But now that it’s here, she said, she worries that their leaders’ bandwidth and national spending “will be refocused on the obvious domestic and economic priorities, post-pandemic.”

“I think it just leaves us less united, less coordinated, and less effective as allies, as a democratic community,” she said.

Since the majority of the country entered quarantine in March, defense leaders have repeatedly touted U.S. readiness, warning potential adversaries that the U.S. military remains ready to counter potential threats.

The Pentagon has paraded its capabilities through massive elephant walks and large force exercises. U.S. Northern Command recently announced what it called a “first of its kind” air defense exercise aimed at protecting the homeland, which included Airmen and aircraft from four combatant commands.

“The first question a lot of people ask me from a military perspective is ‘are we ready today to handle whatever threats that we have to deal with?’” USAF Gen. John Hyten, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said during a May 21 online town hall. “And the answer is—by every measure you can have—is that we are ready for every threat that potentially we would face today in the world.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on June 2 at 10:18 p.m. EDT to correct the name of the CSIS event.