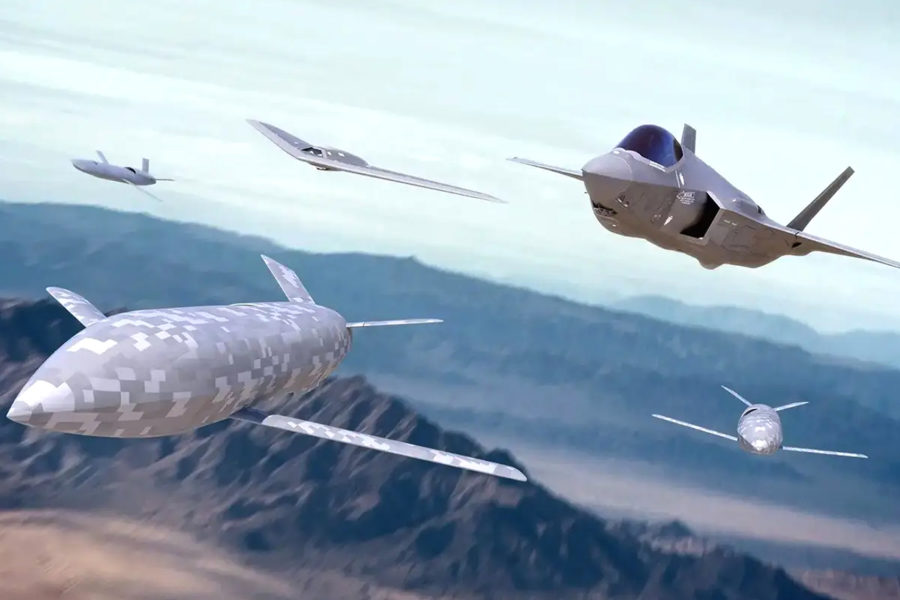

The Air Force is getting ready to award $10 million worth of study contracts for engines that could power later versions of the Collaborative Combat Aircraft, but has not yet nailed down performance specifications, service engine officials said last month. They are continuing to take the pulse of industry for innovative solutions that will meet CCA propulsion needs for the long-term.

“Our intention is to award those propulsion studies here in the near future, and then continue to refine that, find that way,” John Sneden, director of the Air Force propulsion directorate, said at the Life Cycle Industry Days conference in Dayton, Ohio, at the end of July. He didn’t specify when the awards would be made. The Air Force has not disclosed previous contract awardees for CCA elements, such as for autonomy, to maintain security.

The study tender was released July 18 and responses were due Aug. 2. It did not specify how many respondents would be picked to split the $10 million in research money.

While the contractors for the first increment of CCA—Anduril and General Atomics—have engines as part of their offerings, the Air Force continues to reach out to industry “to see what is available for the second increment,” Sneden said.

“The final requirements are still in a state of evolution,” he said. The requirements will dictate the thrust and class of engine needed, and USAF “is just going to really assess what is in the art of the possible … so we can inform the propulsion way ahead.” But he emphasized that the service is “not locked into any specific thrust class right now and trying to stay open.”

That openness corresponds to a wide playing field in industry across thrust classes, Sneden said, with many options that could conceivably provide a winning solution or be part of one.

“We’re not in a place where we’re really kicking anybody out,” he said.

The Air Force will “go through the prototype study evaluation, in the 2025 time frame, and then start … getting into next steps and their prototyping. But again, that’s all going to be a function of where the program gets taken and how much funding” is available, Sneden said.

The Air Force held an industry day in June to talk with suppliers about what they can offer for CCA propulsion.

Last year, the service released a request for information that specified engines in the 3,000-8,000 pounds of thrust class, but that shouldn’t be construed as a final requirement, Sneden said. That RFI was “basically looking at: what can the industrial base do for us?”

Moving forward, the propulsion directorate is “looking at what technology options we have at three years, at five years and seven years.” That will include prototypes and studies to consider cost, schedule, and performance.

At the Farnborough Air Show last month, GE Aerospace and Kratos Defense announced they are partnering to develop a small class of engines they believe will be applicable to CCAs. Their first such powerplant is in the 800 pounds of thrust class but could be scalable to “just under 3,000 pounds” of thrust, GE officials said. The GEK800 engine is applicable to drones, loitering missiles, cruise missiles and other small powered weapons, but could be scaled to power a CCA, they said, adding that final decisions will depend on where the Air Force finally settles as to the class of engine it wants.

“We have numerous initiatives underway” to enhance the CCA propulsion “ecosystem,” Sneden said.

“We’re continuing efforts to drive speed and options across our enterprise. That includes things like doing digital trends, having an advanced manufacturing repair ecosystem, using big data analytics to inform our maintenance and deployment activities, as well as establishing another transactional authority contract vehicle that will help expand the propulsion industrial base,” Sneden said.

He said the focus of CCA propulsion right now is on the future, and everything the directorate is doing is aimed at “driving propulsion capability options for the long-term future of CCA.”