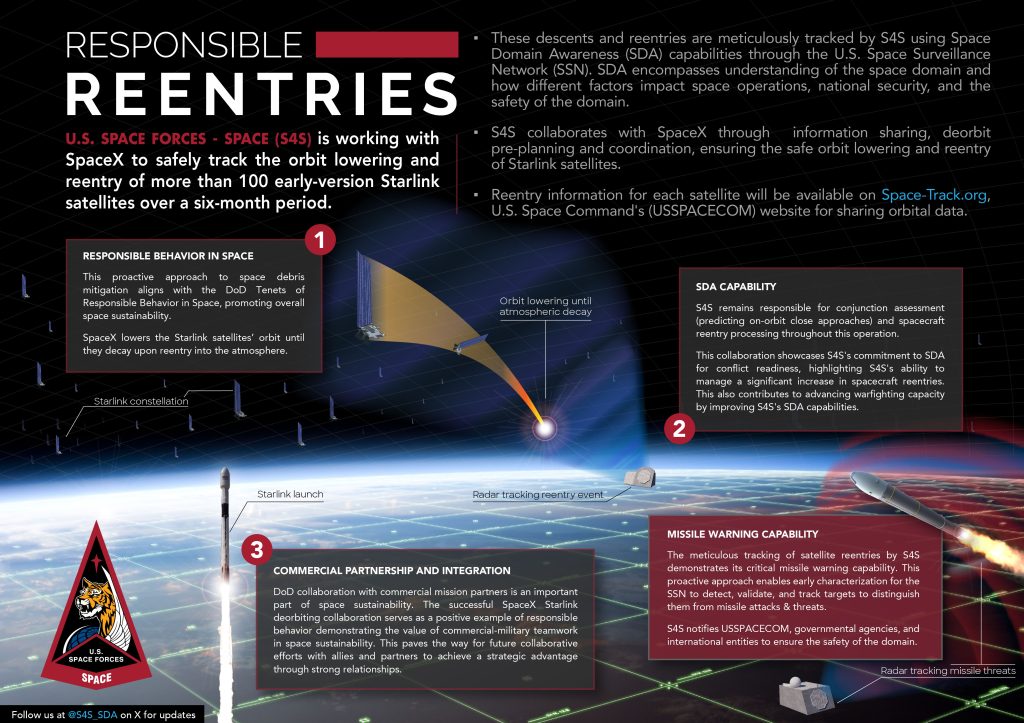

As SpaceX begins to decommission and “deorbit” 100 of its oldest Starlink satellites, the Space Force is gathering crucial data and real-world experience for Guardians.

Since May, Space Forces-Space, the Space Force unit that presents forces to U.S. Space Command, has publicised on social media the many satellites, rockets, bits of debris it’s tracking as they reenter the atmosphere. But while that work has gone on for years, the difference now is that SpaceX isn’t passively waiting for its spacecraft to decay or drop from space, but is actively pursuing their demise.

SpaceX announced in February it would initiate controlled descents for 100 of its older Starlink satellites over the span of several months, dropping them into lower orbits so the Earth’s gravity can finish the job, pulling them down into the atmosphere, where they burn up upon reentry.

The Space Force’s Space Delta 2 tracks spacecraft orbits and debris and issues warnings when there’s risk of collisions so satellite operators can maneuver to avoid them. But tracking de-orbiting satellites also gives space operators a chance to practice Space Domain Awareness with real-world events, said retired Air Force Col. Jennifer Reeves, a senior resident fellow for space studies at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

“This is an amazing opportunity for the Space Force to work with SpaceX to understand when they think everything is going to be burning back in, based on the actions that SpaceX is going to be taking to deliberately deorbit these … and then we get the immediate feedback of what the sensors on the military side are actually seeing,” Reeves said. “That validates in a very specific way what our sensors are actually seeing, that they’re actually seeing these de-orbits, and what might be different from one event to another.”

The Space Surveillance Network—a collection of ground- and space-based sensors—will track the de-orbits, offering Guardians “reps and sets” to hone their skills. “We really are at the beginning of a lot of de-orbiting and understanding what that looks like in the sensor and the reporting network of the Space Force,” Reeves said.

The expansion of so-called “mega-constellations” in space, featuring thousands of small satellites in low-Earth orbit, will necessitate de-orbiting as the satellites age. There are more than 5,000 Starlink satellites alone, and other companies are fielding or developing similar-sized constellations, as is the Space Force’s Space Development Agenc, which is planning the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, which will consist of hundreds of satellites in LEO.

The Federal Communications Commission has adopted a rule requiring commercial operators to de-orbit their satellites within five years after a satellite completes its assigned purpose—so ultimately, as many satellites as are launched into space will have to be de-orbited.

“The lessons learned out of what happens with a [proliferated] LEO constellation are going to be applicable to everybody, including the Space Force,” Reeves said.

Guardians will also be able to use deorbiting to hone missile-warning skills. That’s because, like the infrared signatures of missile launches, satellites reentering the atmosphere will also have their own haveinfrared signatures.

“As a person who’s done this for years and years as a youngster, how you actually see that on console tends to look different,” Reeves said. “However, there are instances where sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference. So more examples of things coming back” is just an ideal opportunity to practice with real-world data, rather than simulations.

“Man, talk about getting to test out not just our equipment, but to test out the eyes of our young operators,” Reeves said, and “to make sure they know what to look for and what to see. And of course, they do, but more reps is always better.”