Pentagon officials are slowly offering a clearer picture of the roles satellite and radar systems play in the joint fight, after U.S. Space Command launched anew last year as part of a massive revamp of military space resources and doctrine.

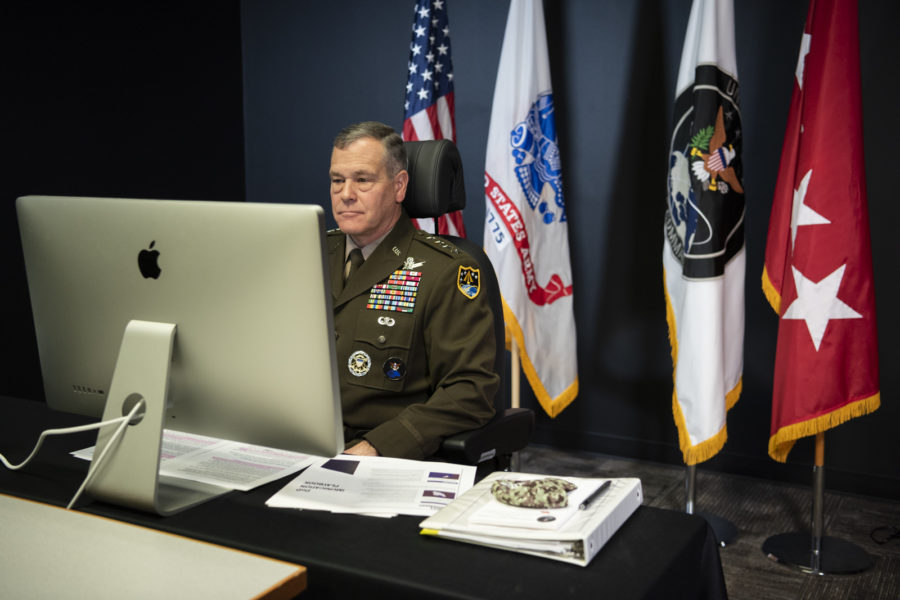

SPACECOM boss Gen. James H. Dickinson on Nov. 5 provided a peek into how the U.S. might respond to an enemy attack on the ground control systems that talk to military communications satellites, disrupting their ability to send data to troops around the world.

“This attack would have significant strategic-level consequences,” the Army four-star said during an event hosted by the Space Symposium.

Regional troops on the ground or in the air would defend those ground systems in such an event, showing that space assets not only support other parts of the military but are deserving of support themselves.

Those forces would pull information about their surroundings from intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance technology on orbit, Dickinson said.

“Our mutual … objectives would be to locate and destroy adversary forces attacking our ground segment,” he said. “The result would be our continued ability to provide space warfighting capabilities in all domains.”

The U.S. government is increasingly concerned about the vulnerability of its space assets, which led to the creation of a modern SPACECOM and the Space Force to defend them and fight back.

An earlier version of SPACECOM, which was disbanded in 2002, was different from the new organization because it did not play the same dual roles of supporting other combatant commands while being supported itself, Dickinson said.

A scenario like that described by Dickinson could come into play during any conflict where an adversary group or country wants to gain the upper hand over American troops.

Dickinson offered another anecdote about the value of space in military operations. Space and cyber forces came together to aid ground troops as the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq tried to oust Islamic State militants from their de facto capital city of Raqqa.

“They had collected pattern-of-life information on [the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria], including communications nodes, primary and secondary and tertiary fallback locations,” Dickinson said. “At mission go time, our soldiers used space-enabled capabilities to identify and then disrupt and deny those ISIS touchpoints.”

U.S. troops used the data they received through surveillance to move to their advantage “across multiple domains,” Dickinson said.

Space assets lent insight to cyber operators who worked to make it easier for the coalition to travel on the ground. The U.S. and its partners took advantage of knowing where militants would go and the communications tools they would rely on to carry out a cohesive plan of movement and attack.

“It all gave us physical, temporal, positional, and psychological advantages, leading to mission success,” Dickinson said. “It was this kind of cross-domain synergy that led to the recognition of the need to establish space and cyber as distinct warfighting domains.”

The Space Force has also discussed instances in which satellites have contributed to the safety of U.S. troops. Space-Based Infrared System satellites controlled by the 2nd Space Warning Squadron at Buckley Air Force Base, Colo., detected more than a dozen Iranian missiles fired at American and coalition forces in Iraq in January.

“Those missiles flew for six minutes,” Space Force Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David D. Thompson said in February. A U.S. Central Command official told him: “If those Airmen on crew that night, specifically the warning officer at the warning station, if she had not done her job better than her training, … today we would be talking about dead Americans at [al-Asad Air Base].”