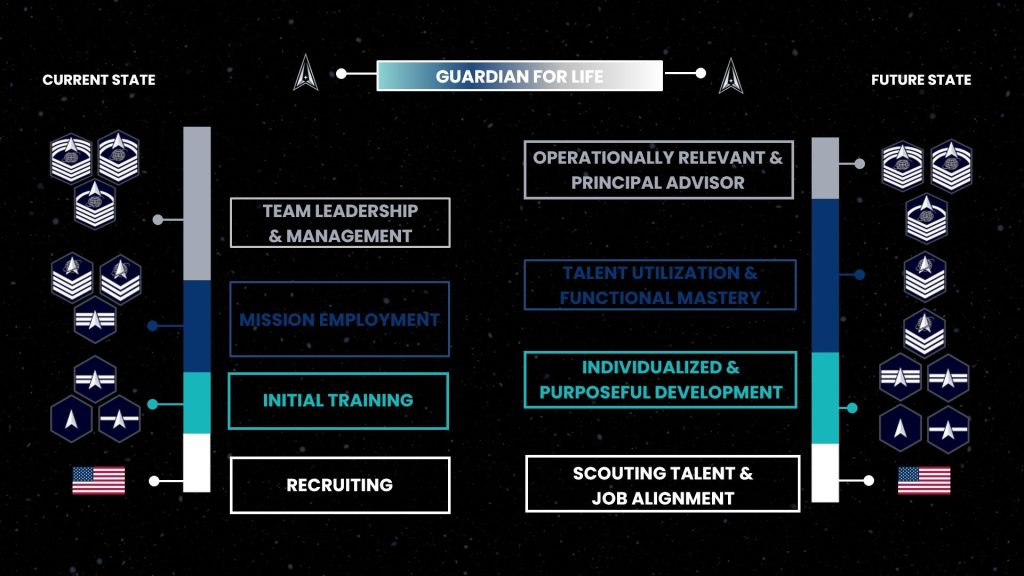

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—The Space Force’s top enlisted leader unveiled an ambitious project to transform the career paths for the service’s 4,900 enlisted Guardians. The new “Vision for the Enlisted Force: Development Path” aims to make each Guardian’s training experience more meaningful and to better prepare them for the increased responsibility they will face in the branch’s unique force structure.

“We have today, at the five-year point of the service, to make the decisions and set the conditions for the success of Guardians 20 years from now,” Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force John F. Bentivegna told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

The new model is part of a larger plan to transform the entire Guardian experience, which Bentivegna hopes to achieve through three key initiatives: improving the quality of life and service for Guardians and their families; optimizing training, development, and talent management; and investing in the legacy of the service so that Guardians feel connected even after they hang up the uniform.

“I want to make sure that your experience is one that you value, one that you respect, one that you brag about when you talk to your friends and your neighbors and your family,” Bentivegna said Sept. 17 at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference. “That’s why I envision the Guardian experience. That’s why these are my key initiatives.”

Recruiting

Before enlisted Guardians ever get near basic military training, the process begins with recruiting. Today, the Air Force Recruiting Service recruits for the Space Force, but it must do that at two vastly different scales: AFRS will bring in roughly 27,000 enlisted Airmen across 130 job specialties this fiscal year, compared to just 700 new Guardians in three job categories for the Space Force.

The partnership is working well so far, but Bentivegna sees the potential for change.

“They’re doing a phenomenal job and I have no complaints about the Guardians that are being recruited today,” Bentivegna said. “It’s just doing so in a model that’s not optimized for what we need, or it doesn’t embrace the opportunities that we could leverage because of who we are and the size that we are.”

The Space Force is creating a detachment within AFRS to build a strategy for taking on the recruiting mission, Bentivegna said last month. Bentivegna also hopes to refine the service’s initial assessments of recruits. The Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), the military’s standard entrance exam, does not capture with enough granularity whether a candidate is best suited for a particular career field, he said.

“It doesn’t really give me a measurement of success to say, ‘based on the assessments we’ve done, I really think you’d be really good at intel,’ or ‘I really think you’d be good at cyber.’” the chief explained. “The fidelity just isn’t there yet.”

Beyond specific skill sets, Bentivegna also hopes to test potential recruits for character and grit, personality traits he believes can be as important as technical skills for a Space Force career.

“I don’t want to disenfranchise anyone who has the grit and character to be a Guardian, but maybe they didn’t go to a high school that offered advanced placement courses,” he said. “I want to be able to cast a wide net and encourage individuals from all walks of life, and I can teach them orbital mechanics, I can teach them math and science.”

Booting Up

The project would also refine initial skills training, where Bentivegna hopes a Guardian’s performance will have a more direct impact on their early career. For example, the Space Force assigns new Guardians based on which tech school they just graduated from, but does not necessarily factor in whether the Guardian performed particularly well in a specific kind of intelligence, for example.

A future model would continually assess Guardians’ strengths and interests, which could affect their first operational assignment and level of responsibility coming out of tech school. While the needs of the service come first, USSF’s compact size enables more flexibility for placing Guardians where they can make the most meaningful impact. The chief compared it to how college students can choose focus areas, elective courses, or minors within their degree field.

“Did they show strengths and interest in orbital warfare for space superiority, or in advanced research of capabilities that some of our adversaries may be developing,” he said. “I want to structure these courses so that they’re meaningful: They understand as they go through it, it’s going to have a direct impact on their career opportunities and career progression.”

Likewise, trainees who show higher levels of maturity and aptitude might expect more responsibility and opportunity “as you prove yourself to the institution through these transparent and equitable processes,” he said. But the chief cautioned against using the word “promotion,” which he believes has a more competitive connotation than the term “career advancement.”

“It’s not about competition amongst Guardians,” he said. “It’s about individualized accomplishments and progression in their own individual career.”

Bentivegna also hopes to weave the space domain into a Guardian’s tech school experience. Currently, cyber and intelligence enlisted Airmen and Guardians go to the same tech schools, where much of the concepts and philosophy focus on winning in the air domain.

“In the future, we want it to be space-minded-specific domain training that they’re getting in the tech schools,” he said.

The Space Force is considering splitting off its own tech schools, though that option is still being evaluated, Bentivegna said. In August, Bentivegna also announced a new Noncommissioned Officer Academy tailored to the Space Force. USSF is also developing course programming for officers, launching its first Officer Training Course this month, a one-year, full-time program for all newly-commissioned officers.

“There are things long-term where we will have a relationship with the Air Force, but there are things as a service that we need to do on our own,” the chief said in his keynote address.

Combat Leaders

Unique among the military branches, the Space Force’s officer-to-enlisted ratio is nearly 1:1, with some operations leaning more enlisted-heavy, Bentivegna said. That suggests different requirements for senior enlisted experts, he said, anticipating that “there is going to be a need for master sergeants specifically to do more tactical leadership with increased responsibility … doing the day-to-day mission in our combat squadrons.”

The model is a change from today’s construct where senior noncommissioned officers are responsible for a smaller share of day-to-day responsibilities.

“A lot of times today our senior noncommissioned officers, our master sergeants, get through their technical sweet spot and right away we’re pushing them to do management and backshop activities,” Bentivegna explained. “I don’t think that’s where we need to be in the future.”

Changing that may require more flexibility in how assignments are distributed.

“It’s less about ‘I need a sergeant, here’s a sergeant who’s up for an assignment,’” he said. “It’s more about individualized talent management specifically informed by the Guardian and the needs of the service.”

Under the future model, Guardians can expect to stay hands-on even as they rise to the highest enlisted ranks. Bentivegna recalled trying to get into meetings as an E-9 only to be told “you don’t need to go to that meeting because this is not like, management stuff, this is operational stuff,” he said. “You don’t have the clearances, you don’t need to know what’s going on operationally.

“That’s a complete pivot where we’re going: where our senior leaders are going to be just as responsible for the readiness and training and execution of operations as their teammates,” he added. “When I talk about the future, I want to really hammer home the expectation that you never lose that requirement to be operationally relevant.”

Getting There

The project marks the Space Force’s latest effort to balance mission readiness, quality of life, and personal fulfillment, a balance which it holds at the core of its identity. Other initiatives include a part-time Guardian force, continuous fitness tracking, and distinct new uniforms.

But actually implementing these changes takes time, with some Guardians citing the term “semper soon,” a riff on the branch’s motto “semper supra.”

Bentivegna acknowledged that achieving this new vision for the lifecycle of enlisted Guardians could take years. For now, he and his team are still figuring out what policies, programs, or even legislation may need to change and what stakeholders need to be involved. As chief enlisted leader, Bentivegna has the power to provide guidance, influence, and intent, but not to execute policy decisions.

Still, the chief said the project is necessary for the Space Force to be ready for the future. The project comes at the end of a busy 18 months which saw the service reissue its mission statement, stand up new units called integrated mission deltas and integrated system deltas, and redefine its operating theory, called competitive endurance. The changes have been “evolutionary” for the service, he said, which drove his vision for the enlisted force. That, and questions from senior service leaders asking how to develop the force of the future.

“It will take many evolutions, many steps, years, to fully implement this,” Bentivegna said. “But if we don’t invest in the future today, we’re never going to get there.”