Technological innovations like laser communications links between satellites are driving new capabilities for American warfighters, but the real game-changing disruptions come when new technologies converge with each other, U.S. Space Force acquisition officials told an industry conference on Dec. 7.

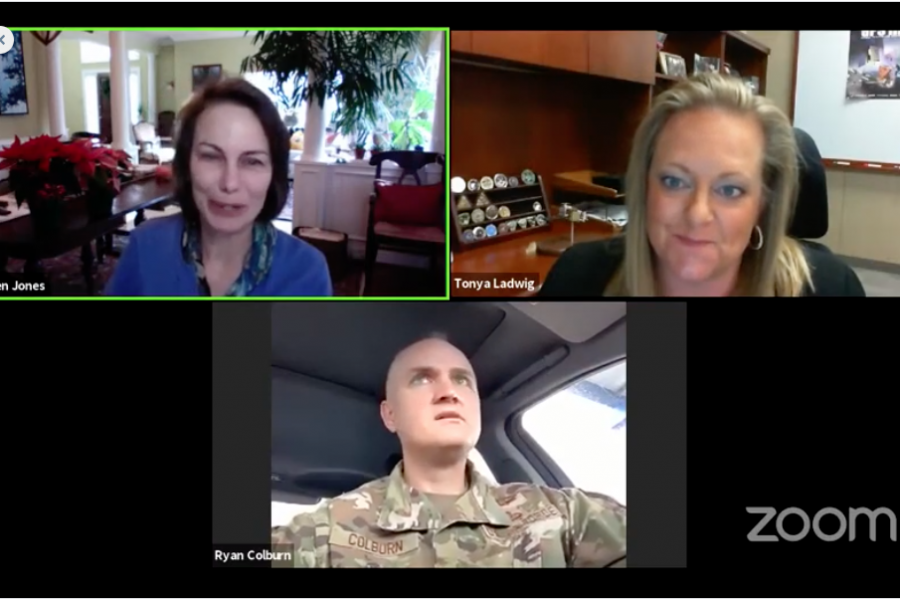

“When I converge capabilities, that’s when I’m disruptive,” Col. Ryan Colburn, director of the Spectrum Warfare Division of the Space and Missile Systems Center, told the opening panel session of MilSatCom Digital Week.

He offered three new technological advances as examples:

- Optical cross-links: Near-instantaneous, laser-based communications between satellites in a constellation

- On-orbit reprogramming: Software-defined satellites that give operators the ability to upgrade satellite capabilities by updating software after its been deployed to space

- Smaller, lighter and more powerful antennas and a distributed ground system for forces on the ground.

“Our challenge is to combine those [new] capabilities in a flexible and linked architecture,” said Colburn, as the Space Development Agency will do with its planned low Earth orbit constellation of small satellites known as the transport layer.

But as panel moderator Karen Jones of the Aerospace Corporation think tank noted, only one of those three advances—the advent of software-defined satellites—is completely novel. Both smaller antenna and optical cross-links are incremental improvements to what is already deployed on many satellite constellations.

It is the combination of those new capabilities together that creates a game-changing new capability, Colburn argued.

Optical cross links will eliminate the latency created when satellites can only exchange data via the ground system. Software-defined satellites will enable the constellation to be launched in waves, each one more advanced than the last, but all upgradeable with the latest programming. And smaller, lighter antennas on the ground mean that an increasing number of weapons systems and other tactical equipment can be equipped to receive data and even instructions

Derek M. Tournear, director of the Space Development Agency, explained how that convergence would be enabled for the transport layer by standards-based, open, modular architecture, enabling multiple vendors to build satellites that work as part of the constellation.

Tournear, the first-ever director of the new agency, is seen by many as the architect and driving force behind the extraordinary speed with which SDA is moving. Stood up in March 2019, the agency plans to conduct its first launches in 2022—breakneck speed for military space acquisitions, which traditionally takes a decade or more to get into orbit.

The agency will be buying new waves of satellites to add to the transport layer every two years after that, in what Tournear called “spiral development”—each spiral more advanced than, but still compatible with, the last. An open modular architecture is essential. “We need to ensure that not only can one spiral talk to the future generations, … but we want to have multiple providers all talk amongst themselves,” he added

SDA had defined a cross-link standard, he said, though “it wasn’t a standard that SDA came up with. It was a standard that basically industry said, ‘This is what we all can meet.’”

Having a single standard that every vendor bidding must meet, Tournear added, means “now I can have a complete constellation made up of different sets of satellites, all made by different manufacturers, but they function together as one cohesive unit.”