A new unit activated recently at Peterson Space Force Base, Colo., is the branch’s first-ever targeting squadron, designed to scope out adversary space capabilities and present options to the joint force on how to neutralize them.

“Today is a monumental time in the history of our service,” Lt. Col. Travis Anderson, commander of the 75th Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Squadron, said in a press release about its Aug. 11 activation. “The idea of this unit began four years ago on paper and has probably been in the minds of several U.S. Air Force intelligence officers even longer.”

Space systems are made up of three elements: the satellite, the ground station that commands and controls it, and the signal that connects the two, retired Space Force Col. Charles Galbreath, senior resident fellow for space studies at the Mitchell Institute, told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

“My interpretation of space targeting is understanding all of those elements for an adversary system and then being able to make recommendations on what would be the best way to counteract that threat system,” he said. “In some cases, that may mean sending a jamming signal from our Counter Communications System, or it could mean putting a JDAM on a building somewhere to destroy the command and control or the end user.”

The 75th ISRS is part of Space Delta 7, the operational intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) component of the Space Force. While its sister squadrons also perform ISR and likely have targeting elements, the 75th consolidates targeting expertise and acts as a focal point for stakeholders who need that information, Galbreath said.

Before the Space Force launched in December 2019, Air Force intelligence officers often served just a single assignment in space, which precluded a robust corps of experts in the field, he said. The 75th is likely one of several new stand-ups to occur in the near future as the Space Force develops ranks of specialized experts.

“Having a squadron like this creates an opportunity for true depths of understanding of the threat environment,” he said.

Assessing space systems can be a difficult task. For example, dual-use satellites may present a challenge for intelligence officers trying to assess threats—China may claim that a robotic arm attached to a satellite is intended for space debris removal, but it could also be used to grab and disrupt other satellites.

Air Force space operators-turned commercial space executives expressed a similar concern during a panel discussion hosted by the Hudson Institute in July.

“Commercial operators become targets when they support the DOD,” Even Rogers, former Air Force space operator and CEO of the space technology company True Anomaly, said at the discussion. “In fact, I suspect that there are some incentives that would cause commercial operators to be targeted first as a strategic off-ramp in a broader conflict, because it is a gray zone, there is uncertainty about whether the United States intends to defend and protect … commercial providers.”

Other challenges include locating a satellite and its ground station, and determining what information its crew needs to operate and where its orders come from. Working together, the 75th ISRS and other intelligence organizations can fuse “a consolidated picture of what makes an adversary threat system tick, and therefore how can we best defeat it?” Galbreath said.

As adversary space capabilities become more sophisticated, so too must U.S. counterspace capabilities. Future operators may need to use cyber or electromagnetic spectrum weapons to target enemy satellites, especially when ground stations are tucked away behind an anti-access/area-denial environment such as mainland China. The problem is that the U.S. does not have many counterspace weapons at its disposal, especially compared to its main rival.

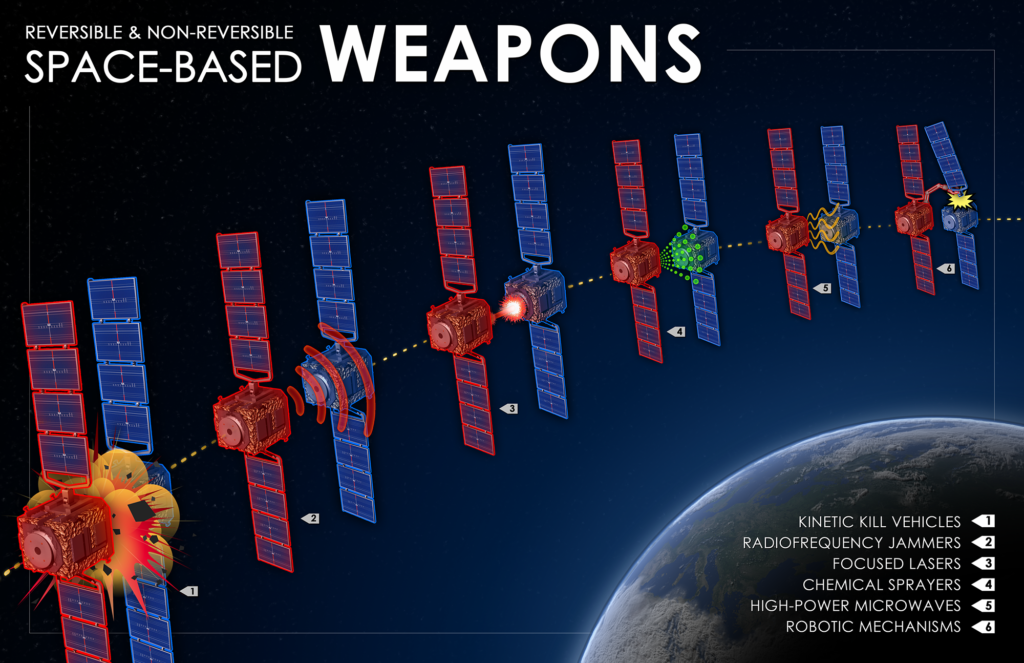

“China has already fielded an alarming array of operational counterspace weaponry” including ground-launched kinetic weapons and lasers, cyber capabilities, and electronic warfare weapons, Galbreath wrote in a June paper on counterspace capabilities. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army is also developing space weapons that could attack with robotic arms, electronic warfare, or lasers.

The U.S. defense against such weapons must include establishing international norms of behavior in space, resilient space system architecture that can withstand attack, and exceptional space domain awareness, Galbreath said. But it must also include strong counterspace capabilities.

“The United States has largely shunned the thought of fielding space weapons since the end of the Cold War,” the retired colonel wrote. “However, recognizing space as a warfighting domain means any serious effort to achieve space security must include space weapons.”

At least one such system is on the way. In April, Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman promised Congress a “substantial on-orbit capability … in full spectrum operations” by 2026, though he did not provide many details on what that capability might look like. Galbreath argued that the U.S. needs an architecture of multiple new counterspace systems to protect its space enterprise.

In the meantime, the 75th ISRS will analyze existing threats and how to counter them—the latest addition to the “mighty watchful eye” lauded in the Space Force official song.