OKLAHOMA CITY—Within a brand-new, gleaming-white facility called the “high bay” at the Oklahoma City Air Logistics Complex, a battered and rusty-looking fuselage and left wing of a B-52H has become a laboratory for the government-industry team that will revamp the aged Stratofortress fleet for the next 30 years.

Still bearing its nose art—nicknamed “Damage, Inc. II”—the B-52H, which sat in the “Boneyard” at Davis-Monthan Air Force, Ariz., for more than two decades, will serve as a testbed for engineers looking to align new digital models of the bomber with the hands-on real world.

The right wing and tail horizontal stabilizer from the aircraft are in a separate stress test facility—McFarland Research and Development in Wichita, Kan.—to determine how much structural life is left in the wings and control surfaces of the B-52 fleet, among other things.

The carcass will be a valuable tool for engineers “who have never had the chance to get inside” one of the bombers, said Jennifer Wong, head of bomber programs for Boeing, which along with Rolls-Royce provided travel, meals, and lodging for reporters traveling to Oklahoma City to report on the B-52J program.

Boeing is responsible for integrating the various upgrades that will turn the B-52H into the B-52J, including new engines, a new radar, communications and navigation, new weapons, and other improvements.

“In order to perform all of the necessary mods of this program, we are touching more than just the engines,” Wong said.

The carcass will allow engineers to crawl around in the airplane, to see how much space there is for installation of new gear and for maintainers to work on new equipment, and to appreciate the variations present in an aircraft built with sheet metal methods and blueprints more than a half century ago, Wong said. And crucially, it will allow these explorations without taking any of the Air Force’s current B-52s out of commission.

The aircraft made the month-long, 1,500-mile flatbed journey from Davis-Monthan to Oklahoma City in early 2022 and is already serving as a reality check on the B-52 engineers’ digital models, used to project how they will mount new engines and pylons, run new cable, replace cockpit instrumentation, and otherwise organize the B-52’s rebirth.

The carcass has also helped engineers determine the proper placement of the B-52’s new Rolls-Royce F130-200 engines, to see how the flaps will have to be re-shaped to accommodate the new engine nacelles. It will also offer an opportunity for fit-tests of new cockpit displays, wiring, and generator accessories that will be located in the landing gear bays, for example.

The digital models are intended to make sure those new items don’t interfere with older ones; the carcass ensures the models haven’t missed something, such as “finding out you can’t reach a particular panel once this new thing is in place,” one engineer said.

“We like to say everything underneath the wing is pretty much brand new … or modified for this program,” Wong said. “But in doing so, when you integrate new engines, you’re also affecting the wiring … the hydraulic system, the power system. … All of those have to be redesigned, modified and/or developed.”

The hope is the B-52 carcass will smooth the way toward final designs.

The virtual reality systems developed by Rolls-Royce and Boeing for the new engines and other aircraft gear have gotten high marks from maintainers and will likely be offered to the Air Force as a maintenance training system at some point, company officials said. But that is not part of the B-52 upgrade effort, according to Col. Louis Ruscetta, senior material leader for the program.

“This is an upgrade with a lot of moving parts,” Ruscetta said. “I want to keep this … as simple as possible.”

For example, installing the new radar and preventing it from interfering with other systems is a formidable task in itself. It comes in two parts: the sensor of the AN/APG-79V4 used on the F/A-18 will be in the new radome, but the processor will come from the APG-82 flown on the F-15. They will be mounted—together—and must fit in fuselage space occupied by the current system.

The new system is also heavier than the old one, and though it doesn’t affect the aircraft’s weight and balance, the structure in that part of the aircraft has to bear a new load.

The radar will be used for both targeting and navigation but won’t be integrated with the electronic warfare system, Ruscetta said.

“We have that as a growth requirement,” he said. “It will have the hooks to do that. But under the KISS methodology [Keep It Simple, Stupid], I wanted to make this a radar integration program, and not an EW integration program, which is a lot different scope.”

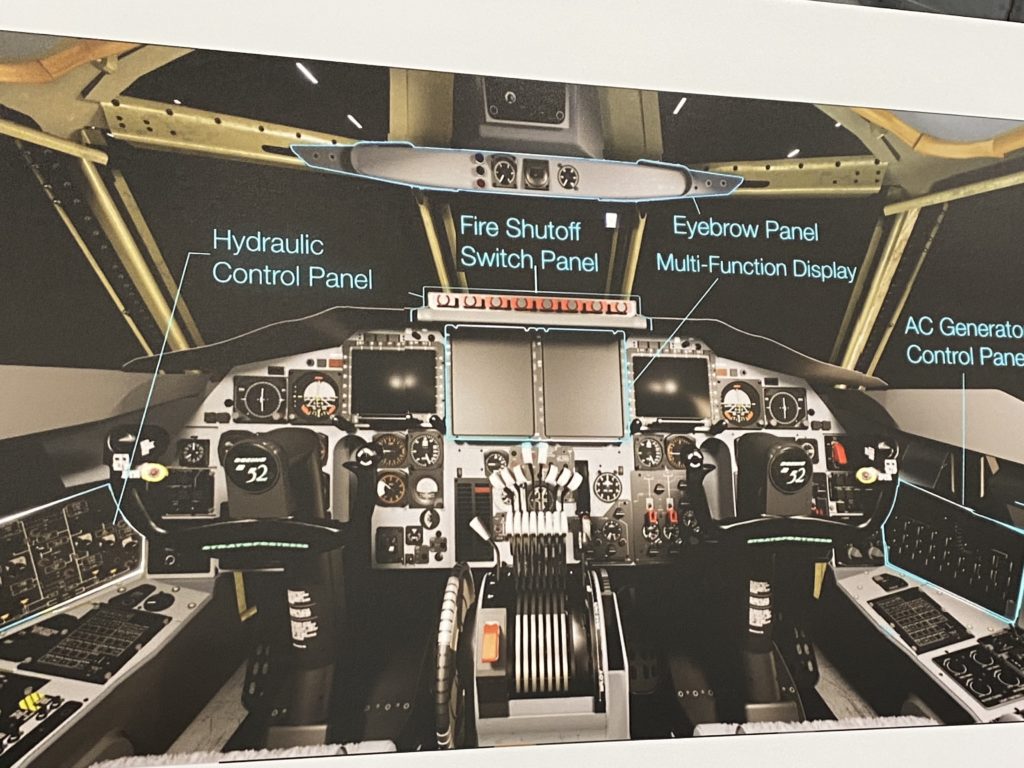

In the cockpit, the digital models can be checked to see if crewmembers can see and reach new displays and controls associated with the new systems or upgraded to new standards. Because the B-52 was built in the 1960s—from a 1950s design—not all sizes of Airmen will be able to operate the aircraft, but the program is aiming to make the cockpit friendly to more pilots.

The High Bay will also serve to test interfaces for various weapons, pylons, and other B-52 accessories. Present in the facility were two dummy rounds of the AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), several variants of the GBU-31/32/38 Joint Direct Attack Munition, the ADM-160 Miniature Air-Launched Decoy, B-52 wing-mounted weapons pylons, a Common Strategic Rotary Launcher, and various items of B-52 ground equipment. There also appeared to be other weapons which a Boeing official said might be future “notional” munitions.

One aspect of the B-52 not getting a refresh is its basic appearance. While the C-5M Galaxy got fresh interior paint and soft surfaces when it was re-engined in the 2010s—Air Mobility Command generals said they wanted their Galaxy pilots to feel like it was a new airplane—the B-52 won’t be getting any such cosmetic improvements.

“That’s not part of this program,” Ruscetta said, though the Air Force might opt to do it at some later date.