U.S. Strategic Command is conducting an “exhaustive assessment” of current global threats, as adversaries like Russia and China force the U.S. to rethink the way it approaches strategic deterrence.

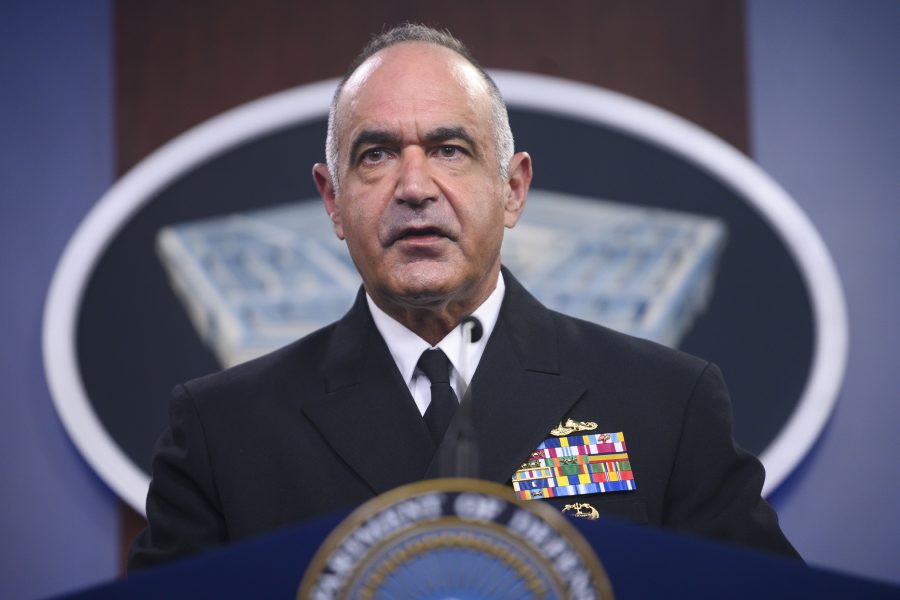

“I’ve challenged my command to revise our 21st-century strategic deterrence theory that considers our adversaries’ decision calculus and behaviors, and identifies threat indicators or conditions that could indicate potential actions,” U.S. Strategic Command boss Adm. Charles “Chas” A. Richard said in a pre-recorded speech for the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ two-day, virtual nuclear security conference, which began Oct. 21.

The analysis will include a look at emerging capabilities, changing norms, and potentially unintended consequences of conflict, as Pentagon officials argue other world powers have “blurred the lines” when it comes to conventional and nuclear conflict. That could be a challenge for the U.S. military, which tends to organize, train, and equip its forces based on whether their mission is nuclear-related or not.

That shift in thinking is driven by a push toward so-called “tactical” nuclear weapons, which Russia and the U.S. are both deploying as tools in a regional conflict that would complicate an adversary’s decisions without escalating into all-out nuclear war. Opponents say that view is misguided.

In August, then-Air Force deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration Lt. Gen. Richard M. Clark said the service has started to shape policy around the concept of “conventional and nuclear integration,” viewing them as two points on a spectrum instead of as separate concepts.

“We have to be able to reconstitute our capability. We have to be able to plan and execute integrated operations, multidomain, whether conventional or nuclear, and most importantly, we have to be able to fight in, around, and through that environment to achieve our objectives,” Clark said.

Richard argues the ultimate goal—ensuring that the benefit of restraint outweighs the benefit of possible action—has not changed. However, “we have to account for the possibility of conflict leading to conditions that could seemingly very rapidly drive an adversary to consider nuclear use as their least-bad option,” he said.

By the end of the decade, the U.S. will for the first time face two nuclear-capable competitors, each of whom must be deterred differently.

He estimated Russia is “close to 75 percent complete” with its aggressive nuclear modernization efforts, as well as conventional advancements, ensuring it is still very much a “pacing threat.”

“Russia has expanded the number of circumstances under which they would consider the employment of a nuclear weapon, or at least they’re now willing to say it publicly,” Richard said. “Although this circumstance is distressing, it should not come as a surprise.”

China also is a growing threat, Richard said, cautioning the audience not to undermine its capabilities or nuclear ambition. He believes they will match America’s nuclear strength by 2030.

“They always go faster than we think they will, and we must pay attention to what they do and not necessarily what they say,” he said.

China’s investment in “sophisticated” command and control capabilities and ongoing efforts to build up its own nuclear triad seem to contradict its claim that deterrence should require as small of an arsenal as possible, Richard said.

The United States is pointing to those countries and others like North Korea and Iran to argue for the continued modernization of America’s nuclear missiles, bombers, and submarines, slated to cost more than $1 trillion.

“I recognize that great power competition doesn’t equal conflict, or that we’re on a path to war, but as the commander in charge of employing strategic deterrence capabilities for the nation, and our allies, I simply don’t have the luxury of assuming a crisis, conflict, or war won’t happen,” Richard said.