As Pentagon and Space Force leaders plan for future dynamic space operations where satellites can maneuver as needed and get refueled to prolong their service lives, industry leaders are preparing to deploy new technology and finalizing their concepts of operations for what they agree is an “incredibly hard mission area.”

Refueling Interfaces

In-orbit refueling requires some kind of port or interface for satellites to receive fuel. Industry officials compared such a port to the “inlet of a gas tank” or a “gas cap” on a car. The Pentagon has extensive requirements for such receptacles for aerial refueling, but standards for a satellite equivalent are still being hashed out.

On Jan. 29, Northrop Grumman announced that Space Systems Command had selected its Passive Refueling Module (PRM) as a “preferred refueling solution interface standard.” Lauren Smith, Northrop’s program manager for in-space refueling, told Air & Space Forces Magazine that the module went through a “rigorous review” with SSC’s engineering review board and is the only interface to receive that certification to date.

“Standards are important to help the entire satellite service ecosystem grow, and we want to do the right thing for our customers,” Smith said. “There’s a demand signal that preparing satellites for refueling is important moving forward. And since the PRM has been identified as an SSC preferred refueling solution, the approved version of the PRM documentation and specifications will be provided by SSC.”

The plan is to have the PRM flying on satellites in orbit by 2025, Smith added.

Yet an SSC official later told SpaceNews that the selection did not mean the Space Force would use the PRM interface exclusively. And an executive with Orbit Fab, a startup that has developed its own port called the Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface (RAFTI), told Air & Space Forces Magazine that its interface will go on Space Force satellites too.

“We have eight RAFTI refueling ports currently going to [Air Force Research Laboratory] and Tetra-5 missions in the short term, and many more headed for spacecraft programs around the world this year and beyond,” chief commercial officer Adam Harris said. “RAFTI is shipping to SSC spacecraft this month.”

Smith said Northrop will retain the intellectual property rights to the PRM, but the government, which helped fund the technology’s development, will have usage rights and can distribute the technical specifications to other contractors, who will not have to pay a licensing fee. Harris said RAFTI “is available for $30,000 to anyone that wants refueling.”

Getting the Gas to the Customer

Between RAFTI and PRM, more refuelable satellites will likely launch in the coming years.

Actually doing the refueling is another story—and Northrop and Orbit Fab are taking different approaches.

Orbit Fab’s plan is to have operational fuel depots, or what it calls “Gas Stations in Space,” in the next few years. But the depots themselves won’t refuel satellites. Instead, they will stay in place and “shuttles” will maneuver between the two so that the client (such as the Space Force) doesn’t have to burn fuel getting to the depot.

In late January, Orbit Fab announced it was partnering with another startup focused on in-orbit servicing, ClearSpace, to collaborate on operations and key technologies.

“You can think of ClearSpace as kind of being the tow truck in space. So we do a number of different servicing capabilities, whether it’s hauling you off the side of the road, or it’s topping off your fuel tank,” Tim Maclay, ClearSpace’s U.S. general manager, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “Eventually we’ll be replacing batteries and doing maintenance and that sort of thing. So we’re really sort of the AAA of the satellite world. And so with regard to refueling, think of us really as the last-mile delivery between the fuel depot and the customer.”

Orbit Fab is also working with Astroscale, another startup, on a Space Force project called the Astroscale Prototype Servicer for Refueling (APS-R) that is scheduled to go into orbit in 2026. In January, Astroscale revealed new details on the project, including a concept of operations for how it would use the RAFTI interface and dock with an Orbit Fab depot.

Partnering with other companies to get fuel to client satellites “is the fastest way to get our service to market,” Orbit Fab CEO Daniel Faber told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Such speed is important, he added, because the Space Force is pushing industry to provide in-orbit refueling on an accelerated timeline.

“The government is now trying to move our timelines to the left,” Faber said. “They’re pushing really hard to make this happen quicker. The generals are saying every single spacecraft should be refuelable from, well, they started by saying the end of the decade, now they’re saying 2028. We’re going to get operational by 2026 and then give them that confidence that it’s going to work and that they can get these things installed and then they’ll get refueled.”

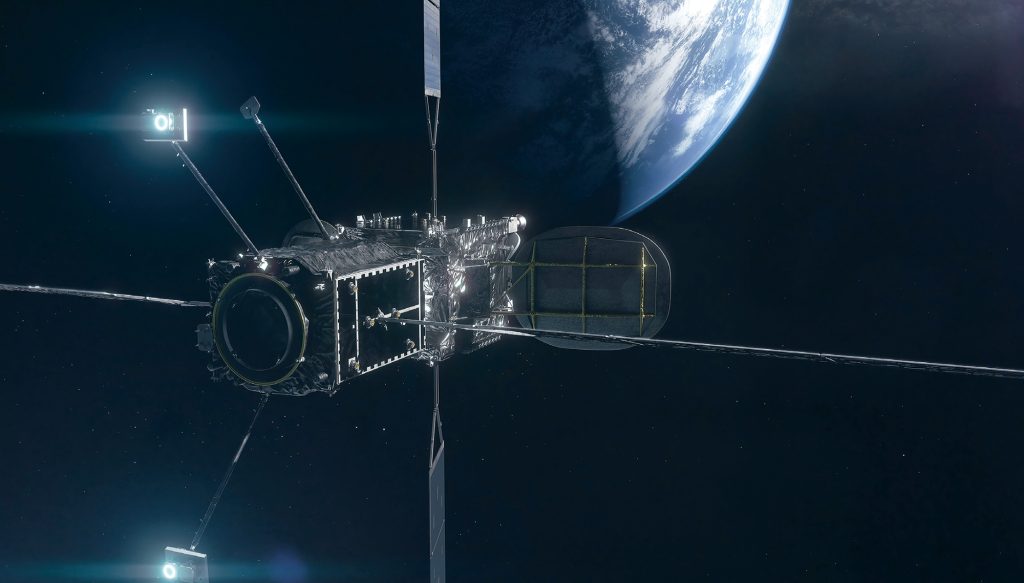

Meanwhile, in the same release announcing the PRM selection, Northrop revealed that it had received a contract from Space Systems Command to develop the Geosynchronous Auxiliary Support Tanker, or GAS-T, a spacecraft that will have enough fuel to maneuver between satellites and refuel them.

“If you had a servicer that was quite small, then you would really need to be going back to a depot frequently. And that’s part of the architecture and the trades—how much fuel is really beneficial for the vehicle that’s interacting directly with the client vehicles? And I think for us specifically, we have enough fuel that we’ll be able to refuel multiple client vehicles,” said Smith. “GAS-T is envisioned to be able to be refueled. So it could be filled up at a depot in the future certainly. But in this architecture today, GAS-T has enough fuel capacity to be able to refuel multiple vehicles. And so as part of this architecture, we don’t have to have a depot today for it to be useful.”

Smith called GAS-T a “pathfinder” program for the Space Force, and while Northrop believes the technology is mature enough to be operational, she said the contract is meant to be “iterative.”

“The information that we’re generating through S&T, getting to the requirements review, SSC will have the option to say we’d like to move forward with this to demonstrate the technology,” said Smith. “ … Ultimately we’re taking SSC’s lead for sort of how they want to move the technology forward.”