The 86th Operations Group at Ramstein Air Base in Germany is pioneering a new program that could help improve mental health outcomes for aviators across the Air Force.

The Military Aviator Peer Support (MAPS) program is a group of 32 air crew members trained to be a helpful, confidential ear for peers to discuss challenges in their personal or professional lives. The idea is to give Airmen an opportunity to talk with someone who understands their situation and who will not mark it in their records.

“The special skillset of a peer program is to allow you to speak freely to someone who understands the operational environment that you are telling your story from,” said Lt. Col. Sandra Salzman, a pilot-physician with the 37th Airlift Squadron at Ramstein who is helping spearhead MAPS.

Health care is a challenge for aviators, who often misrepresent or withhold health information from flight surgeons out of fear that they might lose their flying status. A 2023 review found that out of 264 military pilots, 190 (72 percent) reported a history of health care avoidance, 111 (42.5 percent) misrepresented or withheld information on a written health care questionnaire, 89 (33.7 percent) flew despite experiencing a new physical or psychological symptom that they felt probably should be evaluated by a physician, and 30 (11.4 percent) reported a history of undisclosed medical prescription use.

Air Force pilots said in a study last year that fear of being taken off flight duty; worries about judgment from peers and leadership; concern that providers might over-diagnose symptoms; lack of available appointments; and lack of education about health treatment for aviators were among the factors discouraging them from seeking mental and physical health care.

“Pilots attempted to ‘feel out’ responses from peers by explaining a condition as a joke or broadly talking around an issue to see what kind of response they would get,” the study said. “One pilot explained that he/she received an ‘all right, good luck’ response from a peer, which he/she perceived as negative, influencing his/her decision to not go to a clinic.”

Indeed, the prospect of going to a clinic was another intimidating factor: talking with a flight surgeon in the usual squadron buildings made the pilot “feel less trapped” than formally scheduling an appointment at a separate facility.

Military pilots are not alone: a 2022 study found that 56 percent of 3,756 civilian pilots reported a history of health care avoidance behavior due to fear of losing flying status. But the civilian pilots have an advantage: airlines and associations across North America and Europe have adopted peer support programs for pilots and flight attendants to get advice on stressful challenges before they can metastasize into a problem that risks lives or careers.

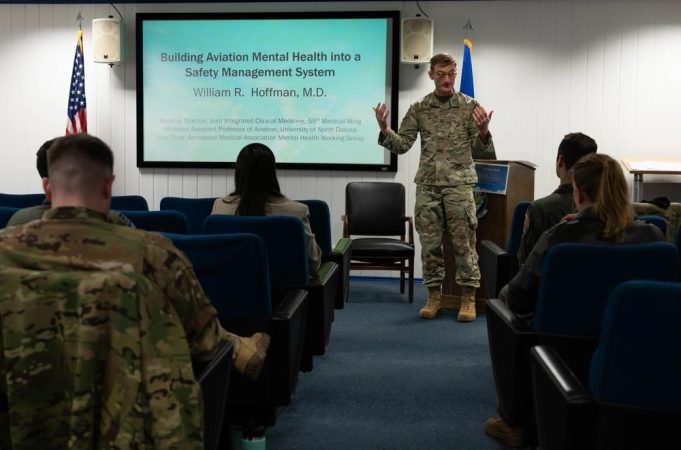

“These are people facing one of life’s usual stressors: divorce, a sick child, maybe a pilot promoted from first officer to captain, and they have a really challenging schedule flying a lot at nights, and there’s discord at home,” said Capt. William Hoffman, an Air Force neurologist and aeromedical researcher with the 59th Medical Wing at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, Texas. Hoffman also co-authored the three studies cited above and has advocated to change “lie to fly” culture for years.

“It’s a really hard job, and to connect with another pilot who understands what that’s like and can provide an empathetic, non-judgmental ear is incredibly valuable,” he added. “In the clinical literature, sometimes it matters less what strategy you use in therapy, and it’s more about a trusting relationship with your therapist.”

That may be even more true in the military, where aviators can’t always tell friends or family everything in order to preserve operational security.

“It’s really hard to explain to your spouse or your friend, ‘you know, I was flying into a dangerous place, and we were watching for these dangerous things. And also, this person keeps pumping this button,’” Salzman said. “So to have somebody that already understands the environment, you can just be like, ‘they kept keying their mic every time I tried to talk.’ Just to say it out loud and get it off your chest and have someone say, ‘I’d be upset too,’ can help you feel better.”

Then-Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force JoAnne Bass said in 2024 that only two out of every 10 Airmen who seek mental health need clinical support, according to mental health providers. “The other eight just need to know someone cares,” she said.

There are no formal scientific studies of whether these peer support programs work, Hoffman said, but informal experience suggests that perhaps as many as 95 percent of pilots who seek peer support help don’t require escalation to a mental health provider.

“All those people would probably otherwise just forgo care altogether, or get worse until they actually need to see a mental health provider,” Hoffman said.

Bringing It to the Air Force

Salzman was inspired to bring aviator peer support to the Air Force after seeing Hoffman and civilian aviation peer support leaders present about the topic at an Aerospace Medical Association conference last June.

“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, we’ve got to have one of these,’” she recalled.

Salzman worked with Hoffman, the 59th Medical Wing, and Stiftung Mayday, an aviator peer support program based in Germany. Stiftung Mayday began in the 1990s, building its program off skills taught by the U.S. Air Force sexual harassment/assault response and prevention team stationed at Ramstein Air Base. Stiftung Mayday serves civil aviators across the European Union, the lieutenant colonel said. It came full circle when Stiftung helped Salzman design a training program for Air Force peer support wingmen.

The training takes about two days and involves both computer-based training and in-person role play.

“A moderator helps you reframe issues to see actionable options with positive side effects and get comfortable with asking difficult questions and then shutting up to hear the answer,” Salzman said. “That is the hardest part of all: being quiet and listening.”

The program started in November and there are now 32 peer support wingmen: about 10 peer support wingmen per squadron at the 86th Operations Group, including pilots, loadmasters, flight attendants, and air traffic controllers. A list is published in the group’s electronic flight bags, along with contact information and where to find them.

Group members “can reach out to them via any of the ways that they have listed on there, and ask them, ‘Hey, can I chat with you for a few minutes?’” Salzman said.

MAPS is the latest in an ecosystem of support programs, including crisis action teams, finance teams, and substance abuse counselors, Salzman explained. But since MAPS is made up of fellow aviators who work alongside their peers, they serve as a first line of defense for addressing life’s problems, and as a way to point to other resources if needed.

“It is so easy to de-escalate a brewing issue if you can just get it off your chest,” Salzman said.

Ground rules are important: MAPS does not keep records of its conversations to preserve confidentiality. Peer support wingman also must report any “red flag” events, such as having suicidal or homicidal intent or breaching operational security. MAPS wingmen can also talk with Salzman or Lt. Col. Darrell Zaugg, a psychiatric flight surgeon co-leading the effort.

“They don’t have to name names, that way I’m not putting stress on them,” Salzman said. “I don’t want them to go to sleep with a secret that makes them uncomfortable.”

Stiftung Mayday had just 24 meetings in the first year of its program. By comparison, about 50 people consulted with MAPS in its first six months, and about 40 percent of them discussed flying-related issues, Salzman estimated. Only a few of the 50 needed professional help.

“Commanders have come to me and said, ‘I can tell that what you’re doing is having an impact for the better within the morale of the squadron,’” the lieutenant colonel said.

“Typically our community is very stoic: everything is fine and you herk the mission and you don’t complain,” she explained. “So to pull people from their shells and say, ‘it’s all right, if you’re having a thing, I know you can still fly. What can I do to help?’ That means a lot, and it changes the culture a little bit.”

Next Steps

Hoffman said cultural change and buy-in from leadership is ultimately needed to replace “lie to fly” with something more proactive in terms of treating mental and physical health.

“Commanders at the front telling stories of what success looks like is going to be where I think real progress is going to be made,” Hoffman said, pointing as an example to former Air Mobility Command boss Gen. Mike Minihan’s efforts to reduce the stigma around mental health treatment.

“When there’s a leader like that who is clearly mission-focused, but acknowledges that people are also living their life, and it’s normal to have feelings and challenges, I think that really brought the narrative forward in a major way.” Hoffman said.

For now, Salzman plans to study for a year how many people use the program and what support agencies are most needed. Depending on the data, she’ll make a recommendation to Air Force Medical Command whether the program should expand beyond Ramstein. Salzman has an exportable package for starting up similar programs in other units. The only cost would be possibly paying for a license to a United Kingdom-based software company for the computer-based training, should MAPS be scaled up across the service.

“Beyond that, it is the lowest cost program that I’ve ever seen that can make a cultural shift in a flying unit, which is really hard to do,” she said.

Hoffman said the next step is a larger-scale feasibility study for expanding peer support in the Air Force, but it would require funding. That funding may have to come from the operational community, since peer support does not look like typical medical treatment and there is little foundational research to serve as the basis for a formal medical study, he said.

“It’s not really a medical problem, it’s an operational problem,” Hoffman explained. “So we really need the operational community to sponsor work on this.”

By improving aviator well-being, Salzman said, MAPS should also make flying safer.

“Mutual support is something aviators understand in the air,” she said. “When we’re provided with the tools to apply that on the ground as well, it only makes our units stronger and it decreases our operational risk factors by an unmeasured amount.”