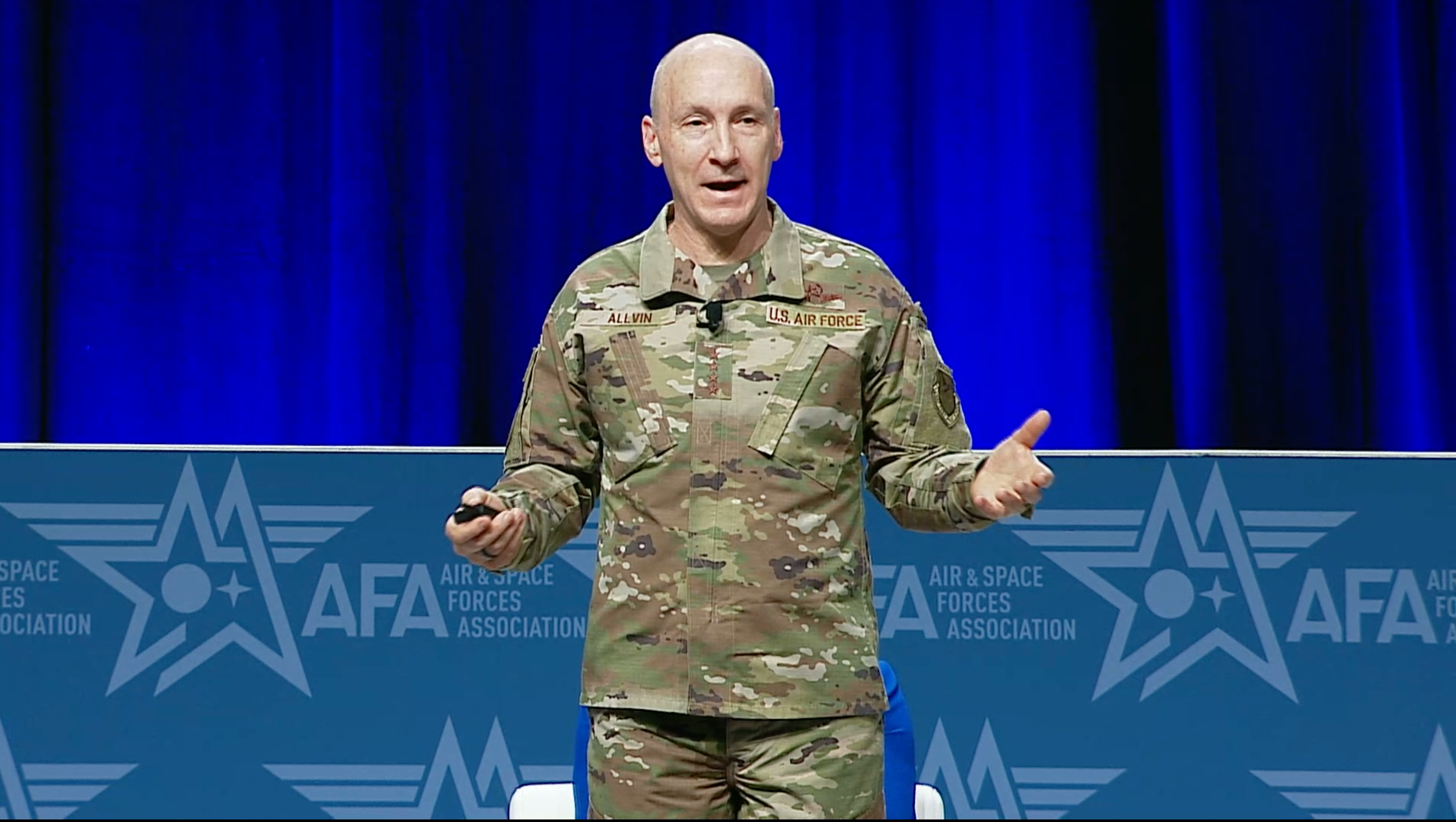

AURORA, Colo.—While the Air Force is undergoing sweeping changes as part of its re-optimization for Great Power Competition, the Space Force’s to-do list is shorter—but still with some major changes driven by the need to adjust to a changing domain, Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman said at the AFA Warfare Symposium.

“That shift to an operational phase where we have to now build and then maintain space superiority in order to continue to provide the services that the force has come to count on is what the real transformation is,” Saltzman said during the conference’s opening session Feb. 12.

Saltzman compared the transformation to that of converting a Merchant Marine to a Navy—preparing the Space Force to operate in a contested domain.

Space Futures Command

Perhaps the biggest change is the planned establishment of Space Futures Command, meant to answer long-term questions such as “Are we developing capabilities for the long term to continue to have advantages and maintain those advantages for years to come in the future? Are we evaluating the future operating environment? Are we evaluating the missions that we’re going to be asked to take on? Do we know how we’re going to accomplish that?” Saltzman said.

This new field command—similar to Army Futures Command—will include three centers aimed at answering those questions.

The Concepts and Technology Center will focus on evaluating the future operating environment, assessing adversary technologies, and devising operational concepts. A new Wargaming Center “helps us evaluate technologies … helps us experiment with new technologies,” Saltzman said.

Finally, the Space Warfighting Analysis Center, currently a direct reporting unit, will leverage advanced analytics and modeling to inform decision-making and shape the future force design, Saltzman said.

Through the new command, the Space Force aims to stay ahead of emerging threats and maintain its competitive edge in the space domain. The Space Futures Command will be the service’s fourth field command, following on Space Operations Command (SpOC), Space Systems Command (SSC), and Space Training and Readiness Command (STARCOM).

Preparing Guardians

Big changes are also coming for how the Space Force will prepare its personnel. Reflecting on current processes, Saltzman suggested they are not fully adequate to meet the evolving demands of space warfare, characterized by high operational tempo and technological complexity.

For that, the Space Force will redesign its Officer Training Course so that all Space Force operators will have a better understanding of every other career field. On top of that, the service will implement new career paths.

“But that’s not going to stop there,” Saltzman added. “We have to recognize that all of our operators and all of the Guardians are going to need similar kinds of training and experience different from what they’ve had in the past.”

With that, the service plans to expand educational and developmental opportunities for all Guardians in the future, including the enlisted personnel and its civilian work force.

Bolstering Readiness

Saltzman also laid out a plan for ensuring the Space Force’s preparedness for the challenges of great power competition. Drawing from his experience as a squadron commander, Saltzman detailed the elements of readiness: “It’s the people, it’s the training, it’s the equipment, and it’s the sustainment.”

How the Space Force assesses that readiness needs a fundamental overhaul, Saltzman said, noting that “we have to rewrite the standards for readiness centered around a contested domain.”

Saltzman also stressed the need for advanced training and tactics to counter adversaries effectively.

“We have to redesign our architectures, redesign the systems to do our missions so they’re resilient against an adversary,” Saltzman said, highlighting the need for swiftly enhancing the service’s capabilities but pointing out the importance of the sustainability of those capabilities in the long term. For that, the service plans to create a series of exercises with an increase in scope, tempo, and complexity to fit within a broader Department-level framework. The assessment results from these trainings will shape force design and development.

Power Projection

As a service, the Space Force primarily deploys in place, making its force generation model unique. To that end, Saltzman said the service would establish “combat squadrons” meant to fit in with the department’s “units of action” concept for presentation to combatant commanders.

While combat squadrons will focus on day-to-day functions required by combatant commanders, mission squadrons will retain some ability to focus on high-end, advanced readiness activities. He added that these tasks will be rotated through the Space Force generation models, so that “the people on the ops floor are both ready if we have to fight tonight against the adversary, but also can respond to those day-to-day tasks.”

“What we’re really doing is building combat-ready forces,” Saltzman added. “If we can’t build combat-credible units, we have no chance of deterring a very capable and determined adversary.”