As the Air Force considers privatized housing for unaccompanied Airmen at isolated bases or in high-rent areas, the service is looking to the Navy for lessons on how to avoid the problems that have marred privatized military family housing for years.

Specifically, Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force David Flosi told lawmakers March 20 that the service is tuned to the Navy’s Public Private Venture program, which Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy James Honea said has successfully housed unaccompanied sailors for more than 20 years.

“We’re paying close attention to the Navy and the lessons that they’ve learned so that we don’t replicate some of the mistakes that came through our initial contracts that we wrote with privatizing military family housing,” Flosi said at a hearing before the House Appropriations subcommittee on military construction and veterans affairs. “We’re also learning to be more accountable through that process as well.”

The Air Force is planning to invest $1.1 billion in restoring and modernizing its dormitories, the largest such investment in more than a decade, Flosi said. The plan touches about 60 installations— 23 of which are to be completed in fiscal 2024, installations boss Ravi Chaudhary told lawmakers in February.

The fiscal 2025 budget includes funding to revamp housing at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., Barksdale Air Force Base, La., Cannon Air Force Base, N.M., Goodfellow Air Force Base, Tex., and Ellsworth Air Force Base, S.D., Flosi said.

The Air Force’s first privatization project for unaccompanied housing will take place at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., though the chief did not say when that project will begin. Most military barracks, which are called dormitories in the Air Force, are run by the government, but the Navy and Army are also looking to explore or expand privatized barracks.

Chaudhary told Air & Space Forces Magazine he was confident about overseeing privatized dormitories.

“If we didn’t capture all of the lessons learned from privatized housing, we wouldn’t be worth our salt,” he said earlier this month. “So yes, any privatized approach will capture the lessons, and if, anything, make it more robust so that we don’t get into the situation that we had in 2019 with privatized housing.”

Problems with privatized family housing actually became widely known in 2018, when Reuters published an investigative series of articles on how inconsistent oversight and insufficient standards led to unsafe family housing and unaccountable contractors across the armed forces. Subcommittee ranking member Rep. Deborah Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.) was skeptical contractors could improve their performance in unaccompanied housing.

“I would envision us having, in the not too distant future, hearings like we had with family housing companies,” she said at the March 20 hearing, “because the privatization process is a failure in terms of maintaining the quality of life of housing.”

The senior enlisted leaders of each branch said they shared Schultz’s concerns but said they were being careful not to repeat past mistakes.

“We also share some concerns from past history, which is why we are measuring twice to cut once in this phase,” said Sergeant Major of the Army Michael Weimer, whose service is exploring privatized unaccompanied housing at Fort Meade, Md., U.S. Army Garrison Miami, Fla., and Fort Irwin, Calif.

Honea, the top enlisted sailor, said the privatized military family housing debacle represented a failure of oversight on the part of military leaders. The Navy’s Public Private Venture (PPV) program was an exception, he said, especially for barracks like Pacific Beacon in San Diego, which bills itself as “resort-style” housing for single enlisted sailors, complete with a rooftop pool and “unmatched views of the city.”

“Private barracks like Pacific Beacon have been operating for 20-plus years largely as a success because we’ve not abdicated our responsibility in providing that oversight to ensure that our private partner is delivering on the promises that they’re going to make,” Honea said. “If we continue along that way, we’re going to do resoundingly well.”

The advantage of privatized housing is that it allows services to meet changing needs faster than with military construction funds, which can take years to turn into bricks and mortar.

Flosi said privatized housing could be particularly useful where Airmen suffer excessive commute times due to a lack of housing in remote areas. For example, Rep. Susie Lee (D-Nev.) said Airmen at Creech Air Force Base, Nev., spend as much as $400 per month on gas in order to drive 100 miles to work and back every day. Privatized housing could also be useful in areas where local rent prices outpace the basic allowance for housing, Flosi said.

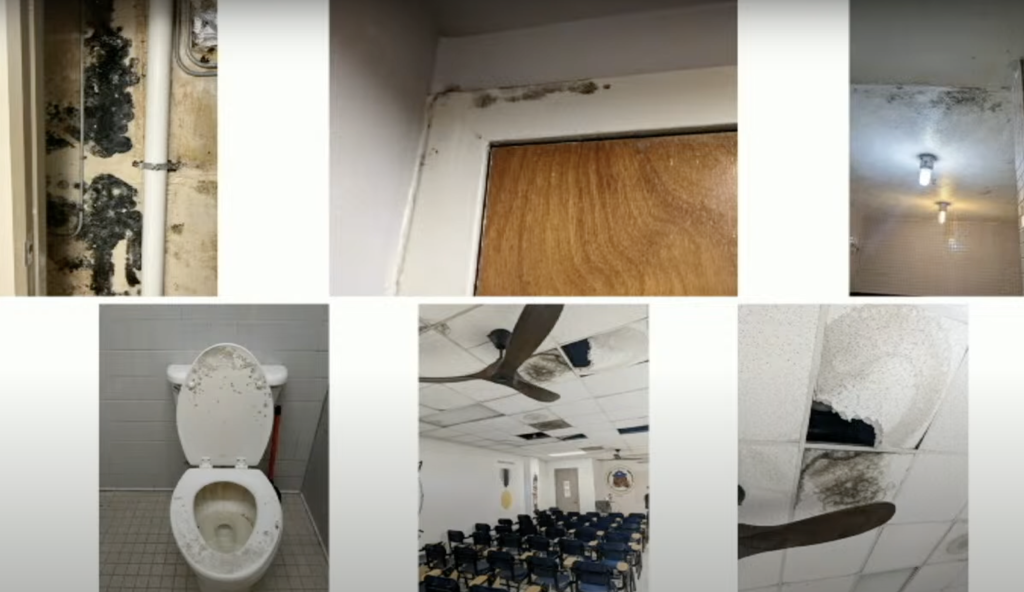

The government’s own housing has had issues of its own. The Government Accountability Office published a report last year identifying serious flaws in how each service assesses its unaccompanied housing, including the Air Force. The report flagged missing heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems, broken fire safety systems, mold or mildew growth, water quality problems, pests, insufficient oversight from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and other issues.

The index for evaluating housing conditions may also be in need of an update: the GAO analysis showed that nearly 50 percent of Air Force dormitories considered at risk of significant degradation had a condition score of 80 or above. There also is no Air Force-wide system for monitoring tenant satisfaction, which hampers leaders’ ability to perceive and respond to flaws. Privatized military family housing suffered from similar issues across the services, GAO noted.

“These problems are, unfortunately, not dissimilar from the ones we have observed and documented in privatized family housing,” Elizabeth Field, GAO’s director for defense capabilities and management, said in September. “The only real difference is that the Defense Department has felt more pressure in recent years to fix the problems in family housing than it has to fix the problems with barracks.”

For his part, Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force John Bentivegna said the Space Force was not looking into privatized unaccompanied housing, but since many new Guardians are older and may have families or postgraduate degrees, the Space Force is “looking at what that means for dorm life, if you will, and what the infrastructure looks like.”

Still skeptical, Wasserman Schultz asked Honea what about about the Navy’s PPV agreements gave him greater confidence in terms of overseeing private contractors. He said did not have an answer ready and promised to follow up with her.

“I just hope this raises caution flags on moving forward on barracks and unaccompanied housing, because I don’t trust them [private housing contractors],” Wasserman Schultz said. “They are willing to take massive fines just as the cost of doing business, and then they do it again. So I would just really consider this a very big caution flag here that could down the road result in language coming from me.”