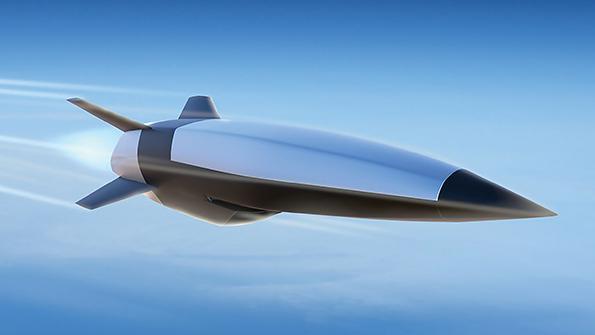

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has assigned the designation XRQ-73 to its newest “X-plane,” an autonomous flying wing reconnaissance aircraft prototype with extra-quiet propulsion that is expected to fly this year, the agency announced June 24.

The new aircraft also goes by the program acronym SHEPARD, for “Series Hybrid Electric Propulsion AiR Demonstration,” and is being developed by Northrop Grumman and its Scaled Composites subsidiary. It is powered by a hybrid electric system which converts fuel to electric power and is part of DARPA’s X-prime program.

The program is builds upon hybrid technologies and other components developed as part of the “Great Horned Owl” predecessor project run by the Air Force Research Lab and the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency, DARPA said. The Office of Naval Research and AFRL are also partners on SHEPARD.

Other involved companies include Cornerstone Research Group, Inc.; Brayton Energy, LLC; PC Krause and Associates, and EaglePicher Technologies, LLC, DARPA said.

DARPA revealed that the XRQ-73 is described as a “Group 3” uncrewed aerial system, coming in at 1,250 pounds, just under the high end of that category’s weight range, between 55 and 1,320 pounds. Group 3 UAS also fly below 18,000 feet, and between 100 and 250 knots airspeed. The then-unnamed aircraft was expected to fly in calendar 2023, but DARPA did not offer an explanation as to why it did not.

The Great Horned Owl project began in 2011 and bore the designation XRQ-72. It used upper-surface propulsors, and so was not stealthy, but the XRQ-73 is a flying wing with engines buried in the planform, clearly intended to have radar low observability in addition to noise reduction. The GHO was to be powered by either gasoline or diesel, but it’s not clear if that requirement also applies to the SHEPARD. Most details of the program remain classified, but the hybrid electric approach is intended to significantly extend the travel and on-station time of a drone in this class.

DARPA said the XRQ-73 could be “rapidly fieldable.” The SHEPARD effort has been underway for about four years.

The SHEPARD vehicle will have an “operationally representative fuel fraction and mission systems, while staying below the Group 3 UAS weight limit,” DARPA said on its website.

An IARPA program briefing slide from 2011 noted that noise is the “number-one signature” issue for low-flying UAS. A hybrid power approach was chosen to eliminate gearbox noise on the GHO.

Scaled Composites is doing the fabrication; Northrop and its Scaled subsidiary are also working on the Defense Innovation Unit/Air Force Blended Wing Body demonstrator, seen as a potential prototype for a stealthy transport.

SHEPARD program manager Steve Komadina said in a DARPA press release that the idea behind DARPA’s X-prime program “is to take emerging technologies and burn down system-level integration risks to quickly mature a new missionized long endurance aircraft design that can be fielded quickly.”

The XQR-73 program “is maturing a specific propulsion architecture and power class as an exemplar of potential benefits for the Department of Defense,” Komadina said.

DARPA did not say whether the XQR-73 will be officially connected to ongoing Air Force Collaborative Combat Aircraft projects, but a Pentagon official said such efforts are coordinated to find “aligned technologies.”

SHEPARD “is an existing option” to AFRL’s Great Horned Owl contract, Komadina said in an undated description on DARPA’s website. The SHEPARD will leverage what was learned on GHO’s hybrid electric architecture “and some of its component technologies, and quickly mature a new mission-focused aircraft design that can be fielded with the objective of first flight in 20 months.”