An electrical power disruption wreaked havoc on an F-16’s flight and navigation instruments, and poor weather meant the pilot had no other way of gaining his bearings, resulting in a fiery crash in South Korea last year that destroyed the $29 million aircraft, according to a new U.S. Air Force report.

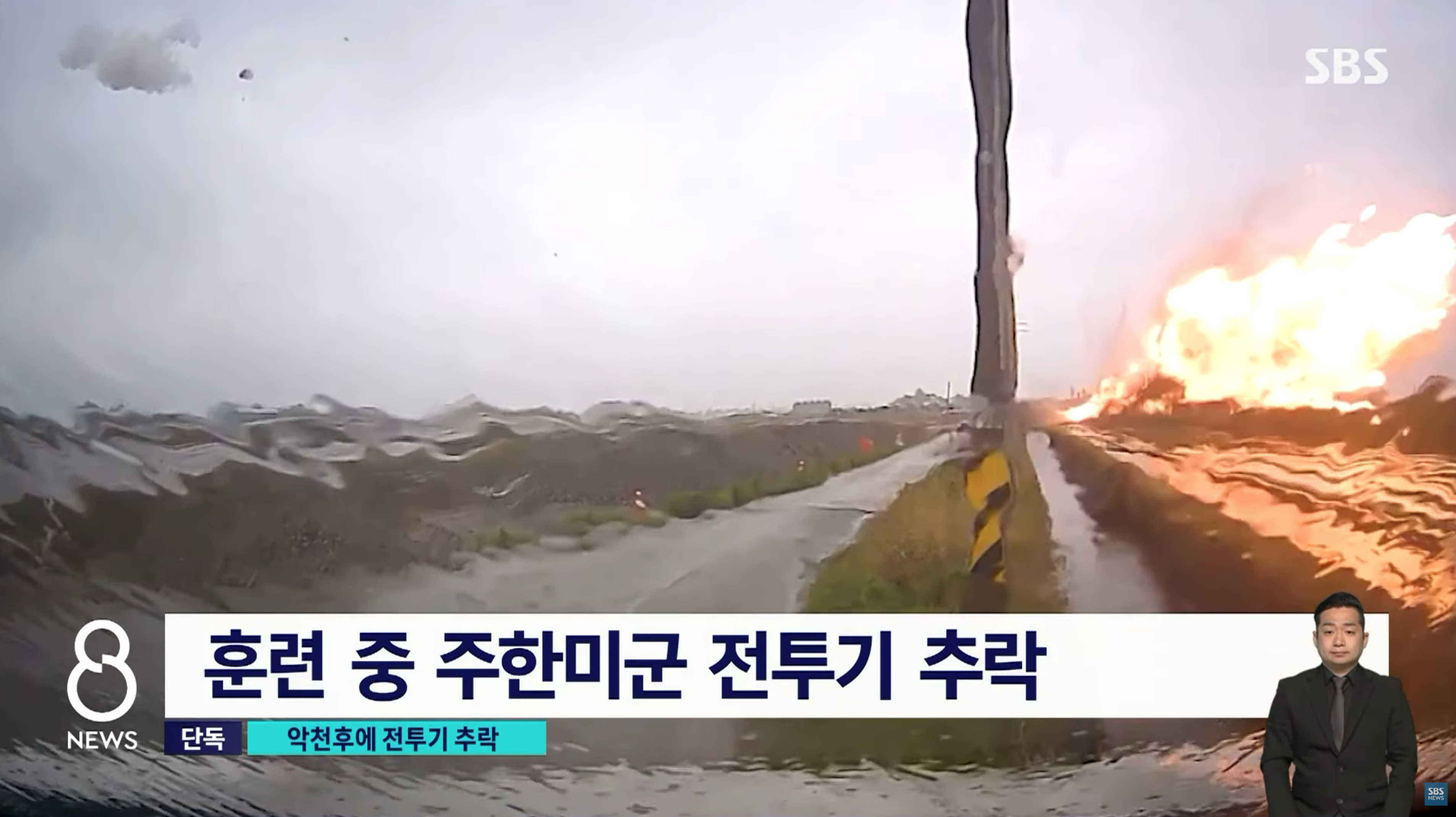

South Korean broadcasters released dramatic CCTV footage of the May 2023 mishap, which showed the pilot ejecting safely before the crash, but the cause of the incident was unclear at the time.

The pilot and F-16 were from the 8th Fighter Wing at Kunsan Air Base, but they took off from Osan Air Base at around 9:30 a.m. local time on May 6, 2023, as part of a four-ship formation participating in a local exercise. The weather was rainy and too cloudy for the pilot to see his flight lead ahead of him and he had to use his radar to lock on.

Using data from the aircraft’s “black box,” investigators determined that just 11 seconds after takeoff, the F-16 experienced a partial electrical power issue. The exact cause of the problem will never be known, investigators said.

“Given the lack of available evidence, and the many potential causes of the partial electrical failure, to include any piece of electrical equipment or any stretch of wiring, it is not possible to determine the actual cause of the electrical power loss,” they wrote.

Regardless, in rapid succession—less than 30 seconds—essential systems started to fail, including:

- the Inertial Navigation System, “which displays flight data such as aircraft heading and relation to the horizon,” the report states

- the Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System (Auto-GCAS), which allows the aircraft to take over from the pilot if it senses it is about to crash

- the Data Entry Display, which shows data inputted by the pilot

- the horizon or attitude indication lines, or “pitch ladders” on the Heads Up Display

- Communication with anyone outside the aircraft

All this prevented the pilot “from being able to accurately tell where the horizon (i.e. wings level attitude) is with his primary horizon display … from changing his navigation equipment settings and … from initiating an automatic aircraft recovery.”

While the systems did not display warning messages, the pilot recognized that the data from his primary horizon display, particularly airspeed and attitude, were inaccurate. A brief break in the clouds allowed him to fly using visual cues, but upon re-entering the bad weather, he tried to use the backup horizon display, only to find that that system was also displaying inaccurate data.

“Multiple attempts to try and determine where the horizon was by cross-checking between the primary and standby [Attitude Directional Indicator] were unsuccessful,” the report states. The investigators indicated the pilot was largely helpless at that point, and compared the situation to “when you push on the gas in a car and expect the speed to go up, but the speed goes down.”

By the time the aircraft dipped below the cloud cover, the pilot determined he was flying too low and at too steep of an angle to recover and ejected at 710 feet above ground level, less than three minutes after takeoff. The aircraft crashed close to where he landed, in an agricultural field. Debris flew some 300 yards, and “there was a significant localized post-impact fire at the impact crater,” the report states, but there were no casualties.

The accident investigation board cited two main causes for the crash, with no contributing factors: the power disruption’s effects on the F-16’s instruments and the poor weather conditions preventing the pilot from being able to fly visually.

“The mismatch in data provided by the primary and standby attitude indicators, due to the power disruption, caused the [pilot] to become spatially disoriented and unable to maintain aircraft control in the weather and at a low altitude,” the report concluded. “The absence of either factor may have prevented this mishap.”

The aircraft was completely destroyed, with the damages estimated at $29.39 million. The incident was the first of three USAF F-16 mishaps in South Korea in nine months, leading to a brief pause in flight operations. Officials have said they do not believe the incidents are related. This is the first incident for which an accident investigation board report has been publicly released.