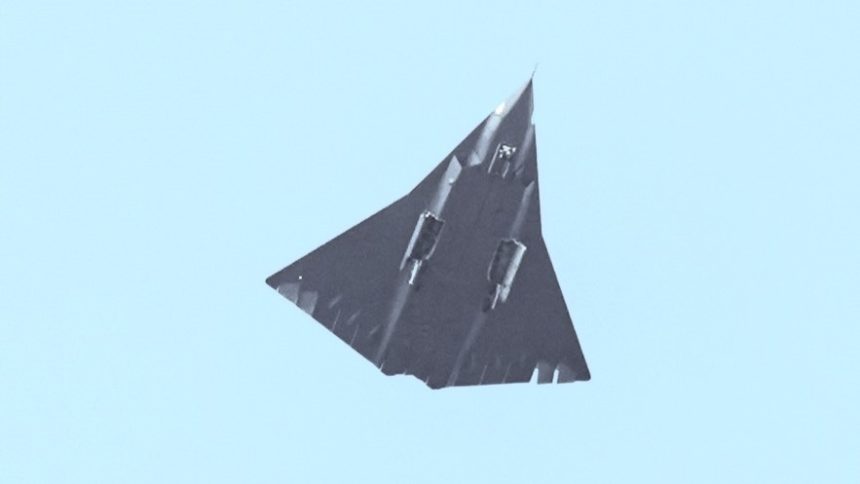

Imagery of two new, tailless Chinese military aircraft disseminated on social media last week likely reveals a prototype stealth medium bomber and a new lambda-winged technology demonstrator, aerospace experts and former Air Force officials told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

The larger aircraft could be analogous to the FB-22 medium stealth bomber considered but not adopted by the U.S. Air Force in the early 2000s.

The larger aircraft, speculatively dubbed JH-36 by the aviation press for the “bort” number seen in some images, is likely the “medium bomber” referenced in the most recent edition of the Pentagon’s annual report on China’s military power, released in mid-December. Since 2019, the annual report has mentioned a “JH-XX” medium bomber under development.

“The [People’s Liberation Army Air Force] is developing new medium- and long-range bombers to strike regional and global targets,” the most recent report stated, adding only that these aircraft are likely to have extremely low observable characteristics.

The PLAAF is known to be developing a flying-wing large bomber, called the H-20, similar to the American B-2, but the aircraft seen in December differs substantially from what that aircraft is expected to be.

“The Air Force has been closely monitoring China’s ongoing military modernization efforts,” a service official said on background. “This development is consistent with our understanding of China’s strategic objectives and long-term force planning. Their new weapons systems introduce additional complexity in the PLA, which requires highly skilled personnel to actually employ them to the max extent of their capability.”

The “JH-36” seen in the video and still imagery—which was not censored or commented on by the Chinese government—is a large aircraft, about 30 percent larger than the 70-foot J-20S two-seat “Mighty Dragon” apparently flying chase in the images. The new flying wing delta airplane has no vertical control surfaces but has five flaperons on each side of the trailing edge of the wing, heavily deflected to near-vertical in some of the images, and moving independently. A tailless aircraft is inherently stealthier than one with vertical control surfaces, offering less of a target for radar, and would typically be lighter, allowing for extended range.

The quirky, many-element flaperon system may also mean “they haven’t mastered thrust vectoring and control,” an industry expert said, adding “they’re not 10 feet tall.”

The aircraft is likely a Chengdu product, as it was chased by Chengdu’s J-20S.

The aircraft has three inlets: one dorsal inlet at mid-fuselage, and two ventral inlets near the nose, in a parallelogram-shape reminiscent of the F-22, and three apparent above-wing exhausts, suggesting three engines. The exhausts are similar to those on the B-2 and Northrop Grumman’s YF-23 competitor in the Advanced Tactical Fighter program, which was won by Lockheed with the F-22. The dorsal inlet is different from the other two, but seems shaped for stealth, as it is reminiscent of that in Northrop Grumman’s unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Have Blue stealth demonstrator program won by Lockheed.

Three engines would make the aircraft very heavy—or at least reduce its range and payload—and experts speculated that the reason for three may have to do with generating power for intense electronic warfare applications or to mix bypass air with the exhaust air to cool it and reduce the aircraft’s heat signature.

According to the Pentagon report, China’s indigenous engine industry is unlikely to have matched the technology in the American Adaptive Engine Technology Program (AETP), which produced prototype engines using bypass technology that could be optimized for specific thrust or loitering, with additional stealthiness as a byproduct. An expected competition between those engines—one built by GE Aerospace and one by Pratt & Whitney—was meant to upgrade the F-35 but was abandoned because they could not fit all variants of that fighter.

One aerospace technologist said the third engine is “either a brilliant solution to have both power and stealthiness” or “dumb, flying around with the dead weight of unused propulsion mass.”

He speculated that the ventral engine inlets may be used for takeoff and landing, while the ventrally-fed engine might be used for cruise, thus extending range.

Topside views of the JH-36 aircraft were more limited, grainy and indistinct, and it could not be ascertained if the cockpit is for one or two crew, in tandem or side-by-side. The opaqueness of the canopy in the available images could even suggest it is an uncrewed airplane and that the canopy is merely painted on. The use of a two-seat J-20S as chase plane could lend support to this speculation, as the backseater might have been controlling the JH-36 or standing by to take control in an emergency.

The jet has an internal weapons bay, and tandem wheels, typically used on heavy aircraft. The bays were not opened while cameras were rolling. The aircraft also seems to have large apertures adjacent to the nose, reminiscent of the Distributed Aperture System (DAS) on the F-35, but significantly larger.

One industry expert said the JH-36 reminds him of the Lockheed FB-22 because of its size, and because some of its forward-fuselage features reflect the heritage of the J-20. He noted that the FB-22—an adaptation of the stealth fighter to hold more weapons and fuel—was offered when the Air Force’s Next-Generation Bomber was canceled, creating a potential gap in penetrating bomber capacity. The Chinese medium bomber may have had a similar genesis, if their developers have run into problems delaying the H-20’s introduction.

“The FB-22 would have been a pretty straightforward stopgap,” he said, “re-using the fuselage and systems of the F-22 with an extension and bigger wings to hold more weapons and fuel.” The Air Force considered the concept but dropped it when it was approved to undertake a new long-range bomber program.

“Given the likely first steps in a Taiwan scenario, a medium-range bomber makes sense for the PLAAF,” an industry technologist said. However, the aircraft could also be “a technology demonstrator, or even a fighter. We just can’t tell at this point,” an industry expert said.

The other aircraft revealed, in images with diminished detail, is also a tailless aircraft with a lambda-style wing planform and an overall arrowhead-like design.

It has a two-engine exhaust system similar to that of the F-22, potentially suggesting that China is exploring a number of ways to reduce the heat signature and possible thrust vectoring of combat aircraft engines. Apparently smaller than the JH-36, the second, fighter-size aircraft had tricycle landing gear. It was chased by a J-16, an Su-27 variant made by the Shenyang Aircraft Corp., so it may be a Shenyang product. It seems unlikely the two new aircraft are competitors, given the apparent difference in their size.

Imagery of the second aircraft did not offer a clear view of the upper nose area, so it’s unclear if there is a cockpit or if it is potentially an uncrewed vehicle in the same class as the first increment of the Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft program.

The date of the imagery’s release, Dec. 26, is significant in that it is the birthday of Mao Zedong, the PRC’s founder and longtime leader, and the date on which the J-20 was similarly unveiled on the internet in 2010. Uncoincidentally, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates was on a visit to China at the time, and Gates had previously predicted that China would not have a fifth-generation stealth fighter for another decade. In his memoir, Gates called that unveiling “about as big a ‘f— you’ as you can get.”