Adversaries may not yet fear a U.S. response to cyberattacks, but they no longer think America is standing idly by.

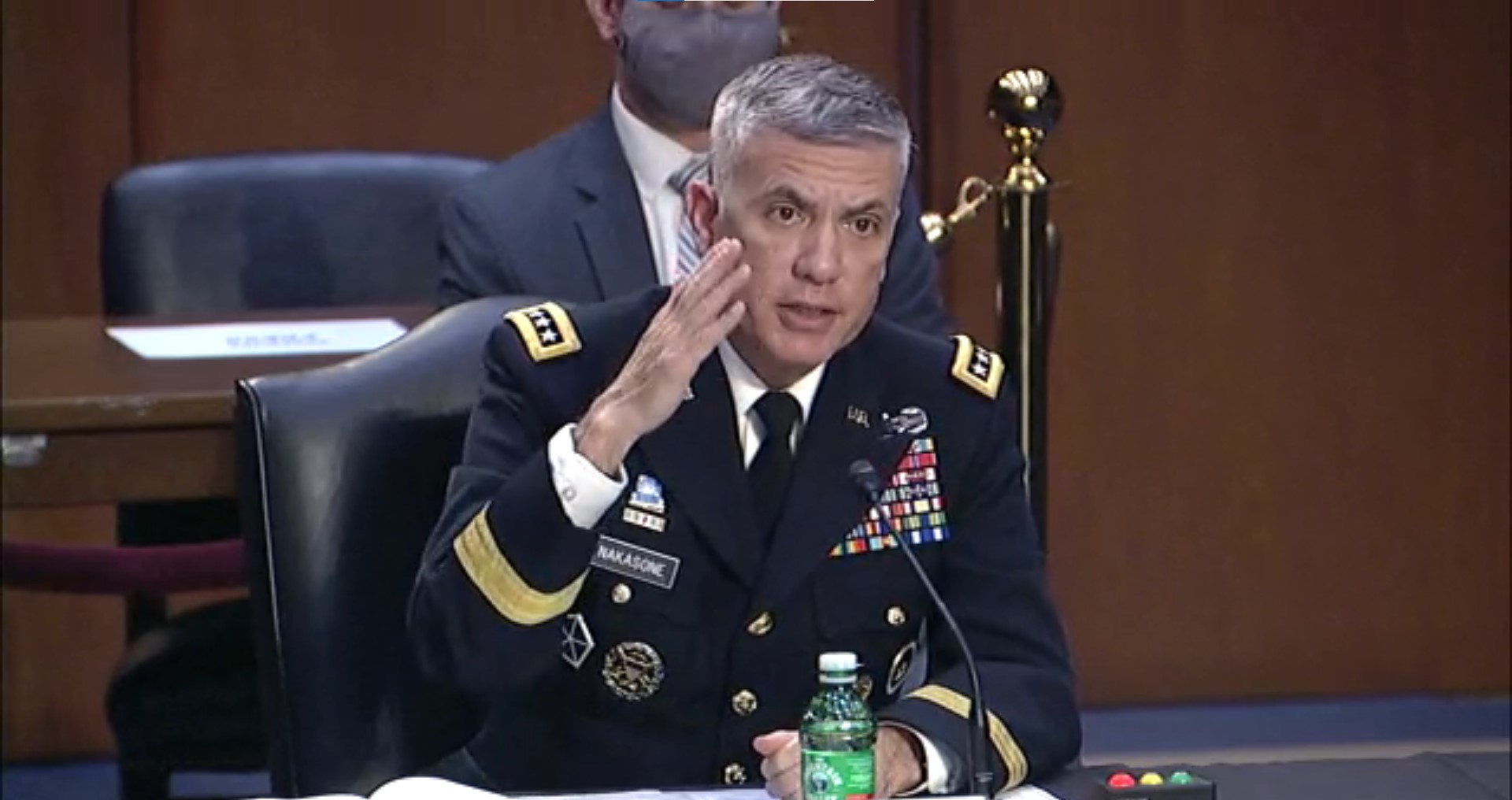

Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) pressed Army Gen. Paul M. Nakasone, commander of U.S. Cyber Command, on the issue during a Senate Select Committee on Intelligence hearing April 14. “Do our adversaries fear our response in cyberspace?” King asked. “Are they deterred to the point of changing their calculus as to whether or not to launch a cyber intrusion or an attack against us? Is there an adequate deterrent or is this something we still need to establish as a matter of policy?”

Nakasone said he was “not sure” adversaries feel deterred. “But here’s what I know that our adversaries understand that’s different today than it was several years ago,” he said: “We are not going to be standing by on the sidelines, not being involved in terms of what’s going on with cyberspace and cybersecurity.”

Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines testified along with Nakasone and the directors of the CIA, FBI, and Defense Intelligence Agency. All agreed that China poses the biggest threat, from its practice of “vaccine diplomacy” to building influence with countries in need, Haines said, to its ability to hack infrastructure and steal intellectual property from industry, universities, and government labs.

At a hearing following the release of the 2021 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, the intel chiefs elaborated on threats ranging from cyberattacks on water systems, power grids, and other critical infrastructure to cybersecurity “blind spots,” such as hacking operations run from inside the U.S., which are harder for the CIA and other internationally focused agencies to monitor.

FBI Director Christopher Wray said no other nation “presents a more severe threat to our innovation, our economic security and our democratic ideas” than China. “The tools in their toolbox to influence our businesses, our academic institutions, our governments at all levels, are deep and wide and persistent,” he said.

After China, the intel chiefs idenfied the next greatest threats, in order:

- Russia. Russia will continue to use its “technical prowess” try to erode U.S. influence and western alliances, Haines said. She said Russia employs mercenary operations, assassinations, arms sales, and malign influence campaigns, such as interfering in U.S. elections. Such techniques are increasingly bold and make little effort to mask the activities.

- Iran. Iran aims to “project power” in its region, Haines said, and to “deflect international pressure” by using Iraq as a battleground for influence. “Iran will also continue to pursue a permanent military presence in Syria, destabilize Yemen and threaten Israel,” Haines said.

- North Korea. The Kim Jong Un regime will try to “drive wedges” between the United States and its allies and could resume testing nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles, the chiefs surmise.

Sen. James Risch (R-Idaho) said global cyber trends are “worrisome,” with state actors involved in cyber activity that threatens us. Then, pressing on the issue of response and deterrence, he spoke for a number of his panel members: “I think, probably, the reason is there doesn’t seem to be that much of a price they pay for this.”