The U.S. mission in Afghanistan will conclude Aug. 31 with almost all American personnel and equipment withdrawn from the country, said President Joe Biden on July 8. He also promised that Afghan interpreters will have a place in the United States after the U.S. leaves the country.

Biden said military commanders have requested a quick withdrawal, noting that “in this context, speed is safety.” On the ground, U.S. forces quickly retrograded, sometimes leaving major bases in the middle of the night.

“Thanks to the way in which we have managed our drawdown no one—no U.S. forces or any forces—had been lost,” Biden said. “Conducting our drawdown differently would have certainly come with increased risk of safety to our personnel. To me, those risks are unacceptable.”

Until the end of August, U.S. forces will maintain the same authorities they have had for “a while” to protect themselves and conduct airstrikes. Following that, U.S. officials are working with partner nations on ways to protect the international airport in Kabul and maintain a presence at the U.S. embassy in that city to protect the diplomatic presence.

The White House and the State Department are coordinating efforts to bring Afghan interpreters and translators out of the country on special immigrant visas, with flights beginning this month. Biden also called on Congress to change the special immigrant visa law to speed up the process and allow the interpreters to stay in the United States while they await their visas.

Biden said he wants to send the message that “there is a home for you in the United States if you so choose. We will stand with you, just as you stood with us.”

Pentagon spokesman John F. Kirby said in a July 8 briefing that the military’s role is identifying installations outside the continental United States that could house potential immigrants. This includes U.S. bases on the American territory of Guam and bases in which there is an American presence abroad. There is also potential to send the visa applicants to other nations unrelated to the U.S. military presence.

“There’s not one part of the world we’re solely focused on,” Kirby said. “It’s truly sort of a global look.”

So far, about 2,500 Afghan personnel have worked through the special immigrant visa process, with about half indicating a “willingness to move at this point,” Kirby said. The process is State Department-led and would likely use chartered flights to fly the personnel out of the country. The military does have “transportation capabilities” that could be used, but it appears unlikely airlift would be required.

Biden reiterated the U.S. military’s plan to maintain an “over the horizon” presence to conduct counterterrorism operations, though no specifics have been announced, and it’s not clear what nearby nations would host a continued American footprint. The “over the horizon” capability will “allow us to keep our eyes firmly fixed and act quickly and decisively if needed,” he said.

Kirby said the military plans to use “a range of [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] capabilities at our disposal” to keep watch over Afghanistan while also leveraging the “strong relationship” with Afghan forces who are continuing to fight on the ground.

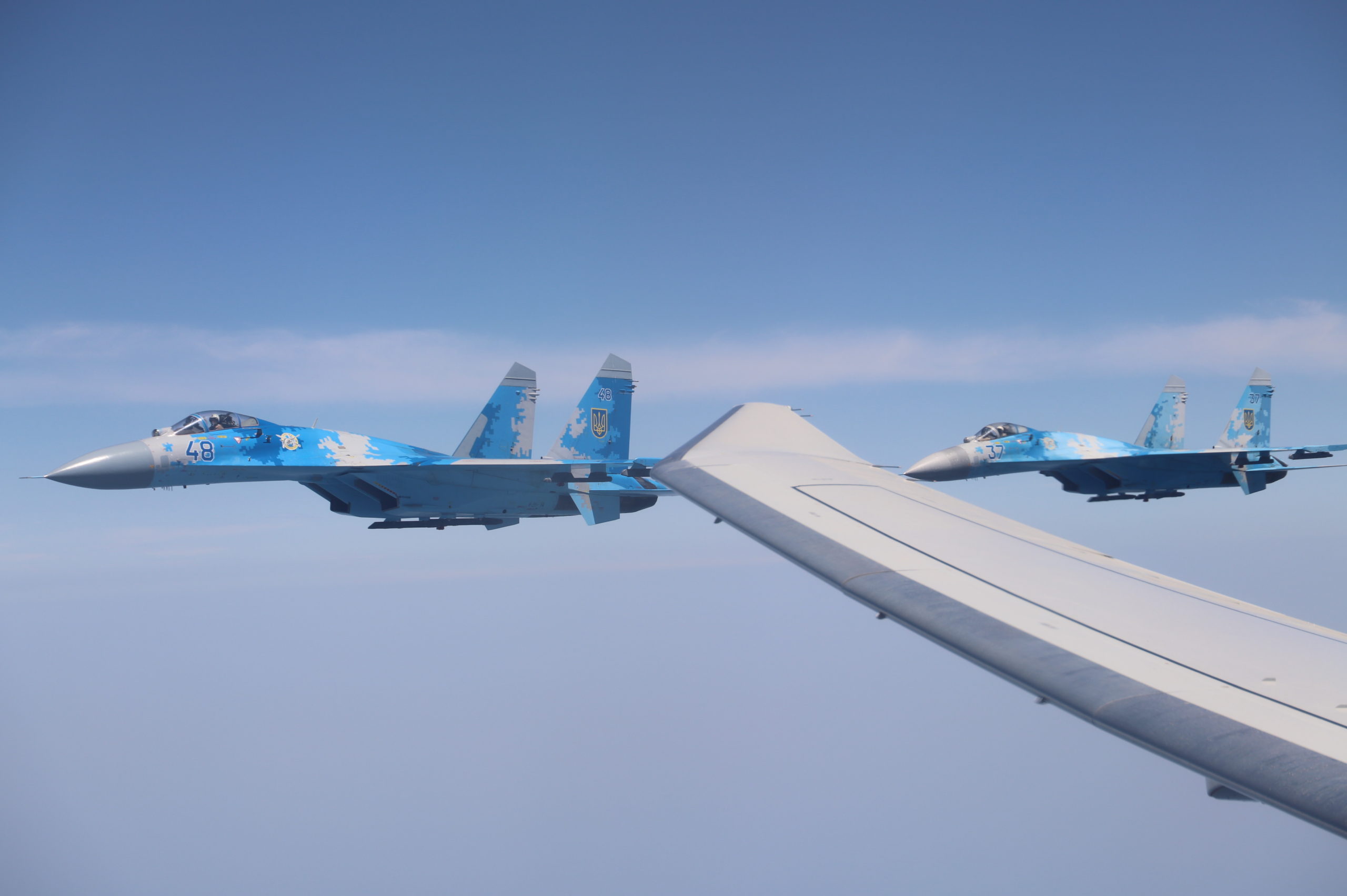

The military is still figuring out how it will support the Afghan Air Force from outside the country while it’s also continuing to send more aircraft to the country. This includes two refurbished UH-60 Black Hawks with several more on the way, along with maintaining AAF Mi-17 helicopters, and three more A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft, Kirby said.

American forces over the past 20 years, “through great blood and treasure,” built up the Afghan National Self Defense Forces with aircraft, modern weaponry, and the training to use them, but the question remains: “Are they going to use that capacity?” Kirby said.

The U.S. mission in Afghanistan, to bring Osama bin Laden “to the gates of hell” and to prevent al-Qaida from being able to plan and launch attacks targeting the American homeland, had long been accomplished, Biden said, noting the withdrawal is long overdue. There is now no way to win the war militarily. Instead, a negotiated settlement is required.

“We did not go to Afghanistan to nation-build,” Biden said. “It is the right and the responsibility of the Afghan people alone to decide their future.”

Lawmakers React

On Capitol Hill, lawmakers shared mixed reactions on the announcement of ending America’s longest war.

House Armed Services Committee Chairman Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) said in a statement that it was a “critical step” to ending the conflict and that “certain problems” lack a purely military solution.

“It is now up to the Afghan people to decide their future as they continue to grapple with their ongoing civil war,” Smith said. “The Taliban poses a real threat to stability, but the Afghan National Security Forces are highly capable.”

Rep. Mike Waltz (R-Fla.), a former Green Beret who sits on the HASC, said he is encouraged to see the administration “finally begin to focus on evacuating Afghan interpreters, … but I fear time has run out” following a rushed withdrawal.

“Thousands of Afghan interpreters and their families eagerly await their fate while the clock ticks,” Waltz said. “As the Taliban continue to gain strength and ground, they are hunting down those who stood with America in our fight against global terror.”

Senate Armed Services Committee member Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) said in a statement that Biden may have “set a deadline to end the war,” but al-Qaida and ISIS “don’t have deadlines when it comes to attacking American interests.” He warned that conditions are developing in the country for a re-emergence of those groups.