A KC-46A tanker from McConnell Air Force Base, Kan., suffered a mishap while refueling an F-15 Eagle on Aug. 21, prompting the crews on the Pegasus to declare an in-flight emergency for its boom, according to multiple statements released by units involved.

No one was injured during the incident, but the 931st Air Refueling Wing that operated the KC-46 did say in a release that the aircraft landed with its boom down at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., and dropped a “portion” of the boom nearby the base.

Unconfirmed photos claiming to show the KC-46 after it landed circulated on the unofficial “Air Force amn/nco/snco” Facebook page—in the photos, the boom appears to have broken in half, with exposed wires and pipes, and the exhaust cone of the tanker is badly damaged.

The 931st Air Refueling Wing could not confirm the pictures’ veracity.

An investigation is underway to find out the cause of the mishap and details of the damage to both the KC-46 and the F-15, the wing’s statement added. The wing wasn’t immediately available to provide further information on which unit the fighter belongs to or where it landed following the incident.

The Travis runway temporarily closed to allow personnel to respond to the aircraft and ensure the crew’s safety but has since resumed normal operations, the 60th Air Mobility Wing said in a separate statement.

“Our Airmen are not only primed to respond at a moment’s notice, they are also capable of navigating and preventing further danger during an emergency,” Col. Cynthia Welch, 931st Air Refueling Wing commander, said in the statement. “The KC-46 continues to provide our Team McConnell aircrews with precise opportunities for air refueling, cargo and aeromedical supporting are partners here and worldwide.”

While the cause of the mishap remains unclear, the tanker aircraft has been plagued by problems with its refueling system and suffered multiple refueling accidents over the years. This latest incident is the second mishap within two months involving the McConnell AFB; in June, one of its tankers was damaged while refueling a USAF F-16 in Dutch airspace. Audio from the aircraft described a refueling door damage on the fighter due to a “too close breakaway incident” between the two aircraft. An Airman aboard KC-46 then reported the tanker was also “damaged and unable to refuel.” The cause of the mishap is still under investigation.

Another midair refueling incident in 2022 left a Pegasus heavily damaged after it attempted to gas up an F-15. Unconfirmed photos posted on social media website following the accident showed a wrecked boom of the plane below its dented tail cone.

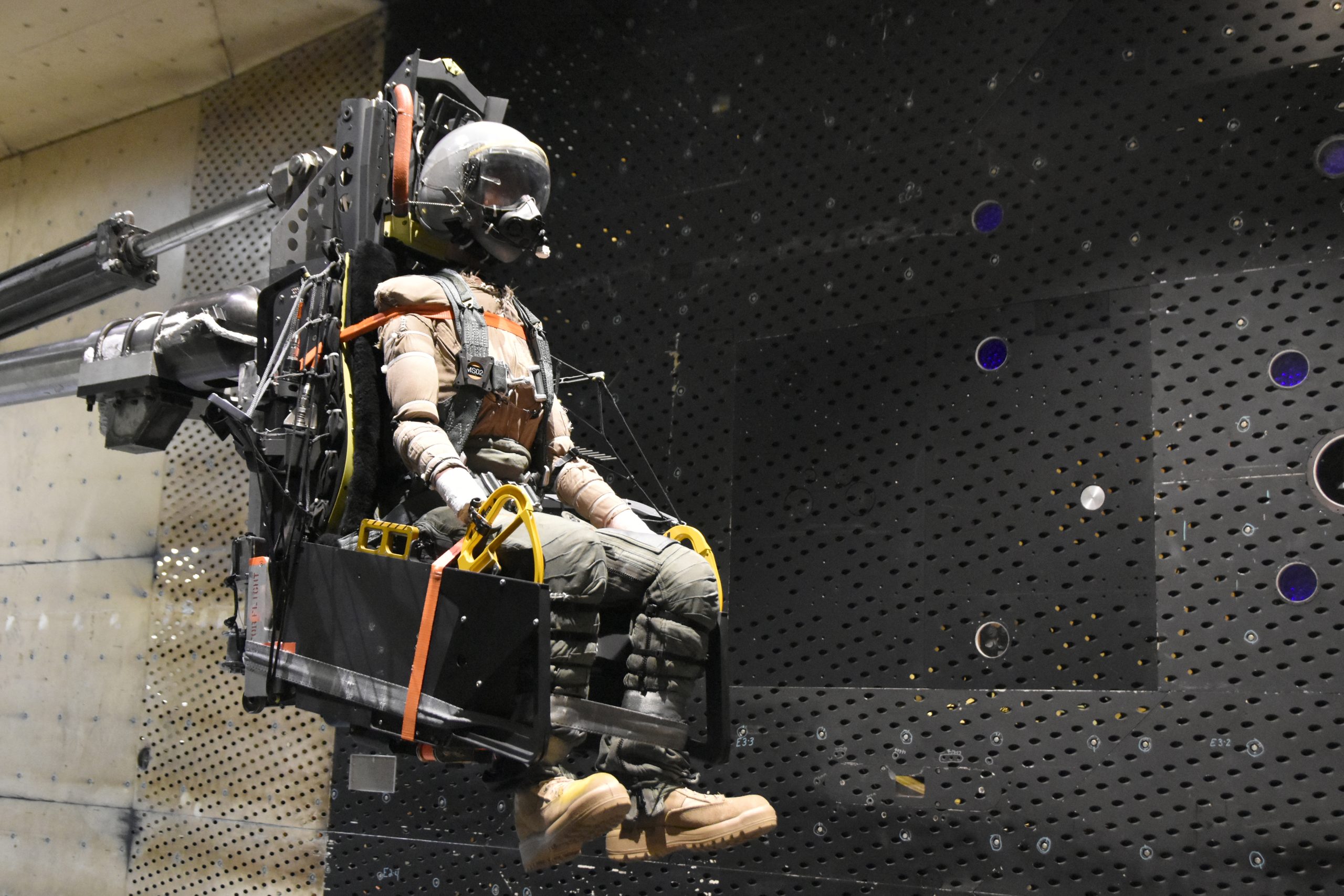

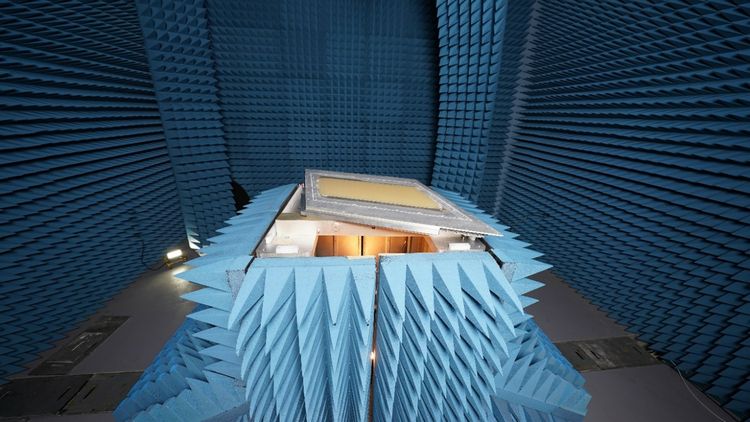

The Air Force and Boeing are currently working to resolve multiple Category I deficiencies to the KC-46’s refueling system, including a “stiff” boom and a faulty Remote Vision System (RVS), a setup of cameras and monitors the boom operator uses to connect the tanker to the refueling aircraft. The system washes out or blacks out in certain conditions, such as in direct sunlight. The RVS system can also cause issues with boom operator’s depth perception, which creates the risk of the boom operator accidentally hitting the aircraft the KC-46 is refueling.

Fixes for both the stiff boom and the Remote Vision System are still months, if not years, away. In the meantime, Travis is making the transition from the KC-10 to the KC-46—becoming the last base to say goodbye to the Extender.