A government watchdog said the Air Force’s proposal to divest 32 of its oldest F-22 fighter jets leaves too many questions unanswered for Congress to make a well-informed decision.

Specifically, the service needs to provide better information about what toll the divestments would take on the F-22 program’s ability to train pilots, test new capabilities, and meet mission requirements, the Government Accountability Office wrote in a June 18 report. The service also needs more analysis on the costs of maintaining the current fleet and of possibly upgrading the 32 jets in question.

“We respect the Air Force’s need to make difficult budget decisions in the face of limited resources and having to provide the necessary tools to the warfighter,” GAO officials wrote. “This does not, however, alleviate it of the responsibility to document the process and data it uses to make these decisions.”

The Air Force currently has 185 F-22s—150 in the Block 30/35 configuration, 33 in the Block 20 configuration. Block 30/35 includes upgraded radar, weapons, and communication, enhanced GPS systems, and improved cockpit and heads-up displays. The Block 30/35 jets also have better air-to-ground attack capability and can fire modern AIM-9X and AIM-120D missiles.

Lagging farther behind are the Block 20 jets, which are used primarily for training new pilots. Air Combat Command officials said new F-22 pilots spend 90 percent of their initial flight training on Block 20s, but the Air Force thinks the Block 20s are not worth the cost of maintenance as the service looks to modernize.

Wear and Tear

One modernization effort is the Next-Generation Air Dominance program, a family of systems that are supposed to replace the F-22 as America’s ace-in-the-hole for air-to-air combat. The Air Force thinks it would save about $1.8 billion for programs like NGAD between fiscal years 2024 and 2028 by divesting the Block 20 F-22s, but GAO says the service has not done its homework checking those calculations.

Small as it is, the F-22 fleet did not meet its mission capability or aircraft availability goals in any fiscal year from 2011 to 2021. In fact, most F-22 combat squadrons have 24 Block 30/35 jets to make sure there are 12 mission capable aircraft at any time. If the Air Force transferred 32 Block 30/35 jets to training squadrons, it would leave just 18 total aircraft at each combat unit, the report noted.

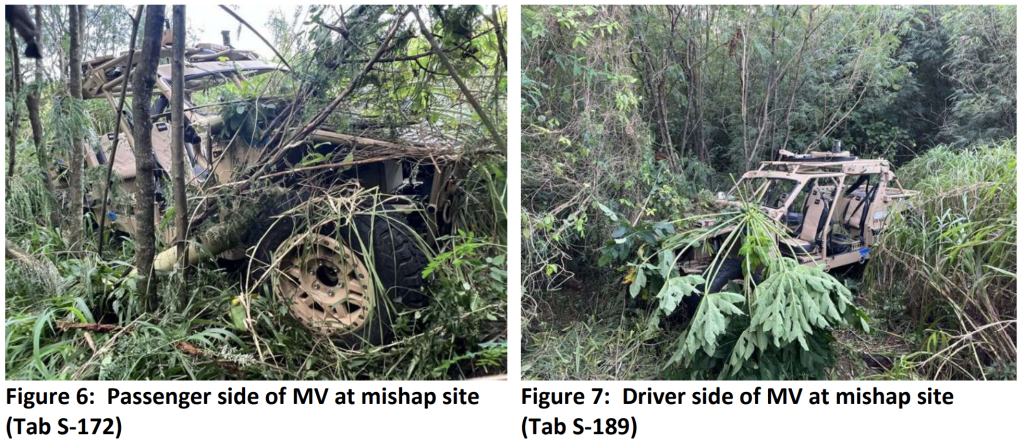

“This would increase the wear and tear on these aircraft since, according to Air Combat Command officials, new pilots often have hard landings and make other mistakes that are tough on aircraft,” the watchdog agency explained.

It is also unclear how long the F-22 fleet would have to sustain that tempo, since there is no publicly available date for when NGAD could take the Raptor’s place. Indeed, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin said last week that NGAD faces an uncertain future amid the service’s competing modernization priorities.

Even if the Air Force published a date tomorrow, there could still be years of delays similar to the ones that have befallen the F-35 fighter and T-7A trainer, GAO noted. Divesting the Block 20s could also cramp F-22 developmental and operational testing programs, which are already under-resourced, the report added. The watchdog argued that Congress could make a more-informed decision if the Air Force’s calculations were sound, but those are not publicly available.

“Materials supporting the Air Force’s divestment decision stated that these issues, along with their associated risks, required further analysis,” GAO noted. “We were not provided documentation that these issues were analyzed.”

Some of that may be due to current Air Force budget guidance, which “does not require the Air Force to provide key information to Congress regarding divestment decisions,” the GAO found.

Upgrades?

The Air Force argues that the Block 20s are too outdated to fight a war against China, but GAO noted that the service did not adequately explore the idea of upgrading the jets to the Block 30/35 configuration. Prime contractor Lockheed Martin estimated it would cost at least $3.3 billion and at least 15 years, largely due to the time and cost of restarting parts production lines. The price tag would work out to at least $100 million per tail, more than the cost of a brand-new F-35.

Lockheed Martin told GAO the upgrade cost estimates were not submitted in response to a formal request for proposal by the Air Force and should be considered notional. Neither the Air Force or contractor looked into upgrading the Block 20s with other parts from active production lines or achieving some other configuration besides Block 20 and Block 30/35.

“Because the Air Force did not fully assess its options to upgrade, the Air Force and congressional decision makers have limited insight about the potential consequences of Block 20 upgrades and are not well-positioned to make informed determinations about the future of these aircraft,” the watchdog wrote.

After the Air Force proposed divesting Block 20 F-22s in its fiscal year 2023 budget proposal, Congress included language in that year’s defense bill prohibiting the service from divesting the jets until fiscal year 2028 so that more information could be gathered, including GAO’s report.

Earlier this year, both the House and Senate Armed Services Committees blocked the Air Force’s proposal to retire 32 F-22s in their markups of the fiscal 2025 National Defense Authorization bill.

The Senate also directed the Air Force to provide “an annual report on the Air Force tactical fighter force structure” and work with the Navy to develop a plan for air superiority in the 2030s and ‘40s.

The pause could give the Air Force more time to explore the costs of upgrading or divesting its Block 20 F-22s. The GAO said the service did not agree with its recommendations to fully document the options for divesting and upgrading, but it encouraged Congress to consider requiring the Air Force provide such data before making divestment decisions.

The Navy already has a similar program requiring the Navy Secretary to submit a detailed rationale and exploration of options to Congress in order to decommission or inactivate a battle force ship before the end of its expected service life, GAO pointed out.

“Without guidance, the Air Force may continue to make budget proposals to Congress that include divesting assets without documenting the impact of these decisions on its entire fleet,” the watchdog added.