While the Air Force is in the midst of a push to modernize its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms, it’s the Space Force that could wind up taking on more ISR missions in the years ahead, Undersecretary of the Air Force Gina Ortiz Jones hinted Nov. 30.

Speaking during an Air Force Association Air and Space Warfighters in Action symposium, Jones was asked about the Department of the Air Force’s vision for the future of ISR. In response, she pointed to the USSF.

“When we think about ISR, I think what’s important is ensuring that we are thinking … not just from the Air Force perspective, but also from the Space Force perspective,” Jones said. There are many things that just make a lot of sense to do from space, in the interest of resiliency, in the interest of capability. And so [it’s about] ensuring that there’s a right balance there.”

As Air Force leaders increasingly emphasize strategic competition with China, an emphasis has been on acquiring and fielding platforms that will be better equipped for a high-end fight.

This led to the Air Force requesting to cut back on ISR operations in its fiscal 2022 budget, specifically by the MQ-9 Reaper drone. The service has also sought to retire its E-8C Joint STARS fleet. The intent behind these moves, leaders said, is to free up money for modernization efforts, such as making the MQ-9 more survivable in contested areas and further developing the Advanced Battle Management System, an ambitious effort to connect sensors and shooters using advanced technology and artificial intelligence.

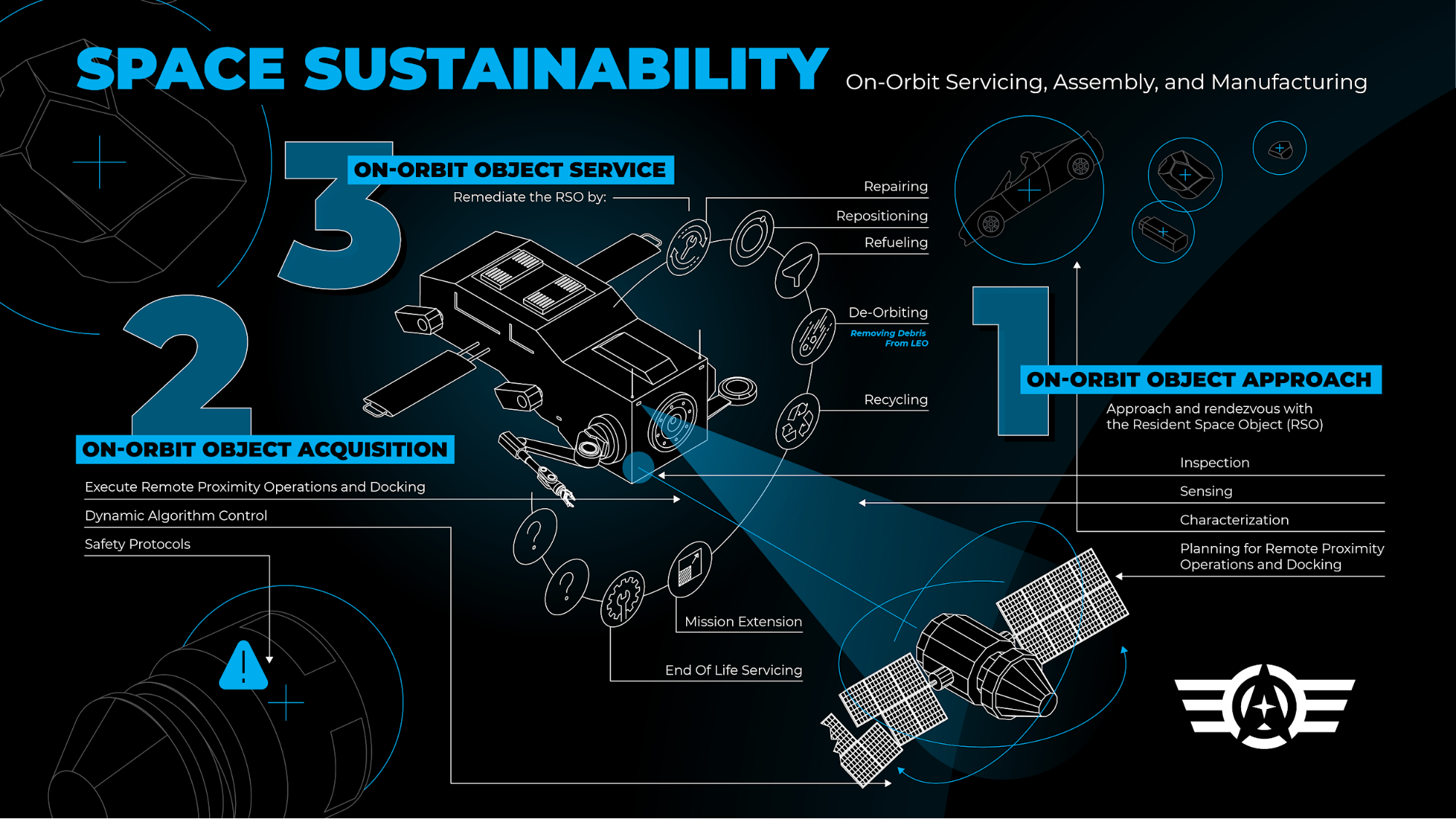

The Space Development Agency, meanwhile, is in the midst of an effort to build out the National Defense Space Architecture, a constellation of satellites that will be used for tracking targets as well as missile warning, communications, data coverage and sharing, and other capabilities.

The first layer of the NDSA is the Transport Layer, aimed at ensuring data and connectivity across the globe. Tranche 0 of that layer is expected to launch by March 31, 2023, with Space Development Agency Director Derek M. Tournear saying he hopes to roll out new capabilities every two years.

“If you hear [Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall] talk about our space architecture, it’s one of our strategic advantages, but we’ve got to make sure it continues to be that and how we [might] identify some opportunities in the ISR domain … in the space realm,” Jones said.

The Space Force, for its part, has already expressed an interest in the ISR mission. Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond said back in May that the service will get involved in providing tactical ISR, normally the realm of the Intelligence Community. The proliferation of small satellites and the dropping cost of launches made such a move possible, Raymond said, and it is “complementary” to the service’s existing missions.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified the agency responsible for building out the National Defense Space Architecture. The Space Development Agency is responsible for procuring satellites for the NDSA.