Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III insisted he “never intended” to keep his hospitalization following complications from prostate cancer surgery a secret amid grilling from lawmakers over his failure to notify the White House, Congress, and the public of his medical situation, despite having to transfer his authorities.

“I never told anyone not to inform the president, the White House, or anyone else about my hospitalization,” Austin told the House Armed Services Committee on Feb. 29.

In a heated two-hour hearing Austin was repeatedly pressed on why, as the official in charge of the U.S. military, its nearly $1 trillion budget, and two million military personnel, Austin did not let the White House know of his absence for four days after his Jan. 1 admission to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. It wasn’t until Jan. 9 that the White House, Congress, and the public found out the cause of Austin’s hospitalization stemmed from surgery for prostate cancer Austin had on Dec. 22.

“I find it very concerning that the secretary could be hospitalized for three days without anyone else in the administration even noticing,” HASC chairman Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) said.

Lawmakers’ questions were also focused on what others in the Department of Defense knew and when. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks was on vacation in Puerto Rico during the incident, but while Hicks was effectively running the Department of Defense, she was not told of Austin’s condition. Lawmakers asked Austin why the decision was made to keep details of his condition under wraps while he was in intensive care, though Austin said he was not sure.

“I would emphasize that there was never a break in command and control,” Austin said. “We transferred authorities in a timely fashion. What we didn’t do well was a notification of senior leaders.”

The Pentagon conducted a 30-day review of the incident and released an unclassified summary, but that document largely ascribed the situation to well-meaning officials making decisions that in hindsight led to President Biden and other top leaders being unaware that the Pentagon chief was unable to perform his duties for several days due to medical issues.

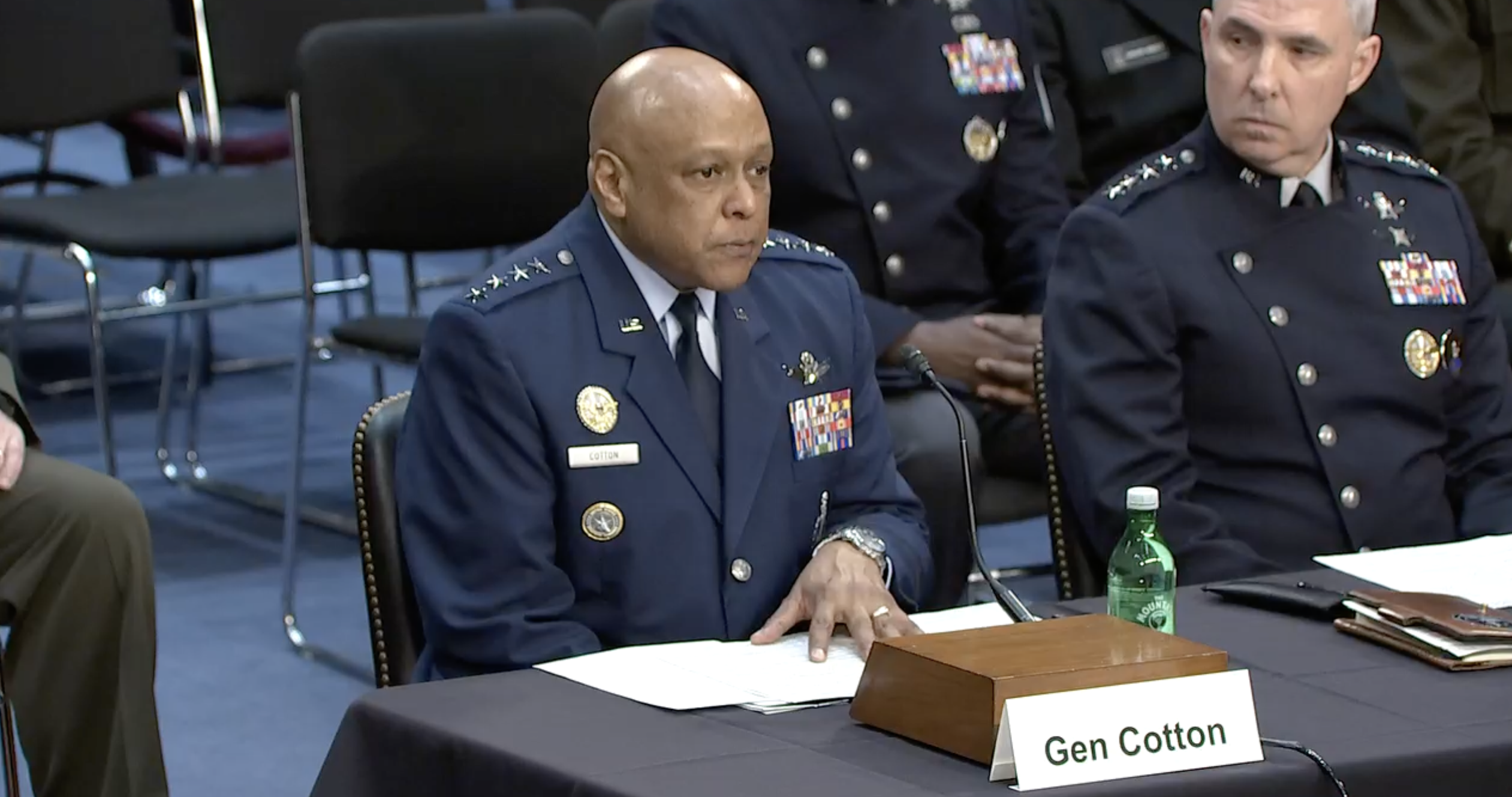

Austin said on Feb. 29 that Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. knew on Jan. 2 of his hospitalization. Earlier, the Pentagon disclosed a handful of key staff including Chief of Staff Kelly Magsamen and Pentagon Press Secretary Air Force Maj. Gen. Patrick S. Ryder knew on Jan. 2 as well. The White House and Biden found out Austin was in the hospital on Jan. 4, and Congress and the public—including most of the Pentagon—were not notified until Jan. 5.

“I would expect that my organization would do the right things to notify senior leaders if I am the patient in the hospital,” Austin said.

However, his aides did not make those notifications. While the internal 30-day review shed little light on the situation, there is also a Defense Department inspector general investigation occurring. The Senate Armed Services Committee received a classified briefing from the DOD on Feb. 27.

“I’m not going to provide a minute-by-minute tick-tock,” Ryder told reporters later on Feb. 29. “When the secretary was admitted into the critical care unit, it became clear that he would not have access to his secure communications, so following the procedures that his aides have followed in the past when he has not been able to access secure communications the decision was made to initiate the transfer of authority to the deputy secretary. And that process played itself out.”

But details of that process are opaque. The DOD report is mostly classified. The public portion says there was “no indication of ill intent or an attempt to obfuscate” by Pentagon staff.

“I take full responsibility for this,” Austin said. “We didn’t get this right.”

In his testimony, Austin said he did not know why his staff was not proactive, but he did not believe they were trying to “willingly conceal something.”

“Recognizing and looking back through all of this, through the review process, probably the improvements could be made,” Ryder said. “We’re undertaking those process and procedure improvements.”