When China’s air force and coast guard engaged recently in apparently provocative actions in the East and South China Seas, most Western media framed the events as evidence of Beijing’s aggressive and potentially destabilizing behavior. While aggressive is often an apt term for People’s Liberation Army (PLA) operations, important details and context are often overlooked.

The PLA’s rapid growth and expansion, combined with its relative lack of experience, poses outsized risks—especially if Beijing is directing the PLA to provoke interactions with U.S. allies and partners.

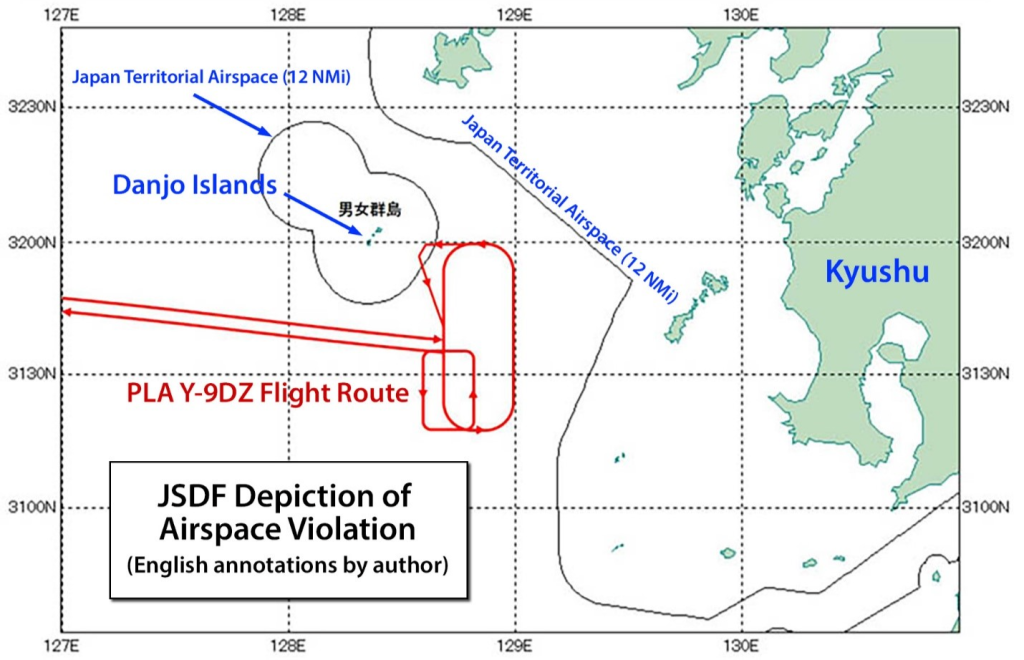

Japanese officials responded angrily this week when a Chinese military aircraft entered Japanese airspace, calling the incident an “utterly unacceptable” incursion. On Aug. 26, a PLA Y-9DZ electronic intelligence collection aircraft came within 12 nautical miles of Japan’s Danjo Islands, 80 miles west of Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island. It was the first time a PLA aircraft had violated sovereign Japanese airspace since the Japanese Self Defense Force started keeping records of such events in 1967.

(Source: Japan Ministry of Defense)

While there is no doubt this incident was a violation of international law, it is not clear it posed a serious threat to Japan’s security. The Y-9DZ, among the newest of the PLA’s special mission aircraft, was flying directly at the small outcropping of Japanese islands when it penetrated Japanese airspace for about three minutes. However, the windswept Danjo Islands are both uninhabited and undefended. The islands’ main purpose seems to be as an anchor for a marine sanctuary and nesting grounds for a vulnerable species of Japanese sea bird. Unlike the disputed Senkaku Islands, China makes no claim to these rocky spits of land. In response to Japanese protests over the incident, China’s foreign ministry spokesman said China has “no intention” of violating any airspace.

While it is certainly possible the airspace violation was unintentional, there is still cause for concern. China’s defense contractors began mass producing special mission aircraft for the PLA in 2019. Over the past several years, increasing numbers of these aircraft have appeared at PLA air bases, which have made upgrades to base infrastructure to accommodate the new aircraft. The rapid influx of new reconnaissance aircraft necessarily means many aircrew are likely inexperienced with little flight time in their new aircraft. Because these aircraft are increasingly being sent on flights where they will encounter a U.S. or allied response, tense situations will inevitably ensue where experienced aircrew and cool heads would be preferred.

If the airspace breech was intentional, however, it is entirely possible that Beijing manufactured the violation as a distraction for this week’s visit to Beijing by U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan. The two days of meetings on Aug. 27-28 were the first visit by a U.S. national security advisor to China in over eight years. Sullivan and his Chinese counterparts discussed many important topics, from Chinese protests over U.S. support for Taiwan to cooperation on counternarcotics to guardrails for the military use of artificial intelligence. Agendas for these types of high-level meetings are often set weeks in advance with outcomes all but predetermined.

One of Beijing’s well-known, if unacknowledged, negotiating tactics is to create an incident immediately in advance of or during a high-level diplomatic visit. The Chinese side is completely prepared for the incident, but the event upsets the established agenda and drives unprepared foreign participants to focus on the manufactured crisis. There is every reason to believe both the unprecedented violation of Japanese airspace and the past week’s escalating incidents involving the Philippine and Chinese coast guards were intended to shape the information space to Beijing’s advantage during this week’s high-level talks.

The PLA will continue to drive regional tensions which, intentionally or unintentionally, could draw the U.S. military into a conflict in East Asia. Relatively inexperienced PLA personnel operating new ships and aircraft in close proximity to U.S. and allied military forces in unfamiliar operating areas pose a significant concern.

That Beijing might direct Chinese military forces to intentionally create an incident to further a strategic narrative is a very dangerous game indeed. In increasingly crowded airspace and water space, a military crisis that happens quite by accident seems much more likely than a deliberately executed PLA operation.

Beyond the attention-grabbing headlines heralding Chinese military aggression, the details and context surrounding these military and security events should be clearly understood to reveal Beijing’s strategies and the potential dangers inherent in their execution.

J. Michael Dahm is the Senior Resident Fellow for Aerospace and China Studies at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. He previously served as a U.S. naval attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, China.