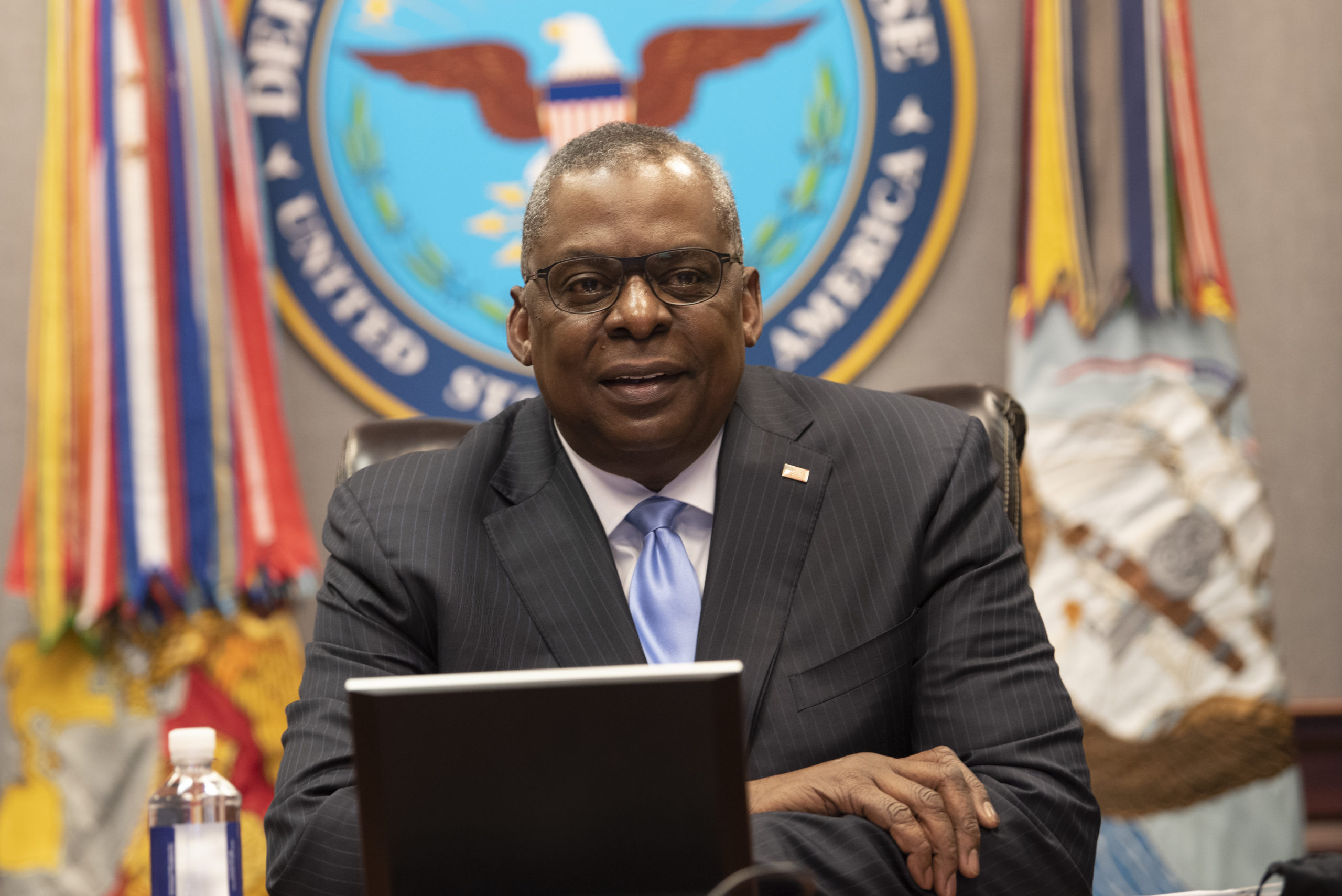

Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III has tested negative after experiencing mild symptoms during a bout with the COVID-19 virus. Austin returned to the Pentagon on Jan. 10 after completing an at-home quarantine during which he continued to work remotely.

“The Secretary has tested negative for COVID today and will return to the office tomorrow,” Pentagon Press Secretary John F. Kirby said in a statement Jan. 9.

Austin last met with his staff at the Pentagon on Dec. 30 before going on leave. Kirby confirmed that no more senior Pentagon leaders had tested positive for the virus.

“Secretary Austin is grateful for efficacy of the vaccines he was administered. He knows that they rendered much less severe the effects of the virus,” Kirby added.

Austin’s COVID-19 condition was first made public after a positive test Jan. 2. The Secretary’s return to in-person work occurs on the ninth day since his symptoms began the evening of Jan. 1.

Revised Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations advise those testing positive for COVID-19 to isolate at home for five days and wear a mask for an additional five days.

Kirby said Austin will continue to follow CDC guidelines as well as the Pentagon’s Health Protection Condition (HPCON) Charlie protocols, which were put back into place Jan. 6. The Pentagon lowered its HPCON level to Bravo in 2021, briefly lifting a mask mandate until a surge of the delta variant prompted the return of universal mask-wearing in the building.

The increased Pentagon restrictions were reimposed because of the “extremely high rate of new cases and positive test results” in the Washington, D.C., area. The restrictions that began Jan. 10 included maximum telework and flexible scheduling to allow for an occupancy rate of 25 percent; mask-wearing indoors; six feet of physical distancing; and meetings limited to fewer than 10 people.

Austin maintained “the same battle rhythm” he had while working from the building during his at-home quarantine, including participation in a virtual summit with Japan alongside Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Kirby said Jan. 4.

As of Jan. 5, 1.6 million service members were fully vaccinated and 336,000 were partially vaccinated against the coronavirus. Of the 273,724 total Defense Department cases so far, 86 service members have died from the disease, while 2,333 service members remain hospitalized. The Department of the Air Force has tallied 49,423 COVID-19 cases to date. The department required all Active-duty members to be fully vaccinated by Nov. 2, 2021, while the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve had until Dec. 2, 2021, to become fully vaccinated.