While it’s probably too late to fix the supply and trustworthiness of the current global microelectronics enterprise, there’s good reason to think the U.S., especially with some government investment, can regain its edge as a world chip supplier, experts said during a virtual Hudson Institute seminar Aug. 23.

There is a world shortage of microprocessor—”chips”—leading to supply delays for everything from cars to weapon systems, and many of these devices are afflicted by insecure features making them vulnerable to manipulation. The Pentagon is concerned that these vulnerabilities could be exploited by an adversary, either for espionage or to render them inoperative in combat.

“What we need, honestly, is a goal,” set by American policymakers about how the U.S. can remain the leader in the next generation of chip design and manufacture, said Victoria Coleman, Air Force chief scientist. The U.S. is poised to exploit “leap ahead” technologies in “fabrics, … materials, … and devices,” and targeted, “mindful” government investment can help set the stage for re-establishing the U.S. as the world leader in this area, she said.

“It’s also about creating a framework that can take those investments, prove them out, scale them, and then build sustainable business models around them,” Clarke said. It may require changes to regulation, government investment, or joint government/private investment.

“Policymakers have a lot of tools in the toolkit” to do this, she said, but it’s important to set goals so “we know … we’ve won.” However, due to the cost of labor, “it’s not possible to pull us out of the hole that we find ourselves in today with respect to leading-edge manufacturing of semiconductors,” she added.

Jay Goldberg, chief executive officer of D2D advisory, said when it comes to manufacturing and the current U.S, dependence on global chip supply networks, “that battle’s over.”

“Let’s look to the future,” he said. While China has done an excellent job revving up its design capacity, its efforts at production are focused on obsolescing generations of chips.

“China has done a pretty good job of incentivizing their industry to work together,” he said, “but they’re really building something for the last century. Just like Stalin in the ‘50s built railroads and hydroelectric dams, … the best 19th century economy in the 20th century.”

The U.S. doesn’t need to “invest in design, there’s all kinds of new fields coming up … That’s where we should focus. That’s where we’ve done well in the past and we’ll continue to do well in the future,” Goldberg said.

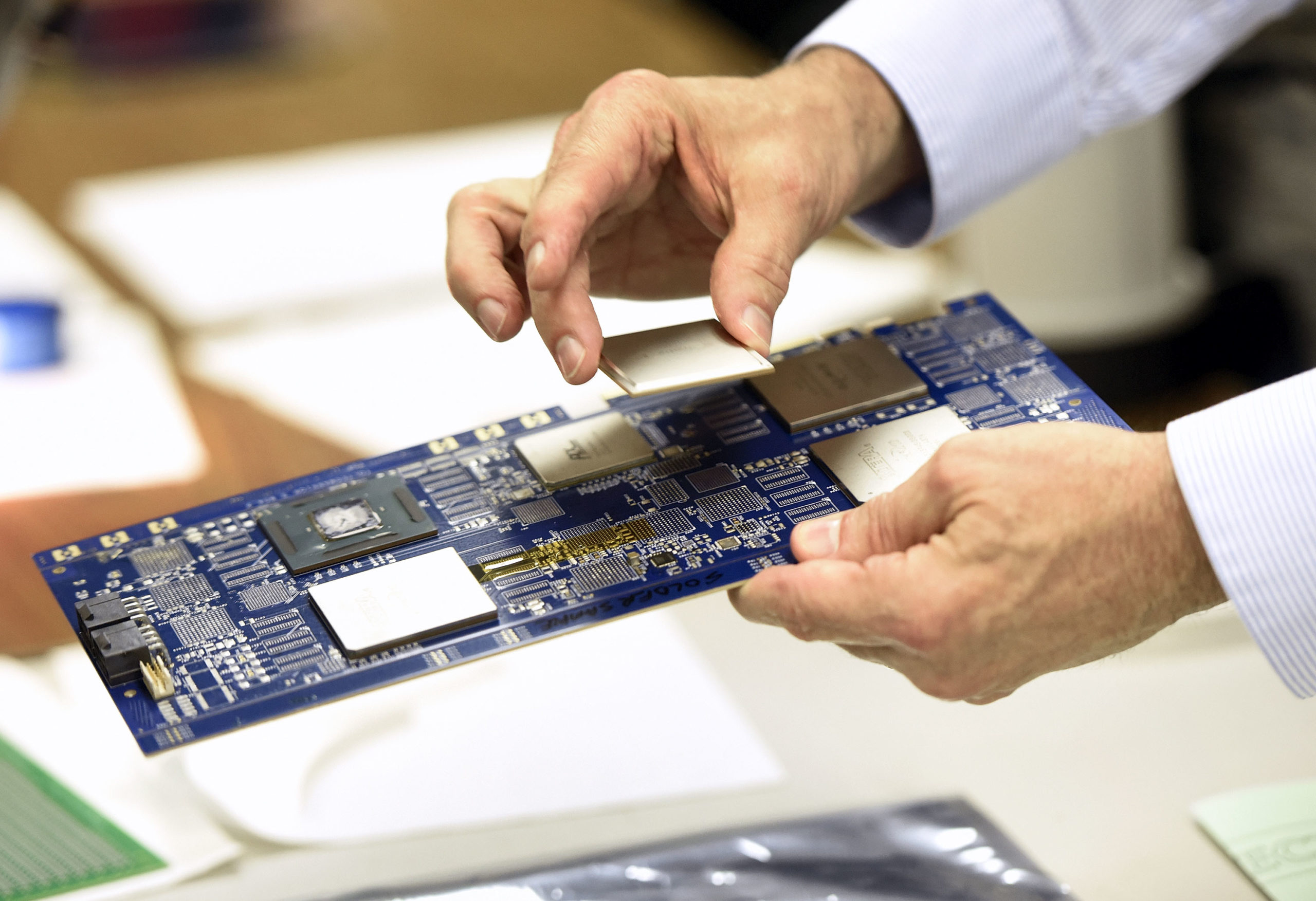

Bryan Clark of the Hudson Institute, who co-authored a recent paper on the topic, “Regaining the Digital Advantage,” said the U.S. is best suited to the design and packaging aspects of the microelectronics enterprise; less so in manufacture because of the labor cost differential with Asia.

“How do we make sure we’re able to support the demands of future customers? You’ve got to be positioned in the parts of the supply chain,” he said. “Fabrication may not change that much between current generation chips and fifth-generation chips. But designs will change dramatically; packaging could change dramatically” because new chips or “triplets” will have new and potentially “heterogeneous” designs. The U.S. will be “well positioned” because it can “add value for the future, even if it’s not well positioned to support current demand” due to the low level of fabrication capacity in the U.S.

Still, government could “provide incentives to close that cost differential and make U.S. chips competitive,” he said.

Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D-N.J.), a member of the House Armed Services Committee and the Defense Supply Chain Task Force, said future technologies such as “system on a chip, … heterogeneous or … disaggregated chip architecture,” will create opportunities to “bring … home” microelectronics dominance, and these are the areas government may seek to invest in. She advocated for more “pure science” research and development, along the model of Bell Labs in the 1950s and 1960s.

There are many years of work to be done fixing “vulnerabilities” in existing chips; some that were created inadvertently to get things to work, and some “nefarious,” created by overseas manufacturers with “evil intent,” Clarke said.

“We have our work cut out for us,” in that regard, she said, noting she is “very excited” about “zero trust” architecture design because “there will continue to be both intentional and non-intentional flaws in devices … Let’s build them in such a way that they’re actually resilient … When [faults] hit us, we can contain the infection, … so that it doesn’t spread to the whole system, so we can fail safely … It’s about how you build systematic resilience.”