Engine makers should be able to meet House defense policy bill language calling for a new F-35 powerplant based on the Adaptive Engine Transition Program by 2027, but only for the conventional takeoff versions, a GE Aviation executive said.

“We would be eager to step up to the challenge to meet the 2027 deadline” that the House version of the National Defense Authorization Act included, David Tweedie, general manager for advanced combat systems at GE Aviation, said in a Sept. 10 interview, adding that doing so is “certainly within the art of the possible.”

He said, “We were encouraged by both the direction [to the Joint Program Office] to provide a transition plan, as well as authorization for an additional $257 million of funding above the President’s Budget request, so we are encouraged on all those counts.”

After $4 billion in investment by the Air Force, through several successive technology programs, GE is in the final stages of testing its XA100 engine and Pratt & Whitney is also testing its XA101. The AETP program is a risk-reduction effort designed to make sure the technology is available if the Air Force wants to move on to a new powerplant for its fighters. Tweedie said the plan was always to develop an engine that could be applied to the F-35 at midlife, and to other, future aircraft, but not as a retrofit to the F-15, F-16, or F-22. The AETP engines were “optimized to the F-35 … from the beginning,” he said.

However, the AETP engine will not be able to power the F-35B, the short takeoff/vertical landing version of the Lightning II, Tweedie said.

While “we think we have a very competitive offering for the F-35A and the F-35C, … we did not design the AETP engine to integrate with the F-35B. It was beyond the scope of what we set out to do,” he said. While Tweedie did not comment on how hard it would be to adapt AETP engines to this application, he did say it would be “beyond the budget and timeframe” set by the House to accomplish.

Pratt & Whitney, which makes the F135 engine that powers the Joint Strike Fighter, argues that putting a new engine in the jet would cost $40 billion more over the remaining expected 50-year life of the program, chiefly in sustainment costs, because of the need to develop and maintain at least two engine logistics enterprises while continuing with the F135 for the F-35B. Pratt & Whitney says it can make modifications to its F135 that would be sufficient to meet all the Joint Strike Fighter’s future power and thrust needs, with margin; and that its AETP could not be adapted to the F-35, as it “will not fit” that aircraft’s engine space.

The AETP engines were developed because the Air Force recognized that engine technology of the 1990s had gone about as far as possible, and engineers were struggling hard to squeeze even a percentage point or two more performance out of it. The AETP engines add a third airstream to the traditional turbofan cycle, giving it better thrust and providing more air for cooling, while making it more fuel efficient in cruise.

The F-35 JPO does not have an engine roadmap for integration of a new powerplant in the jet, but creating one is likely to be on the agenda of the next top-level meeting of F-35 partners and users. The JPO has not committed to using AETP technology in the fighter.

“The … AETP is in the very early stages of development and is not currently an F-35 requirement,” an F-35 JPO spokeswoman said. The Joint Program Office is “working with the AETP program office and our industry partners to evaluate this new engine technology for possible use in the F-35.”

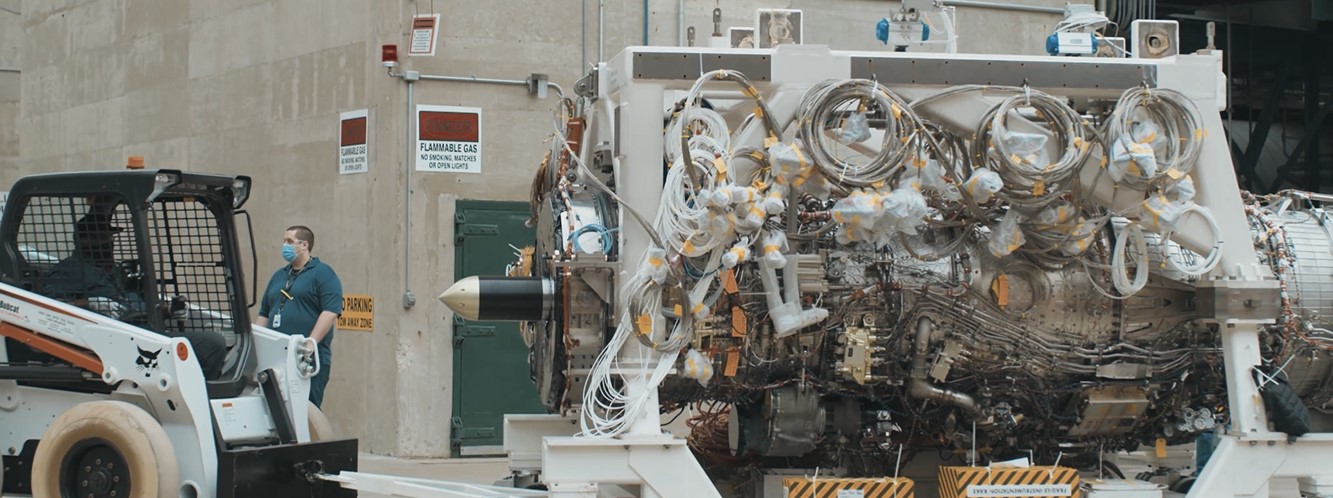

GE announced on Sept. 7 that it has begun testing the second all-up example of its XA100 AETP engine at its Evendale, Ohio, plant, which Tweedie said would likely be a “two-month effort, plus or minus.” The company says its version of the engine surpasses the F135 by 10 percent in thrust and 25 percent in fuel efficiency, along with a “significant reduction in carbon emissions.”

After GE has wrung out the XA100 at Evendale, it will be transferred to the Air Force for testing at Arnold Engineering Development Center, Tenn., where there is more sophisticated equipment that is only available to the Air Force.

It’s unclear how exactly the program will advance beyond this final stage; Tweedie said the contractors are “looking forward to what’s in the fiscal ‘23” budget request, as the 2022 version did not include out-years spending plans. “We have not seen a … finalized Air Force acquisition strategy,” he said.

But in a Sept. 7 Defense News conference, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. said it’s important to press on with it, even if it isn’t used in the F-35.

“You’ve got to continue the R&D [research and development] … so that you have options in the future,” Brown said. “If we stop the R&D on this, we basically shut ourselves off from having an option to go forward.”

GE would “need to see something in the ’23 budget to keep this momentum going,” Tweedie said of Brown’s comments, paraphrasing Brown as saying, “’You can’t stop.’ And that’s true of any major development effort. There’s a lot of cycle time lost if you bring that effort to a complete halt.”

The Air Force has had superior fighter engine technology for generations, Tweedie said, and “10 years ago, the Air Force came to industry and said, ‘We need to earn that again; we need the next generational leap in technology.” The AETP program, and other such projects before it, were focused on being “ready to go launch that next full-scale engineering and manufacturing development program … We’ve met the Air Force’s objective to burn that risk down.”

Lockheed Martin, builder of the F-35 fighter, has worked with both GE and Pratt & Whitney throughout the AETP program to ensure that what they were developing would fit in the F-35; that “access panels, and all the other things” needed for service and maintenance would line up, Tweedie said. Lockheed Martin “has been an active participant in this program from Day 1,” and the resulting powerplants should, with development, “fit seamlessly” into the jet.