Tens of thousands of Airmen, Guardians, and civilians within the Department of the Air Force reported experiencing some form of interpersonal violence that resulted “in psychological or physical harm or that detracts from a culture of dignity and respect,” according to the results of a survey released Nov. 9.

In the fall of 2020, the Air Force’s Interpersonal Violence Task Force sent out a survey that garnered some 68,000 responses, roughly 10 percent of the department. Of those 68,000, 55 percent of respondents—more than 35,000—reported experiencing some form of behavior in the past two years that the task force identified on a “Continuum of Harm.”

Those behaviors, 81 in total, included everything from physical violence to sexual harassment to workplace bullying and hazing.

“Some of the experiences are not what we would traditionally be tracking, based on the Department of the Air Force’s definition of interpersonal violence, but we want to understand what is going on, especially at that left side of the continuum, so that we can get after that,” said Brig. Gen. April D. Vogel, the Interpersonal Violence Task Force lead. “Because it is proven that when lower-level behaviors that are inappropriate are allowed to flourish, it creates an environment where worse, more egregious types of behaviors can happen.”

In a briefing with reporters, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall noted that those who responded to the survey were self-selecting, likely pointing to an over-representation of those who said they had experienced such behaviors.

“But if you only take the fact that in the 10 percent that reported, roughly half reported some type of interpersonal violence, that’s still 5 percent of the total people all by itself, which is too much,” Kendall said. “So we know we’ve got a problem to address.”

The survey also found that the majority of those who experienced interpersonal violence did not report the behavior. When asked to select the reasons they did not, a quarter of respondents said they didn’t think anything would be done, and roughly a fifth said they thought it would make things worse for themselves.

Of those who said they did report it, the majority indicated they were not satisfied with the support services provided. This stood in contrast to more than 80 percent of command team members who indicated they felt they had the “resources, training, and authority” necessary to address interpersonal violence in the chain of command.

From those findings, the task force formulated three recommendations:

- Complete a cross-functional database review to improve data awareness and sharing.

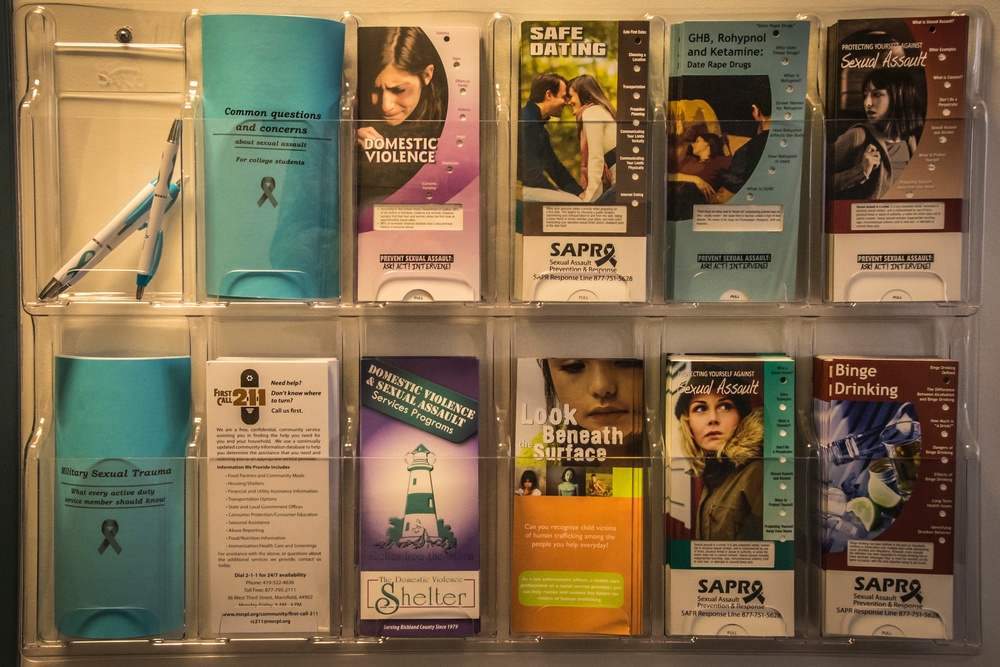

- Pursue a one-stop policy for victims of interpersonal violence.

- Establish a cross-functional team to examine barriers to reporting.

Undersecretary of the Air Force Gina Ortiz Jones has advocated for a “no wrong door” policy, with one office of primary responsibility within the department to address domestic violence, harassment, and stalking. That policy, leaders said, will be included in the one-stop policy recommendation, rather than duplicate efforts.

Intersectional Addendum

Also on Nov. 9, the Air Force released an addendum to its two previous disparity reviews. The addendum identified further disparities facing female minorities.

The most recent disparity review, released Sept. 9, found that women were generally equally represented or overrepresented when it came to promotions, enlisted leadership positions, and professional military education designations.

But the addendum, drilling down on the intersection of race and gender, found that some disparities “were basically masked or hidden by better performance of white women, for example, relative to women of color,” Kendall said.

Specifically, white women were promoted at or above the overall rate for the Active-duty force from E-5 through E-8 and O-4 through O-6 from fiscal year 2016 to 2020, with the exception of O-6 below the promotion zone, while Black women were underrepresented at E-5, E-6, and E-7; Native American women at E-5 and E-6; and Asian American woman for E-8 and E-9 promotions, as well as most officer promotions.

The disparities were particularly apparent in operations career field officers, where most Air Force leaders get their start—white men remain by far the most common group in that category, while “except for Hispanic/Latino female [company grade officers], all female minority groups had below 1 percent representation of the entire operations career fields’ force for all rank groups.” In particular, there were no Black, Asian-American, Pacific Islander, Native American, or multiracial female general officers.

Other disparities also came to light, Air Force Inspector General Lt. Gen. Sami D. Said told reporters. As an example, he cited a finding that while Black Airmen as a whole are underrepresented in wing commander positions, Black men are actually overrepresented in those leadership roles—Black women, more specifically, face the disparity.

“In this slice and dice of the addendum, you could see the disparity becoming much more pronounced at higher officer ranks on the female side of the house, and that’s critically important for the folks trying to deal with those problems instead of just aggregating male and female,” Said said.

The addendum was championed by Ortiz Jones, herself the first woman of color to hold her position within the Air Force. When the second disparity review was released, she said it “very clearly talks about some of the disparities for minorities and for women. But it’s not talking about disparities for female minorities. And when we think about having a very targeted approach to ensure that we are addressing some of the unique challenges, some of the unique barriers faced by some of our Airmen and Guardians, we have to understand the intersectional challenges that are presented.”

On Nov. 9, Ortiz Jones noted that further parsing the data meant dealing with smaller sample sizes—roughly 10 percent of Airmen and Guardians are women of color—“but given the challenges we face as a country, we’re not going to write off the experiences of 10 percent of our force.”

Said echoed those comments, saying that while the smaller groups made determining statistical significance from year to year more difficult, “when that disparity—when you look back 10 years, and it’s consistently there—that’s very meaningful.”