Commercial satellite communication providers who want to sell their services to the U.S. military will have to meet the same voluminous cybersecurity standards imposed on federal agencies themselves—plus additional ones specific to space and national security, according to a Space Force official.

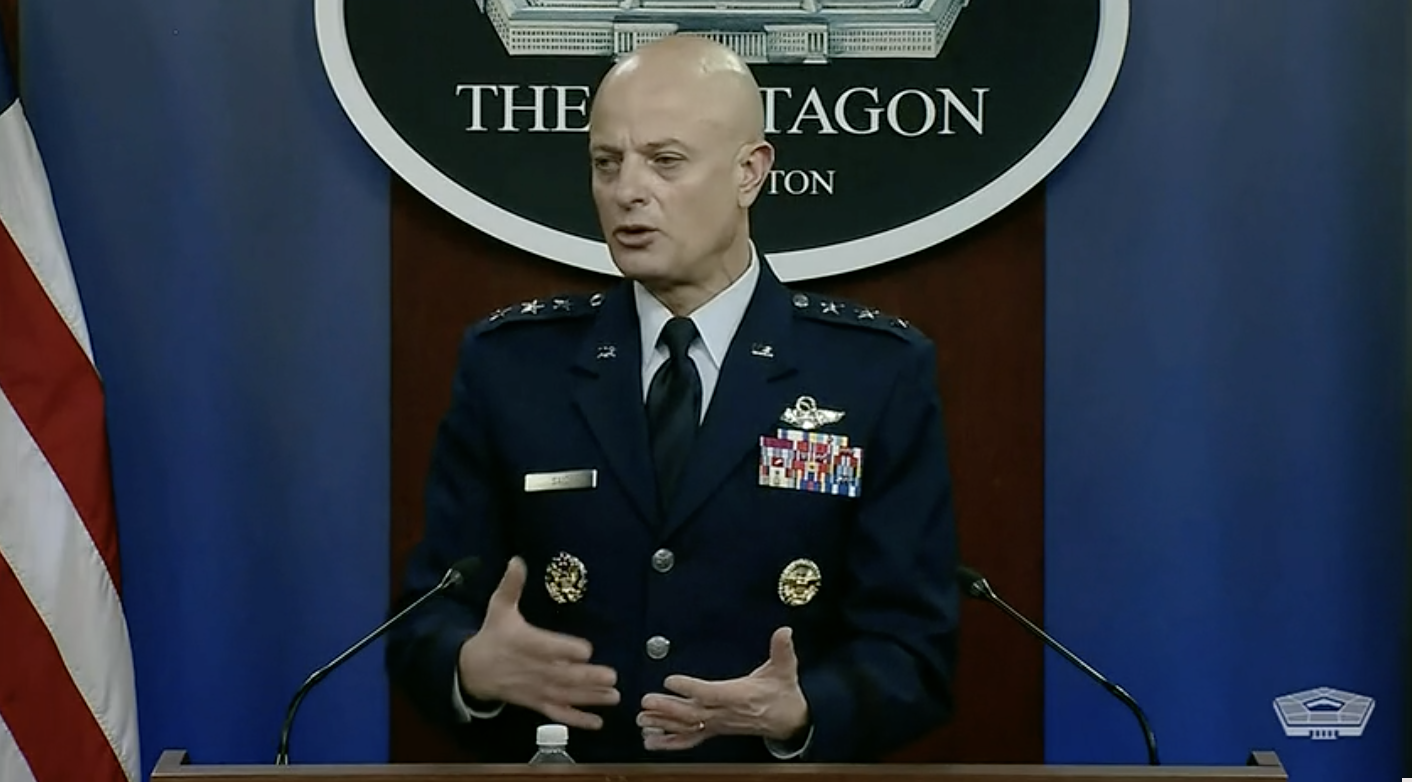

The long-delayed standards will be phased in starting next year and will be fully in place by 2025, said Jared B. Reece, the manager of the Infrastructure Asset Pre-Assessment Program, or IA-Pre, within the Space Force office that buys commercial satellite communication services for DOD.

“We wanted to implement a level playing field between the security standards for both our own [DOD] systems and our contract systems,” Reece said. So IA-Pre will require contractors to implement the IT security controls in the NIST 800-53 Risk Management Framework, just like DOD and other federal agencies must—and to use the “high impact baseline,” the most rigorous version of the standard.

NIST Special Publication 800-53 is a comprehensive catalog of over 900 security controls, broken down into 18 “families” that govern every aspect of how an IT system is operated, from ”access control” to “configuration management” and “incident response.” Additional baseline publications define the controls appropriate for the sensitivity of different systems. There will also be ”overlays”—additional or more specific control standards—designed for national security systems and space systems, Reece said in his first major interview about the program.

The move comes amid growing concern about cyberattacks on U.S. satellites that could cripple the U.S. military’s global communications network. Lt. Gen. Stephen N. Whiting, who heads Space Operations Command, predicted last year that a “cyberattack is where we are most likely to face the enemy in space.” Experts consider cyberattacks the most likely kind of military strike against satellites because they are much lower cost and typically reversible in their effects, compared to kinetic weapons.

IA-Pre, Reece explained, qualifies assets—satellites and their associated ground systems—rather than enterprises or organizations. This is important in a commercial satellite marketplace where “there are owners, operators, resellers, distribution partners, any number of assorted teaming agreements … within the industry.”

This complex marketplace meant multiple bidders might submit proposals for a single contract using the same satellite, Reece said. “We might get two companies proposing each other‘s satellites to the same [contract].”

Under the existing system, in which cybersecurity compliance is assessed during the procurement process for each bidder, acquisition officials might find themselves making multiple assessments of the cybersecurity of the same commercial satellite asset, Reece said, because it figured in contract bids from multiple vendors.

IA-Pre is designed to speed procurement by creating a kind of “approved product list” of satellite assets that have been pre-assessed as meeting the required standards, Reece said.

“Right now we’re doing a lot of duplicative work,” he explained. “Having a list of cleared assets, pre-evaluated assets, reduces all those evaluations to one: Once they’re on the asset list, they’re good to go.” Multiple vendors might bid using a single pre-evaluated asset, and the Commercial Satellite Communications Office, or CSCO, can “just pull that information from the asset list, versus every vendor submitting it every time.”

By pre-qualifying the assets, IA-Pre will also mean an end to the lengthy cybersecurity assessments currently required during the procurement process itself, Reece said.

Critically, IA-Pre will also, for the first time, require third-party assessments. Currently, contractors self-attest that they meet required cybersecurity standards.

Under IA-Pre, asset owners will be required to hire qualified third-party assessors, who will review documentation that lays out the asset’s compliance with required control standards and baselines. “The third-party auditor is going to come in, review the system documentation against the baseline, and then submit their findings back to the government,” Reece said.

The assessors will be drawn from a pool of certified third-party assessors the Space Force maintains—known as Agents of the Security Control Assessor (ASCA)—who work to validate contractor compliance with existing security standards.

Such third-party assessments—involving time on site for hourly-paid consultants and their hotel and travel bills—can quickly get expensive, Reece acknowledged, adding CSCO was working with contractors to help them minimize such costs. “The strategy is to maximize the background off-site work and minimize the on-site work,” he said.

CSCO anticipated that the expense of compliance to IA-Pre would show up in increased pricing for the services it buys, Reece said. “We see that coming into the costs of the procurements that we’re doing,” he said.

The third-party process may come as a shock to some contractors, said Andrew D’Uva, president of Providence Access Company, a satellite technology consultancy.

“I won’t call anybody out,” D’Uva told CyberSatGov on Oct. 7. “But I’ll just say that the satellite community has, across the spectrum, taken varying approaches to self-attestation. One person’s version of ‘We met the requirement’ might not be the same as another person’s,” but they all counted for the same under self-attestation, he said.

IA-Pre would for the first time bring “transparency, and hopefully an objective set of criteria and practices that are being applied by … the IA-Pre assessors,” D’Uva said.

Reece said he expected some contractors to fail to meet the new standards. “I don’t anticipate 100 percent compliance upfront,” he said. But the 800-53 standard included a process for contractors to stay on the approved list while they work to achieve compliance. “If you don’t pass, you’re not going to get kicked off, you have chances to review and update that [evaluation],” he said.

The Plan of Action and Milestones (POAM) process produces a roadmap to repair any failings the IA-Pre evaluations identify, Reece said. “If they’ve got 30 controls where they’re non-compliant, they have to put a POAM out for each of those controls.”

The POAM process also allows contractors to explain why they can’t implement a particular control—and to offer alternative security measures and mitigations, Reece said, “The POAM can also say, ‘OK, because of the system, there are certain controls we can’t [implement] … we can’t do X, Y, or Z, here are our mitigations to this control.’”

The evaluations—POAMs and all—will be weighed by officials at CSCO and Space Systems Command, said Reece, but the objective was not to play ‘Gotcha,’ he said. “We don’t want industry to fail out and not be able to participate. We want to incentivize them, give them standards to achieve and push them to ensure that they’re selling us a secure solution,” he said.

IA-Pre aims to provide contractors a return on investment for their spending on security, said Reece. “We give them a chance to showcase their investment through these evaluations.” Compliance could be used as a factor in awarding contracts under a relatively recent procurement innovation known as Best Value Trade Off. BVTO replaced the old Lowest Price, Technically Acceptable standard that basically compelled acquisition officials to always buy the cheapest product.