A pair of Pentagon officials working on joint all-domain command and control say an effort is needed to address “a lack of synchronization” on the project across the services—and to potentially expand cooperation.

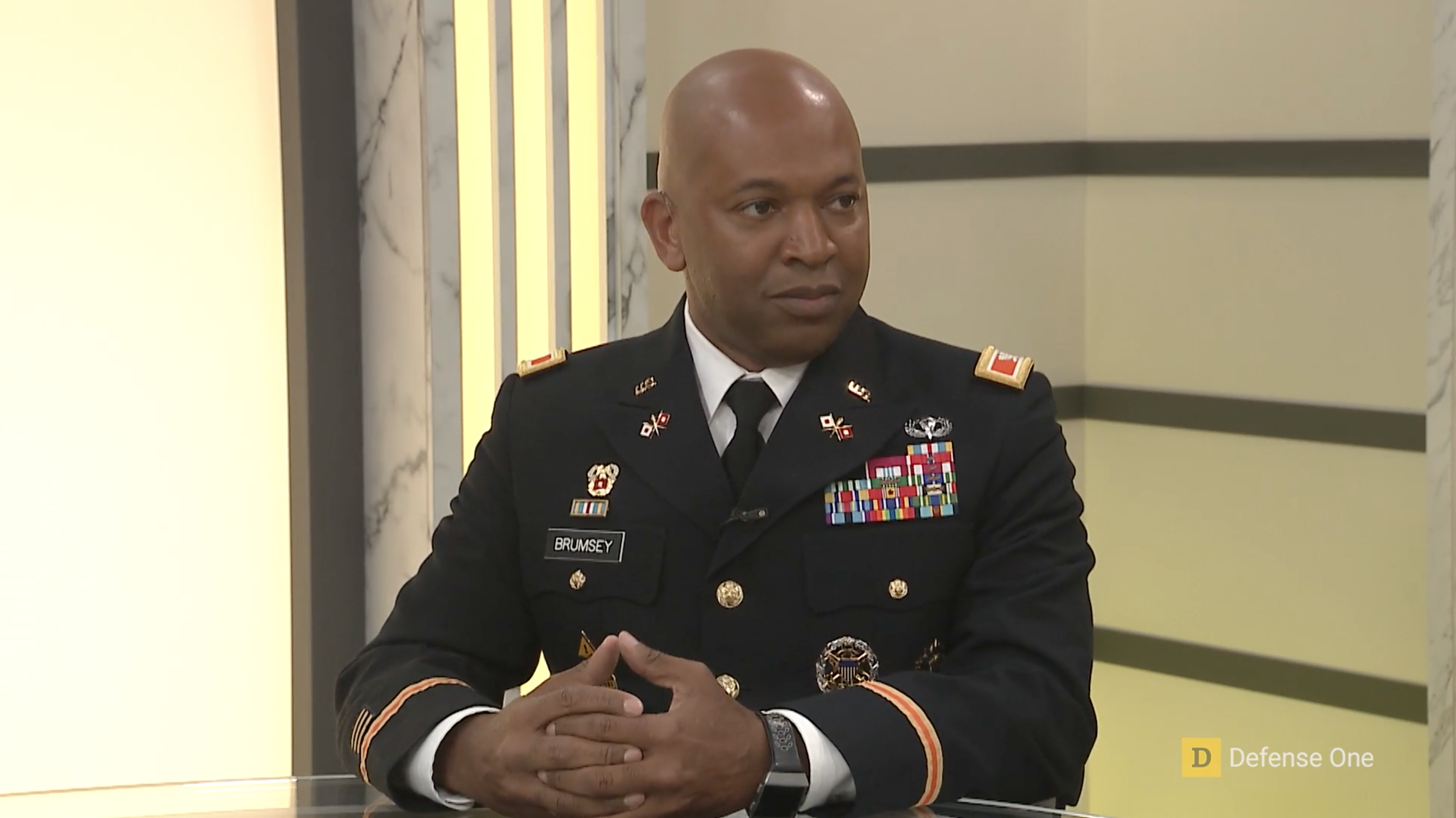

Speaking at Defense One’s Tech Summit on a panel called “JADC2 and the Future Warfighter” on Dec. 14, Army Col. Corey L. Brumsey, a member of the Joint Staff’s JADC2 cross-functional team, cited interoperability, or lack thereof, as one of the biggest challenges currently facing the team.

“For example, we have issues as far as the joint messaging format—so being able to send messages from the Navy to the Army and vice versa. We weren’t able to fully do that because of incompatibility with some of the software,” Brumsey said. “We know what to do. But we have to accelerate the process of how we can get it done quicker so we can have that full interoperability across the board.”

Brumsey witnessed the problem firsthand at Project Convergence 2021, an Army experiment in Yuma, Ariz., in October and November that sought to incorporate the other services’ JADC2 projects such as the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System. The results weren’t perfect, Brumsey said, but the effort was worthwhile.

“Some certain notes that were brought back from the exercise were saying, ‘OK, hey, we didn’t achieve all of the goals that we set to accomplish, but we’ve learned a lot, and so this is a learning campaign,” Brumsey said. “As we continue to move forward, looking at Project Convergence ‘22, we’re looking at bringing in some of the Five Eyes partners.”

Five Eyes is the intelligence-sharing alliance between the U.S., the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Incorporating allies and partners into JADC2 experiments has been pitched by the Army before, but there’s a push right now to define and tackle the problem through an effort dubbed the “Interoperability 2.0 Challenge” by Marine Corps Col. Noah Spataro, the chief of the Joint Assessment Division.

With “current C2 systems, developing C2 systems, the weapons and effects and capabilities that those things tie to, and the legacy components—whether they’re sensors or the C2 environments—[we’re] trying to really understand exactly what are all the different versions and message sets and cross-capability sharing that we need to be able to do,” Spataro said.

Brumsey and Spataro’s concerns about interoperability and JADC2 are not the first time the issue has been raised. In August, defense analyst Todd Harrison wrote in a brief for the Center for Strategic and International Studies arguing that the lack of coordination between the services on JADC2 was a “recipe for disaster,” with stovepiped approaches potentially never getting connected.

At the time, Harrison advocated for one service to take the lead in a joint program office to ensure the connectivity efforts were coordinated. He suggested that the Air Force or Space Force take charge, reasoning that many of the sensors necessary to make JADC2 work will be based in space and that communications will likely involve space as services turn to free-space laser communication, also called lasercom.

A policy paper from the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies published Dec. 15, “The Backbone of JADC2: Satellite Communications for Information Age Warfare,” largely echoed Harrison’s thoughts.

“Communications may not be sexy, but it is fundamentally the basis of JADC2, ABMS, Project Convergence. It is fundamental,” retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, dean of the Mitchell Institute, told reporters. “Without this kind of assured connectivity that’s going to be provided by our space-based architecture, it just will not happen, period.”

One of the major challenges to that interoperability, the policy paper contends, has been a lack of JADC2 coordination across services.

“Interoperability—I think this is sort of a DOD-wide problem. There’s a lot of different elements to this, and a lot of the different things—whether it’s ABMS, Project Convergence, Project Overmatch—they’re all looking at ways to get different systems to communicate better with one another,” said one of the paper’s authors, senior analyst Lukas Autenreid. “You need these systems to be able to interact effectively. But I think this issue is particularly bad in the [satellite communications] enterprise. You have a lot of systems that are highly integrated, but they’re incredibly stovepiped.”

To address that issue, Autenreid recommended that the Space Force take the lead in developing open standards and launching a constellation of hundreds of low-Earth orbit satellites to reduce latency in communications, increase coverage, and ensure resilience. The policy paper lists promising experiments within DOD to advance satellite communications in low Earth orbit, including the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency’s Blackjack program and the Transport Layer of the Space Development Agency’s plan for a National Defense Space Architecture.

Connect that network of satellites and ensure even better coverage and faster speeds, Autenreid said, with laser communications—such as those planned for SDA’s Transport Layer.

“Some of you may say, ‘Well, these communications have been around for a while, you know, what’s changed to make this so important now?’ And I think what we’ve been seeing is both in terms of the advancement in the technology itself, in terms of being able to miniaturize it,” Autenreid said, and dramatic improvements in the quality of laser optics.