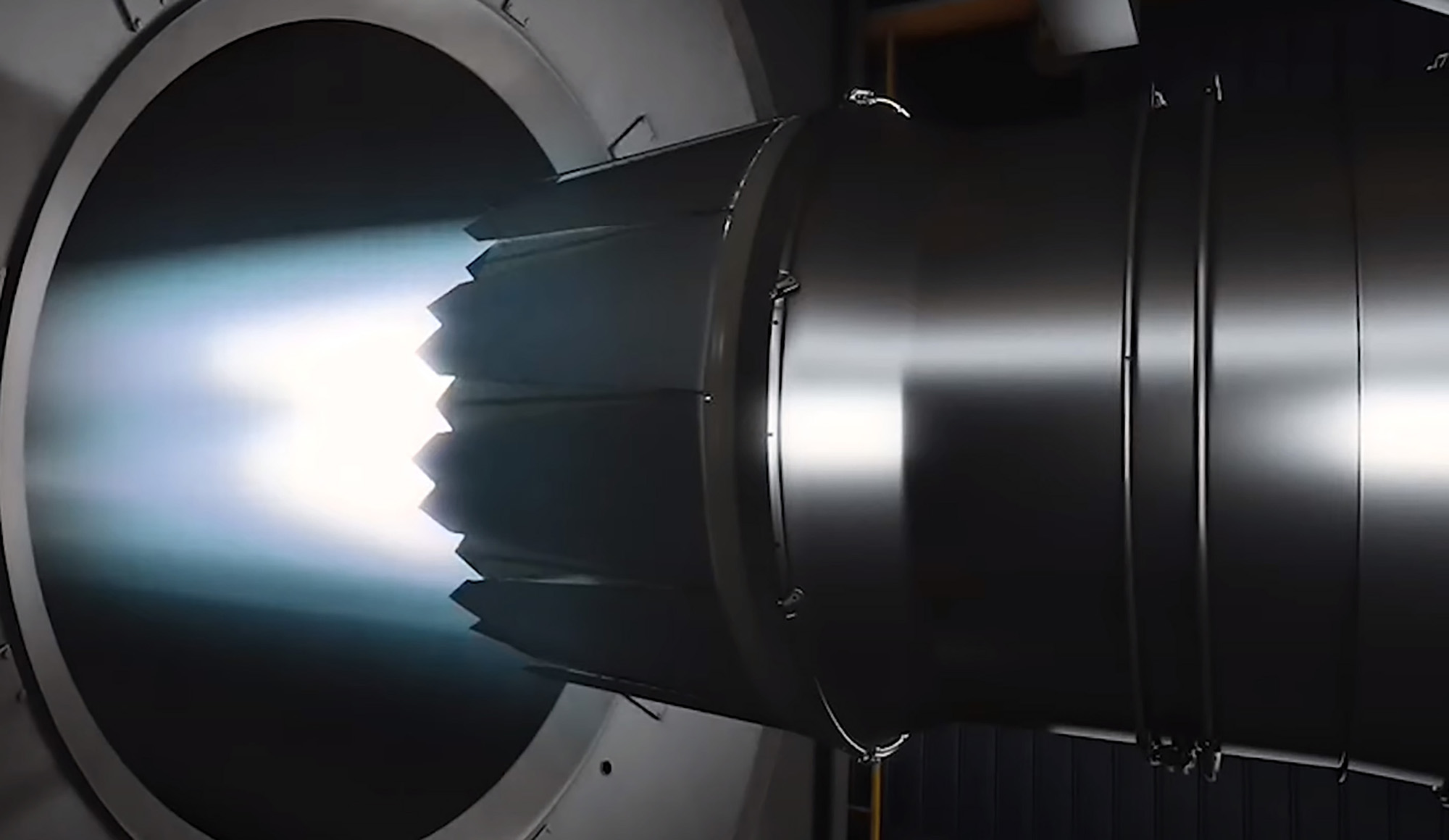

F-22s arrived at RAF Lakenheath, U.K., on July 26 en route to Poland, as the U.S. Air Force continues to bolster its presence of fifth-generation fighters in the region.

U.S. Air Forces in Europe confirmed the F-22s’ arrival, stating in a release that the fighters from the 90th Fighter Squadron of the 3rd Wing at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, will be traveling from Lakenheath to the 32nd Tactical Air Base in Lask, Poland, to support NATO’s air shielding mission.

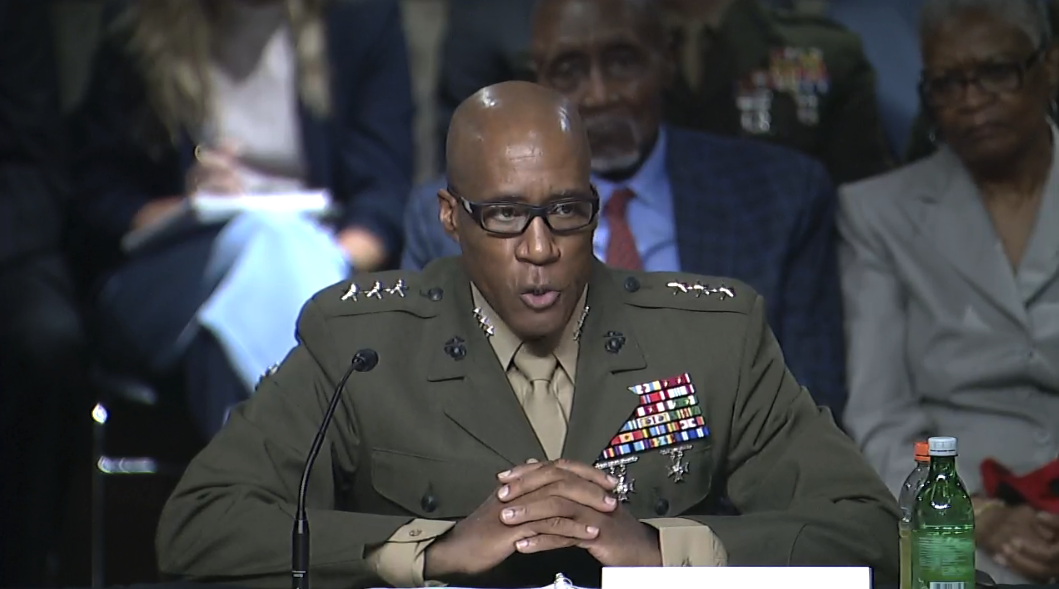

New USAFE commander Gen. James B. Hecker hinted at the F-22s’ appearance in Europe at the Royal International Air Tattoo on July 17 in an interview with Air Force Magazine.

“We’re bringing over F-22s … that are going to be coming over shortly, within a month, and they’ll spend four or five months over here,” Hecker said. “So we’re going to constantly cycle in fifth-generation in addition to what will eventually be two permanent [F-35] squadrons at Lakenheath. So we’ll be cycling it in here in the meantime.”

According to local media reports, six F-22s arrived at Lakenheath. When they arrive in Poland, they’ll be tasked with supporting a new mission for NATO. Air shielding is intended to protect NATO nations from air and missile threats by leveraging air- and ground-based air defense assets.

Air shielding “will provide a near seamless shield from the Baltic to Black Seas, ensuring NATO Allies are better able to safeguard and protect Alliance territory, populations and forces from air and missile threat,” USAFE’s press release states, adding that the F-22’s success as an air dominance platform makes it “a highly strategic platform to support NATO Air Shielding.”

This marks just the latest deployment of USAF fighters to eastern Europe in an effort to reassure NATO allies on the eastern flank in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and continued aggression.

Earlier in July, F-35s from the Vermont Air National Guard forward-deployed to Amari Air Base, Estonia, to support the air shielding mission. Prior to that, the Air Force has moved F-15s, F-16s, other F-35s, and still more aircraft into Eastern Europe, participating in NATO’s Baltic air policing and enhanced air policing missions.

The constant rotation of new aircraft into the region is part of the Air Force’s plan to remain vigilant as the Russia-Ukraine war drags on.

“What we’re going to do is just kind of have six, 12 kinds of airplanes that will come in here for four months, and we’ll do that for about a year or so, in addition with all the permanent aircraft that we have stationed here,” Hecker told Air Force Magazine. “And that will increase our presence here, and then we’ll have to readjust and see what this thing looks like a year from now, and then we can adjust as necessary.”