Outgoing commander of U.S. Africa Command Gen. Stephen J. Townsend said Moscow has used its mercenary Wagner Group to install air defenses in Mali, a troubled West African country that has seen a marked increase in terrorist activity under a new military government.

Ruled by a military junta following a May coup, Mali first kicked out French counterterrorism troops then withdrew from a regional security group, instead increasing its cooperation with the Russian proxy Wagner Group.

“Wagner is a Russian mercenary group working at the behest of the Kremlin,” Townsend told journalists on a July 26 media call from AFRICOM headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany.

Townsend said that while Russia’s war in Ukraine has pulled some Wagner Group resources out of Libya, Russia has increased its proxy presence in Mali.

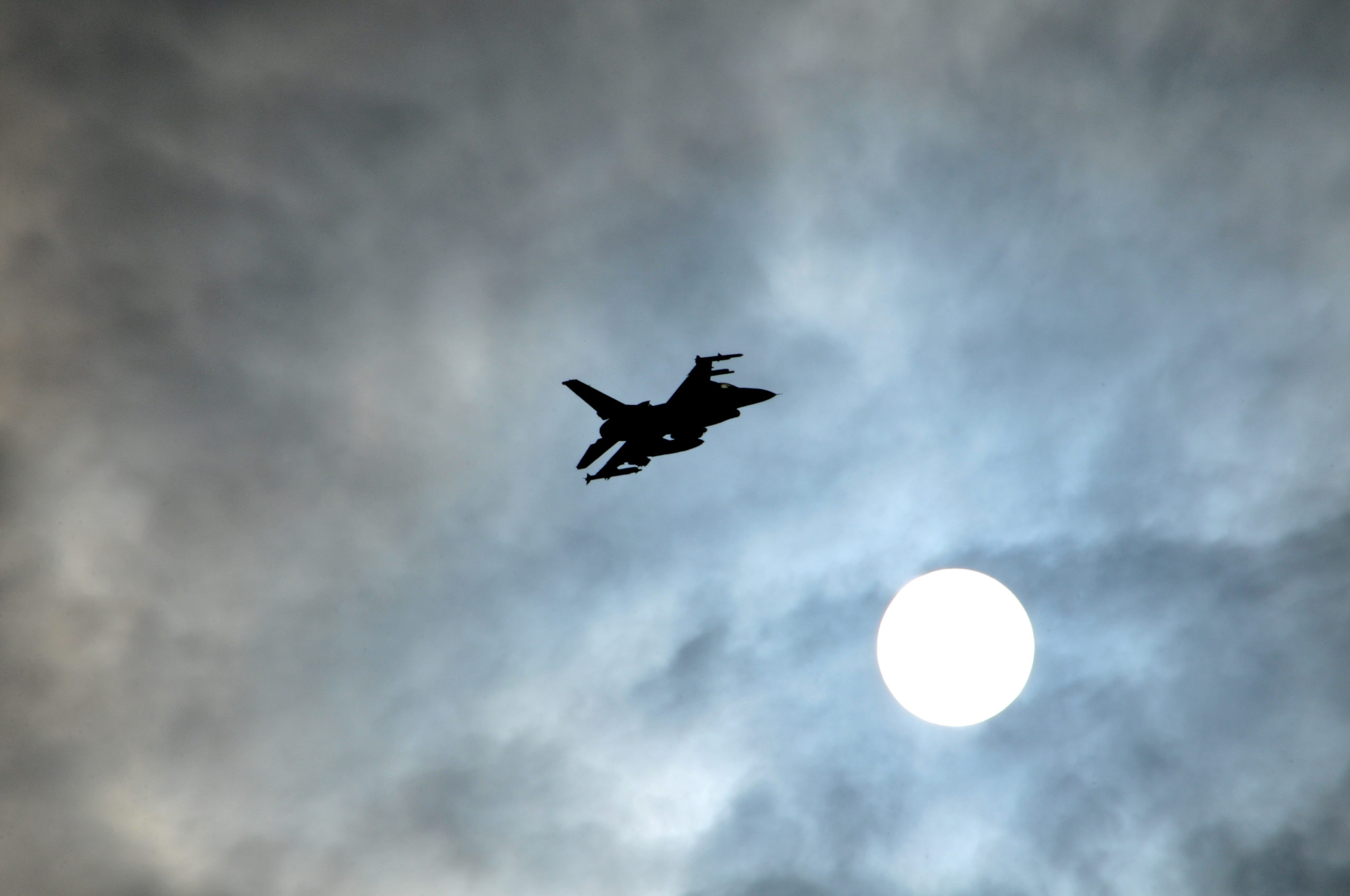

“So far, they do not appear to be drawing down in Mali,” Townsend said. “In fact, they appear to be leaning in to Mali as much as they have been throughout. In fact, they’ve deployed sophisticated new capabilities like air defense capabilities to Mali that we have seen appear there recently.”

U.S. Africa Command and U.S. Air Forces in Europe-Air Forces Africa did not immediately respond to questions from Air Force Magazine about the new threat the air defenses pose to U.S. Air Force operations in the Sahel region.

Townsend said Russia has expanded its influence in Africa through the proxy group, which has contributed to instability and political uncertainty.

“Though the Kremlin likes to deny it publicly, they are an arm of the Kremlin, and they are doing President Putin’s bidding,” Townsend said. “The only thing I see Wagner doing is propping up dictators and exploiting natural resources on the continent.”

Russia was previously estimated to have 2,000 Wagner Group fighters in eastern Libya supporting Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army, which has fought against the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord, which is recognized as Libya’s official government by the United States and the United Nations. In 2020, AFRICOM released images of some of the 14 MiG 29s and Su-24s Russia sent to support its Wagner forces in the Libyan desert.

In recent months, Russia has pulled back some of its proxy manpower to fight in Libya, but Townsend said 1,000 remain deployed to Mali, plus a “substantial” number are in the Central African Republic and elsewhere on the continent.

“They’ve gotten a footprint in a number of other countries, but those are probably some of the big ones,” Townsend said.

Townsend acknowledged that the military takeover in Mali and cooperation with Russian forces is hindering Western attempts to contain terrorism in the arid region of West Africa known as the Sahel, where the United States maintains two MQ-9 bases, Air Base 101, and Air Base 201, in neighboring Niger.

“What we see is we see these threats expanding,” Townsend said, describing ISIS-West Africa as the dominant terrorist force in the region.

“In Mali, and Burkina Faso, al-Qaida’s arm JNIM have been on the march towards the south” and the capital of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, he added. “They’re starting operations now in the northern border regions of the coastal state. So, this is a great concern.”

Townsend spoke to journalists as part of a series of media appearances in the final weeks of his tenure as AFRICOM commander. July 26 marked his third anniversary as leader of the Africa-focused combatant command.

In comments to Air Force Magazine in Fairford, U.K., the new commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe-Air Forces Africa Gen. James B. Hecker said MQ-9 Reapers in Africa are operating around the clock.

“If required, we can arm those ISR platforms as well to provide a kinetic activity, if we need that. So that’s a big part of our job in Africa,” he said, nothing that some platforms remain airborne for 24 hours at a time to gather intelligence for AFRICOM.

In the past, AFRICOM has shared that intelligence with French forces operating in Mali and the regional G-5 Sahel Joint Force group, which was made up of forces from Niger, Mauritania, Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mali.

But Mali kicked out French forces and withdrew from the G-5 on May 15.

All spell new challenges for both Hecker and Townsend’s successor, Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Michael E. Langley, who is expected to take over AFRICOM in a change-of-command ceremony at Kelley Barracks in Stuttgart on Aug. 9, pending congressional approval for a fourth star and confirmation as new AFRICOM commander. The Senate Armed Services Committee advanced Langley’s nomination July 26.

“In light of the continued expansion of terrorists, irregular changes of government in the region, arrival of malign groups like the Russian mercenary group, Wagner, and recalibration by other partners such as France, and others, the United States is also recalibrating our approach,” Townsend said. “We’re striving to find a way to become more effective in the future.”