Facing a moment with no historical precedent, the United States needs to recalibrate to deal with two nuclear peers in China and Russia—and to modernize its entire nuclear enterprise, a top general with U.S. Strategic Command warned Feb. 7.

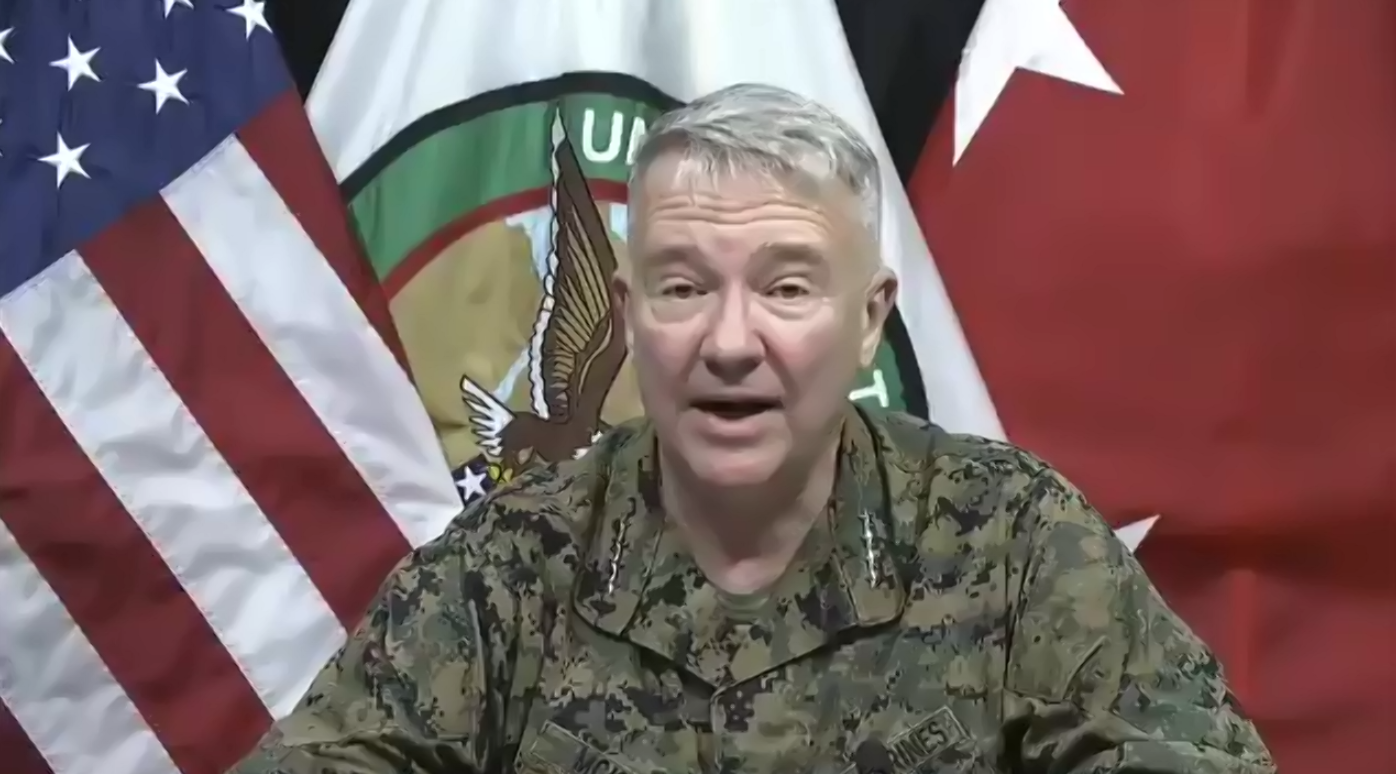

Air Force Maj. Gen. Ferdinand B. Stoss, STRATCOM director of plans and policy, issued his warning while appearing virtually at the 2022 Nuclear Deterrence Summit. Speaking to an audience of industry officials, academics, and others, Stoss painted a picture of a strategic environment that, in some ways, goes beyond even what the U.S. faced during the Cold War.

“I think we can agree that the United States, our allies, our partners—we have not faced this type of threat in over 30 years,” he said. “And not just a threat, though. Like I mentioned before, this is the first time ever that we have a three-party nuclear peer dynamic. And we have no history of this. This is epic. And I don’t think we’ve fully dealt with all the ramifications that this is going to have as we march into the future, but we absolutely need to.”

For decades now, Stoss added, the U.S. has been engaged in conflicts in which it could mostly control the level of violence. Now, however, that’s changed.

“Today, both Russia and China have the capability to unilaterally escalate at any level of violence, across any domain, into any geographic location, … and to do so at a time of their choosing,” Stoss said.

Of the two, Russia is the greater shorter-term threat, Stoss said, as it develops “novel weapons” with awesome destructive capability but questionable safety.

The Russians are building “everything from their … hypersonic anti-ship vehicles to their Skyfall nuclear-powered intercontinental-range cruise missiles,” Stoss said. “I’ve heard others opine, they call it a ‘flying Chernobyl.’ And it’s not far from the truth, what with their safety, or lack thereof, with that capability.”

China, meanwhile, is building up its own capabilities in a manner that Stoss called “breathtaking,” echoing the words of his boss, commander of U.S. Strategic Command Adm. Charles “Chas” A. Richard.

Throughout the summer and fall of 2021, satellite images revealed that the Chinese were building hundreds of missile silos, and the Pentagon’s own report on Chinese military power estimated that China could possess 1,000 nuclear weapons by 2030, a number Stoss repeated.

“’Why are they doing this strategic breakout?’ Well, we don’t exactly know. They are very opaque as to what they are doing with nuclear, and they always have been,” Stoss said. “But, you know, perhaps this is just one more brick to put into the wall to cement their capacity to play a much bolder role, certainly in the region and around the world, and they think that they need this nuclear underpinning.”

What’s important to remember, Stoss added, is that this kind of growth doesn’t happen by accident or without heavy planning and investment.

“To be sure, to have this type of a breakout and the capabilities they’re bringing online would have taken them years to plan, to develop, and then to actually build,” Stoss said.

The Pentagon, on the other hand, is in the midst of trying to develop a host of new programs, including the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, the Long-range Standoff Weapon, the B-21 bomber, the Columbia-class submarine, and a new nuclear command, control and communications (NC3) network.

The need to modernize so many different capabilities at the same time, Stoss said, is something the U.S. brought on itself.

“One common thread that I think we have across the department: The three legs of the triad, our NC3, and our nuclear weapons complex is, we took a knee on these systems,” Stoss said. “And, unfortunately, now that we’ve taken that knee and we’ve accepted these risks, we’ve found that … we no longer have the option to take that risk, that we’re doing just-in-time modernization, really across the board. That may not be applicable to each and every system, but it certainly is when you look at the whole.”