Aug. 30 marks the one-year anniversary of the end of Operation Allies Refuge (OAR), the final act in the longest war in U.S. history. Historians will long study the United States’ post-9/11 Global War on Terrorism and, in particular, the failed, two-decade effort to plant sustainable seeds of democracy in Afghanistan. Certainly as a coda to the conflict, OAR reflected the chaos, tragedy, and good-intentions-gone-awry that characterized so much of the Afghan War.

What was accomplished a year ago under the most challenging of conditions and pressures was largely overshadowed by a horrific suicide bombing that killed more than 170 people at Hamid Karzai International Airport, including 13 U.S. service members; an errant U.S. drone strike that killed 10 Afghan civilians, including seven children; and by the dispiriting spectacle of flag-waving Taliban extremists sweeping to victory in Afghanistan 20 years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

On this one-year anniversary, however, the fog of war that enshrouded so much of Operation Allies Refuge has largely lifted. Revealed beneath the chaos and tragedy is the largest non-combatant evacuation operation (NEO) airlift in U.S. history, one that involved round-the-clock operations of nearly 800 military and civilian aircraft from more than 30 nations. In just 17 days, more than 500 U.S. Air Force Active, Reserve, and National Guard aircrews and hundreds of Air Force ground personnel helped evacuate a staggering 124,334 people, the vast majority of them Afghan nationals.

Heroism and great compassion were behind those unprecedented numbers. Airmen helped deliver three babies aboard C-17s during the operation, and dozens more were born shortly after their mothers landed safely at staging bases and temporary safe havens around the world. Air Force Aeromedical Evacuation teams and medics stood up “Operation Stork,” gathering the specialized personnel and equipment required to safely transport the roughly 20 percent of adult female evacuees who were pregnant. U.S. Air Forces in Europe and the 521st Air Mobility Operations Wing created passenger medical augmentation teams to attend to the needs of evacuees who were in many cases wounded and traumatized, and crammed shoulder-to-shoulder in flights of more than 450 passengers per sortie. Their efforts included multiple life-saving resuscitations inflight.

After the suicide bombing at HKIA, three Aeromedical Evacuation missions whisked 35 patients to care, saving the lives of the critically wounded. In all, 28 Aeromedical Evacuation missions conducted during OAR flew 177 patients to badly needed care. One of the C-17s from the 21st Airlift Squadron also carried the 13 fallen U.S. service members killed in the bombing home to Dover Air Force Base, Del.

For the one-year anniversary of Operation Allies Refuge, Air Force Magazine interviewed a number of the many Air Force participants, the better to remember their largely untold stories of bravery and compassion in the face of deadly chaos.

‘Not the Afghanistan We Knew’

Just days after the United States military had officially furled the flag on Operation Resolute Support in Afghanistan, Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III issued a vocal order on July 16, 2021, instructing the U.S. Air Force to deploy a personnel recovery task force (PRTF) to Hamid Karzai International Airport. The PRTF’s mission was to provide combat search and rescue in support of a U.S. non-combatant evacuation operation (NEO) for tens of thousands of Afghans who had served as interpreters, drivers, and assistants to U.S. forces and diplomats.

The Pentagon avoided such a move for many months, concerned that a mass exodus would demoralize Afghan allies. The plan at the time was still to leave behind a large U.S. diplomatic presence in Kabul to support the Afghan government and security forces. In July, however, Taliban insurgents intensified an offensive that had already seen them capture more than a third of provincial capitals around the country. A new U.S. intelligence assessment that took note of those negative trends warned that the Afghan government could fall within the next six to 12 months, as opposed to the two- or three-year window that the intelligence community assessed only months earlier. That Afghan institutions might collapse in just weeks had not yet occurred to U.S. intelligence analysts.

The day after Austin’s deployment order, the State Department announced Operation Allies Refuge, and the Air Force was directed to organize relocation flights for Afghan nationals and their families eligible for U.S. Special Immigrant Visas. In the classified briefing at the operations center for the 71st Rescue Squadron at Moody Air Force Base, Ga., the wing commander explained to the deploying Airmen that “the hair on the back of your necks should be standing up: This is not the Afghanistan we knew.”

Lt. Col. Brian Desautels was chosen to command the personnel recovery task force, which included combat search and rescue (CSAR) units and helicopters from Moody as well as Nellis and Davis-Monthan Air Force Bases. Along with many senior officers, Desautels had spent much of his career fighting America’s longest war, but in 20 years of operations in Afghanistan, U.S. Air Force units had become accustomed to operating out of large, secure military bases with abundant ground support such as Bagram and Kandahar airfields. At Hamid Karzai International Airport (HKIA) in Kabul, the task force would operate out of a facility wedged into the middle of a sprawling capital of nearly 5 million people, with no hardened base support or dedicated security force. The task force would thus need to carry all the food, water, equipment, and expertise it would require in the coming weeks.

The deployment amounted to an unprecedented stress test of the Air Force’s agile combat employment (ACE) concept, with pressures few could imagine at the time.

“I had served in Afghanistan, so I knew what my commander was talking about in terms of the hair standing up on the back of our necks, but we are used to operating out of austere airfields and making the best of it,” Desautels said in an interview. He noted that the roughly 170 multi-mission-capable Airmen of the task force were wheels up in three C-17 “chalks” in less than 72 hours, arriving at HKIA within 96 hours of receiving the deployment order. By mid-August the PRTF had settled into a good battle rhythm, helping to evacuate on average 7,500 civilians each day. “We hit the ground running with a lot of focused energy, committed to giving 100 percent until our mission was complete.”

Then one morning in mid-August, Desautels entered the operations center at HKIA to find that Rear Adm. Peter Vasely, a Navy SEAL and the top U.S. commander in Kabul, was wearing his full “battle rattle” and carrying his M-4 rifle. There was also a new sense of urgency in the orders he barked. Taliban forces were sweeping into Kabul, and the U.S. Embassy had yet to be fully evacuated. As Desautels entered the operations center, an Army captain saluted and requested permission to abandon his post because they were taking so much sniper fire from nearby rooftops. He was given reinforcements from the PRTF team instead.

Desautels worked 27 hours straight and was grabbing a couple of hours sleep when he awoke to the sound of explosions and heavy machine-gun and automatic weapons fire. Jumping out of his rack, he grabbed two bug-eyed majors and headed for the operations center. There was screaming and multiple conversations talking over each other on the radio net. With the Taliban entering the capital virtually unopposed, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country and Afghan Security Forces had melted away.

“Then the Taliban opened fire on the airport, and suddenly word came that the whole airfield was being overrun by thousands of desperate Afghan civilians,” recalled Desautels. “The whole perimeter was collapsing around us.”

‘I Couldn’t Help But Think of My Own Daughter’

After U.S. forces abandoned Bagram Airfield in July, chief medical officer and Air Force Col. Bruce Lynch and roughly 50 members of his staff relocated to the U.S. Embassy in Kabul. As the top medical adviser for Adm. Vasely, he felt acutely the tension between a U.S. military command anxious to evacuate the embassy and a U.S. ambassador and embassy staff determined to keep the faith with their allies in the Afghan government.

“At the embassy. it was in the back of everyone’s mind that things weren’t going well for the Afghan government, and by early August when two or three major provincial capitals fell to the Taliban, you could read the tea leaves, but we didn’t want to abandon our Afghan partners and exacerbate their problems by making a hasty exit,” Lynch said in an interview. Working alongside an Afghan doctor he had met at Bagram, Lynch helped treat Afghan soldiers who were wounded defending Kabul, and the two physicians became close.

When Kabul fell to the Taliban on Aug. 15, the embassy staff were finally hustled into helicopters and transported to HKIA. Given the incredible stress of the moment, Lynch was relieved to be greeted at the airport not by surly Turkish soldiers who were previously in charge, but rather by young U.S. Marines in full battle gear.

“On such a hectic day, it was quite a relief to get off the helicopter and be greeted by a bunch of U.S. Marines on the runway. That was calming to me,” said Lynch, who along with his team was ushered to the medical facility at HKIA that would serve both as their workplace and home for the next two weeks. Luckily the medical center was fairly new, with a well-equipped and modern emergency room, two operating rooms and an intensive care unit. Most important, the HKIA medical center was a hardened facility of brick and concrete with no exterior windows. Given the proximity of high-rise buildings surrounding the airport, it was a relief for the medical team not to feel they had a constant target on their backs.

In one of the conversations with the Afghan physician he had worked with at Bagram and the embassy, Lynch learned that the man had a 12-year-old daughter who was nearly the same age as Lynch’s own children.

“We were exchanging stories about our kids, and he told me that his daughter wanted to be a doctor like her father when she grew up,” recalled Lynch, who knew that a whole generation of young Afghan women and girls who had grown up with unprecedented freedoms in a fledgling democracy would soon be subjected to the medieval patriarchy of the Taliban. “In the back of my mind, I remember thinking that the options for his daughter’s future would be pretty grim under Taliban rule, and as a father, I couldn’t help but think of my own daughter in such a situation. It was a horrible thought.”

Later Lynch learned that neither the Afghan doctor nor his daughter were able to escape during the evacuation.

‘Rightly Concerned’

When the emergency call came in mid-August, Col. Colin McClaskey was on a mission in the Horn of Africa. As deputy commander of the Air Force’s 821st Contingency Response Group out of Travis Air Force Base, Calif., he led a unit that specialized in opening, operating, and, if necessary, closing airfields. His team included air traffic controllers, aircraft maintenance personnel, military police, fuel specialists, and logisticians. And the word came that the situation in Kabul was essentially going to hell, and they were needed there yesterday.

With the rest of his team already underway from the United States, McClaskey took a C-130 transport from Djibouti, Africa, to Ramstein Air Force Base, Germany. There he hitched a ride on a C-17 transport that was ferrying U.S. Army troops to Kabul, part of an emergency deployment of some 6,000 U.S. Soldiers and Marines being rushed to HKIA to try to secure the airport. After refueling in Kuwait, the C-17 approached the Kabul airport Aug. 15. Sitting in the cockpit in the right observer seat as the aircraft circled low over HKIA, McClaskey could hardly process what he was seeing. The airport looked like a crowded soccer stadium during a riot, with thousands upon thousands of people outside trying to cram through the various gates and thousands more running onto the tarmac and taxiways like they were a football pitch.

“I was talking to the aircrew and over the radio with members of my team already on the ground at HKIA as we flew low over the airfield,” said McClaskey. “I don’t know that there was anybody in that airspace that wanted to be on the ground with their team more than me at that moment. But as we talked through the situation very frankly, we all agreed that putting the aircraft down would risk both it and those people on the ground. In the end, we had to divert back to Al Udeid, and I can tell you [as we left], my folks on the ground were rightly very concerned about their physical security.”

‘We’re Staying’

“Everyone just calm the f*** down! We’re launching the iron, but we’re not flushing the whole team! We’re staying,” Lt. Col. Desautels shouted into the radio in the operations center, referring to the two HC-130 aircraft that were designated to fly his team to safety in the event of an emergency exfiltration. With the perimeter breached and thousands of Afghan civilians swarming the tarmac, the situation at HKIA was deteriorating by the second, and many people in the operation center and around the world via television footage were unnerved by what they were witnessing.

A C-17 Globemaster that had just landed at the airport to deliver a load of equipment and security forces were swarmed by hundreds of Afghan civilians before it could even offload its cargo. Faced with possibility of losing control of their aircraft and jeopardizing all those onboard, the pilots quickly taxied and took off, with Afghan civilians clinging desperately to the fuselage and wheel wells. The sight of Afghans falling as the C-17 gained altitude would become an iconic image of OAR, recalling photos of U.S. helicopters pulling desperate Americans and South Vietnamese off the roof of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon in 1975.

Just minutes later, Desautels had to make a life-or-death decision. In the event that HKIA was completely overrun not only by Afghan civilians but potentially Taliban fighters, he had promised his team he would get them out or “flush” them on the two HC-130 aircraft designated “Fever 11” and “Fever 12.” Now that the moment had apparently arrived, Desautels also understood that pulling his 170-person team, many providing airport security, would leave a critical gap in the airport’s already crumbling defenses.

“We had intelligence that the Taliban had liberated a nearby prison full of al-Qaida and ISIS fighters, so my team understood how critical we were to the base defense plan. So instead of flushing the team, I got permission from the CFACC [Combined Forces Air Component Commander] to launch the HC-130s from the taxiways, which is risky. Word came back that ‘the airport is not clear, take off at your own risk,’ and within seconds Fever 11 and 12 were airborne flying just 30 feet or so above the heads of the crowd on the runway.”

With the aid of air refueling tankers, the increasingly exhausted pilots of the HC-130s circled overhead for more than 13 hours, waiting to see if the U.S. military could regain control of the airfield. The alternative was to attempt an emergency extraction of the personnel recovery task force from a contested airfield.

‘A Gut Punch to Everyone’

Late in the afternoon Aug. 26, Lynch stepped out of the medical facility at HKIA for a breath of fresh air. The scene that greeted him outside was almost post-Apocalyptic. The shells of abandoned cars were scattered about, and piles of discarded suitcases, bags, mattresses, and the other detritus of lives torn asunder littered the area. A stench escaped from a nearby line of latrines that had not been emptied in days.

Due to intelligence indicating a possible suicide bombing attack on the airport, leadership had put the small hospital on lockdown for much of the day. Most of the doctors and nurses were sleeping at the facility after their shifts anyway, so they really had no place else to go. Then around 6 p.m., word came that there had been a suicide bombing across the airport at Abbey Gate, which U.S. Marines guarded against a swirling mass of as many as 10,000 Afghan civilians desperately hoping to be rescued. The mass of humanity provided an inviting target for the Islamic State-Khorasan terrorist who had packed his suicide vest with ball bearings for maximum lethality.

Lynch immediately activated the mass casualty plan his team had rehearsed many times. Yet no amount of planning could prepare them for the arrival of the first trucks carrying the wounded.

“When the first truck pulled up and we saw all of the Marines injured in the back, that was a game changer. That was a big shock to me personally and a gut punch to everyone. I don’t think any of us had seen so many American casualties from a single incident, and it was clear that four or five of the Marines had passed away already,” said Lynch. “But after stepping back for a moment, we had to jump-start ourselves out of the shock because so many wounded were coming in, and we had to be on our ‘A game’ to take care of all the patients.”

Enlisting the help of a group of Air Force pararescuemen, Lynch quickly established a triage point outside the facility. He walked up and down the lines of wounded, deciding who needed to be rushed into the emergency room, which patients had less severe wounds that could be treated elsewhere in the hospital, and who lacked a pulse and was beyond help.

During one of the longest nights of his life, Lynch realized that the small hospital was in danger of being overwhelmed, doubling up in the emergency room and treating 63 U.S. and Afghan wounded in the small facility. The staff had already confirmed 10 American fatalities, some having died on the operating table. In their mass casualty plan, they had anticipated having to treat patients without dog tags or easy identification, so they created packets for them and gave each one the name of a Hollywood celebrity. They quickly ran out of celebrity names and had to think of others.

By early morning, the last of the Aeromedical Evacuation flights transporting the wounded to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany lifted off. An exhausted Lynch looked around a hospital very much the worse for wear. He knew the team would have to find the energy to clean up and reset the facility in case the airfield was attacked again. After all, they were still in the middle of Kabul; the base was still surrounded by the Taliban; and other Islamic State-Khorasan terrorists were undoubtedly still out there plotting massacres.

Soon, medical corpsmen started showing up with blood donations, and Marines arrived to help clean the hospital, mopping floors, taking out the trash, and disposing of bloody bandages and sheets. That allowed Lynch and his team to get a little rest, but not much. Lynch knew that every day until their scheduled departure Aug. 31 would be more dangerous than the previous one.

‘An Opportunity to Actually Deliver Hope’

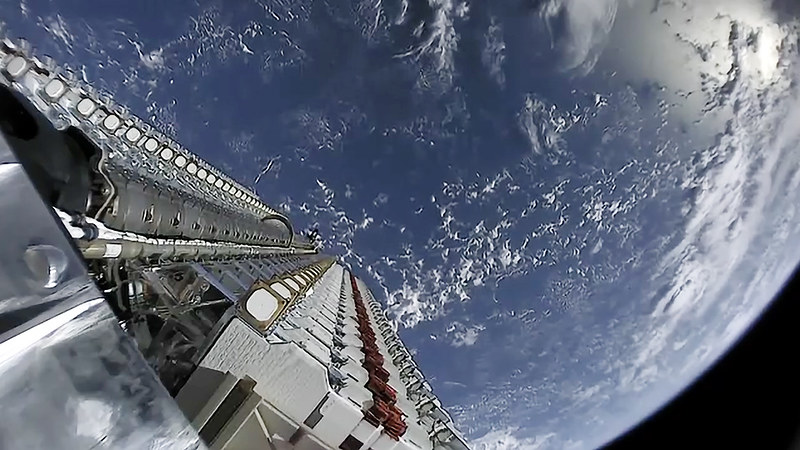

After flying four evacuation missions out of HKIA in a matter of days, C-17 pilot Lt. Col. Austin Street was on his first extended crew rest at Al Udied Air Base in Qatar. The ramp of the air base had been expanded to accommodate more than twice the number of C-17s as normal, one of many signs that the Globemaster had become the workhorse of Operation Allies Refuge. Roughly half of the Air Force’s entire fleet of 222 C-17s had been committed to the operation, and they would evacuate more than 79,000 of the more than 124,000 total evacuees, including roughly 6,000 Americans.

Street, commander of the 21st Airlift Squadron out of Travis Air Base, Calif., was asleep when the phone call came from the operations desk at Al Udied. There had been a mass casualty suicide bombing at HKIA, and he was designated to command an Aeromedical Evacuation mission to transport the wounded to Germany. But when Street arrived at the aircraft for the high priority mission, only one maintenance person was on site prepping the aircraft. He also learned that because the heat in Qatar had the effect of expanding jet fuel, he would have to launch without a sufficient fuel load to complete the mission. To make matters worse, some of the generators at HKIA had been targeted by saboteurs, meaning he would have to land at night without runway lights.

The Aeromedical Evacuation flight was so rushed that the two aeromedical transport teams and critical care air transport team onboard had to reconfigure the aircraft to accept wounded patients while underway to Kabul. No midair refueling tankers were in range. Once on the ground at HKIA, Street had to wait two hours on the tarmac with the aircraft engines running because some of the critically wounded passengers were just out of surgery and needed to be stabilized before transport.

Once again, Street took off without enough fuel to complete the mission and reach Ramstein Air Base in Germany. Initially air command-and-control could identify no tankers in range, but they finally located a KC-135 tanker on “strip alert” in the region. Street conducted a tricky midair refueling at night over the Black Sea, while in his cargo bay a critical care team performed emergency surgery on a wounded patient.

“I’ve flown the C-17 for 15 years, and that was not only the most important and significant mission I ever flew, it was also the most challenging,” Street said in an interview. At Air Mobility Command, he noted, their mission mantra is to ‘project power, and deliver hope.’ “Well, I’ve had lots of opportunities to project combat power into war zones, but I’ve rarely had the opportunity to deliver hope. That’s why I’m so proud of my crew for pushing through and overcoming the most challenging conditions I ever witnessed. This entire operation was an opportunity to actually deliver hope, not only to our own wounded, but also to all the Afghans trying to get out of Kabul. That allowed the American military to keep faith with many of those Afghans that we’ve built trust with over the past 20 years.”

‘An Eerie Feeling’

On the final day of Operation Allies Refuge, McClaskey led a skeleton crew from the 821st Contingency Response Group as they launched the final evacuation flights from HKIA. The suicide bombing days earlier had given his team a renewed sense of purpose, and they had worked around the clock to get as many Afghans out of the country as possible in what little time remained. Even in the last 24 hours of operations, they had managed to rescue 1,250 additional evacuees.

McClaskey and his team finally policed up the last remnants of equipment at HKIA, determined to leave nothing of combat usefulness for the Taliban fighters they could see all around the airport’s perimeter, their signature black-and-white flags unfurled. Everything that couldn’t fit into the rear of a C-17 was destroyed.

That evening under the cover of darkness, five C-17s would help the 82nd Airborne Division execute a joint tactical exfiltration, flying the remaining 800 U.S. personnel at HKIA, including the acting U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, to safety. The C-17s were supported by more than 20 orbiting aircraft stacked overhead, to include command-and-control, strike, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms.

When the ramp closed on his C-17 on Aug. 30, 2021, McClaskey knew his long Afghan War was over.

“At that point, I thought about the first time I flew into Afghanistan right after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and how many subsequent birthdays I had spent flying to this country. I also thought about the thousands and thousands of Americans injured and killed there, some of whom I had flown out of there, and the countless lives and families changed as a result of this war,” said McClaskey. “It was an eerie feeling, and a lot to unpack. I’d spent my entire career fighting in these conflicts, and now it was all over. At that moment, I couldn’t wait to call my wife and tell her we were on our way home.”

James C. Kitfield is a contributing national security correspondent and author, and a three-time recipient of the Gerald R. Ford Award for Distinguished Reporting on National Defense.