The Air Force has awarded a pair of contracts to Boeing potentially worth more than $3.1 billion combined for 19 KC-46s—four for Israel—the Pentagon announced Aug. 31.

The larger of the two deals is worth roughly $2.2 billion and will go toward the KC-46’s Production Lot 8, made up of 15 of the aerial refuelers, the contract award states. Work will take place in Boeing’s Seattle facility and is expected to be completed by Nov. 30, 2025.

While those jets will go to the U.S. Air Force, the other contract calls for four tankers to be delivered to Israel. The cost cannot exceed $927 million.

That cost also covers “the non-recurring engineering design and test for the Remote Vision System 2.0 and the Air Refueling Operator Station 2.0 mission equipment and installation, pre-delivery integrated logistics support, and technical publications,” the contract award states.

Work will also take place in Seattle and is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2026.

Israel’s interest in the KC-46 dates back years. The State Department approved the sale of up to eight of the tankers to Israel in March 2020, and in late 2021, the Israeli Defense Ministry signed a deal.

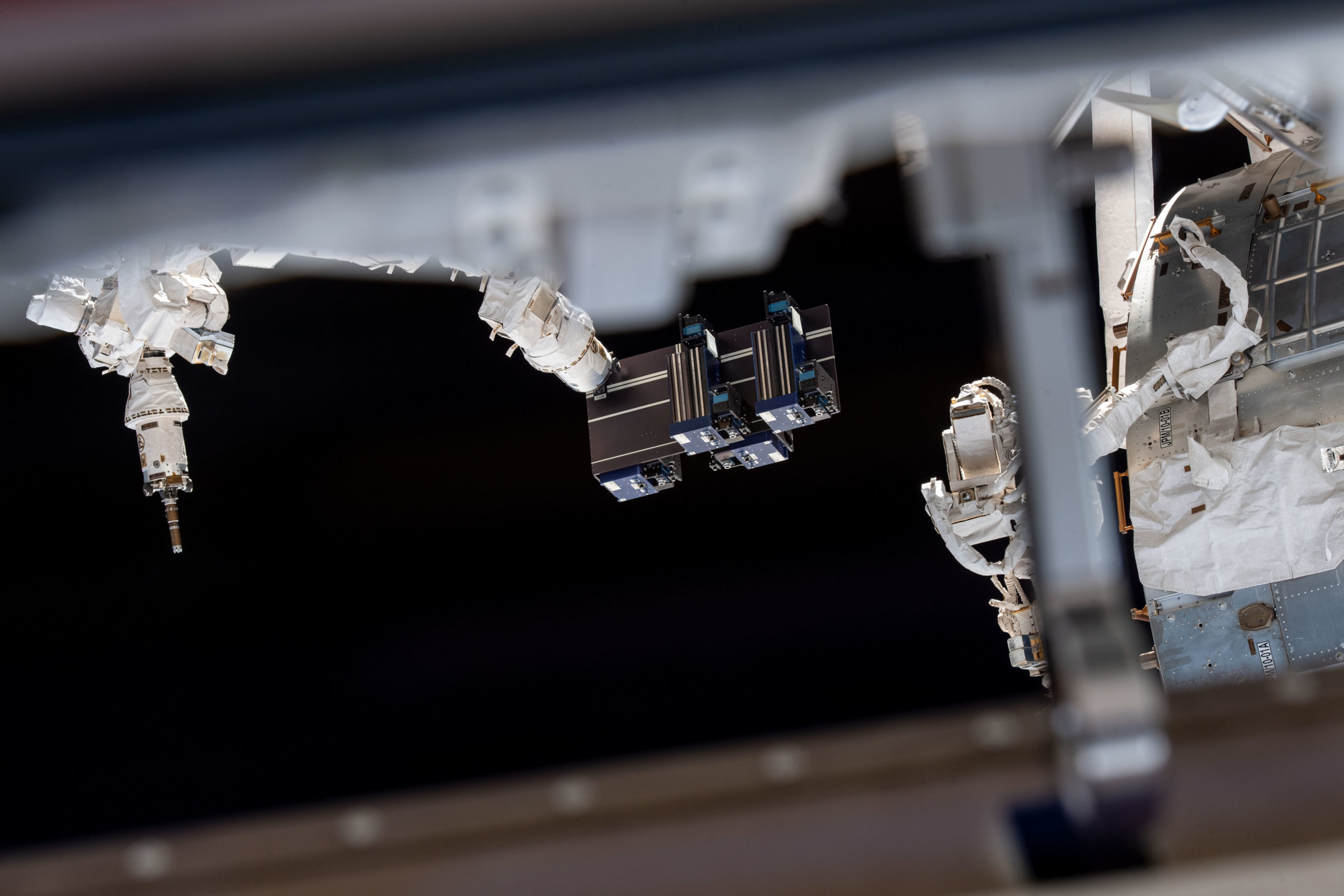

For the USAF, the latest lot of KC-46s will come as the service continues to work with Boeing for a solution to the troubled Remote Vision System. Blackouts and washouts on the tanker’s video displays, caused by shadows or direct sunlight, have raised the possibility of the boom scraping a receiving aircraft and have prevented the KC-46 from being cleared for combat operations.

The Air Force and Boeing have been working on a replacement, dubbed RVS 2.0, for several years now. The final design was approved in April 2022, with Boeing agreeing to pay for upgrades, but installation isn’t scheduled to begin until 2024.

The contract for Lot 8 comes nearly 20 months after the award for Lot 7 in January 2021. That production lot, also comprising 15 aircraft, cost $2.12 billion.