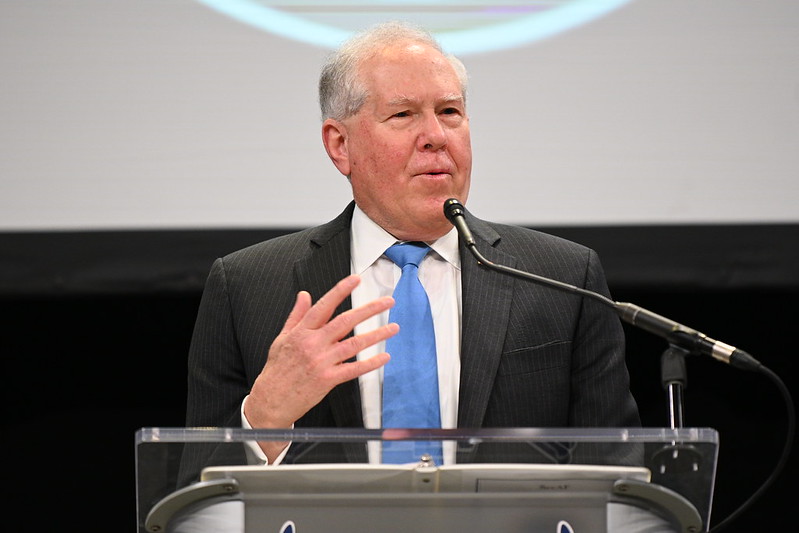

The Defense Department needs to upgrade its IT, add more software specialists, and empower certain programs to be more innovative—especially when it comes to artificial intelligence, the former CEO of Google said March 3.

Eric Schmidt, who led Google and its parent company Alphabet from 2001 to 2015 and chaired the Defense Innovation Advisory Board, delivered a keynote address at the AFA Warfare Symposium in Orlando, Fla., offering what he called several “blunt” criticisms and recommendations for the Pentagon.

“In the tradition of the military, I will be direct and I hope that’s OK,” Schmidt told an audience of Airmen, Guardians, and industry leaders. “If I look at the totality of what you’re doing, you’re doing a very good job of making things that you currently have better, over and over and over again. But I’m an innovator. And I would criticize, if I could say right up front, that the current structure, which is an interlock between the White House, the Congress, the Secretary of Defense’s [office], the various military contractors, the various services, and so forth, is a bureaucracy in and of its own. And it’s doing a good job at what it has been asked to do, but it hasn’t been asked to do some new things.”

Schmidt did note one exception to that criticism—the B-21 Raider program. Praising the Rapid Capabilities Office, Schmidt said the Air Force developed the new stealth bomber in a “new and innovative” way.

The challenge now is to take that approach and apply it to programs across the DOD, Schmidt said, especially to non-hardware platforms.

“Every time you try to do something in software, one of these strange scavenging groups within the administration takes your money away. It’s insane,” Schmidt said. “The core issue here in the military is you don’t have enough software people. And by software people, I mean people who think the way I do. You come out of a different background, and you just don’t have enough of these people.

“These are hard people to manage. They’re often very obnoxious—sorry, welcome to my field. They’re difficult. They’re sort of full of things, but they can change the world, and a small team can increase your productivity of whatever you’re doing.”

This issue is particularly glaring when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), Schmidt said. And not only does the military lack the necessary personnel, the defense industrial base does too. Touring the symposium’s exhibition hall, Schmidt said he only saw “like two AI companies, … and by the way, they’re the little ones in the corner.”

Just like the B-21 program has been innovative, there are some examples of good software development, Schmidt said, pointing to Project Maven, a DOD AI project that ignited controversy among Google employees, but which Schmidt said has had “very successful classified use in the right ways.”

But Project Maven was just one project, and “to be very blunt, you don’t have enough people, you don’t have the right contractors, and you don’t have the right strategy to fill in this,” Schmidt said of the Pentagon’s work in AI. “We need 20, 30, 40 such groups—more, more, more. And as that transformation happens, the people who work for you, the incredibly courageous people, will have so much more powerful tools.”

Schmidt’s intense enthusiasm for artificial intelligence is born out of his belief that “AI is a force multiplier like you’ve never seen before,” he said. “It sees patterns that no human can see. And all interesting future military decisions will have as part of that an AI assistant.”

Schmidt is hardly alone in predicting AI will have a seismic impact on warfare. But advocates say they’ve also encountered resistance and inertia within the Pentagon.

Such doubts are preventing the U.S. military from fully embracing AI’s possibilities and forcing service members to “spend all day looking at screens doing something that a computer should do.”

Potential uses include precision weapons targeting, precision analysis, and autonomous systems, Schmidt said. But to get there, there’s something the Pentagon has to do first.

“The real problem you have is that you don’t have enough bandwidth, … which no one ever tells you this,” Schmidt said. “Your networks, excuse the term, suck. You’ve got to get the networks upgraded. You just have to, because all of these things depend on that kind of connectivity, right?”

Schmidt’s comments were met with applause from his audience—the issue of poor network connectivity and IT systems is a constant source of frustration among Airmen and Guardians.

Yet despite all this, perhaps the biggest issue facing the Air Force’s software and AI efforts isn’t really about software.

“We love to talk about strategy, and we need more money over here, and by the way we do, and we need more partnerships over here, and yes we do, and we need more of this over here, and every state has to have its money and all of that’s fine,” Schmidt said. “But what we don’t have and we need a lot more of is the kind of talent to drive this world.”

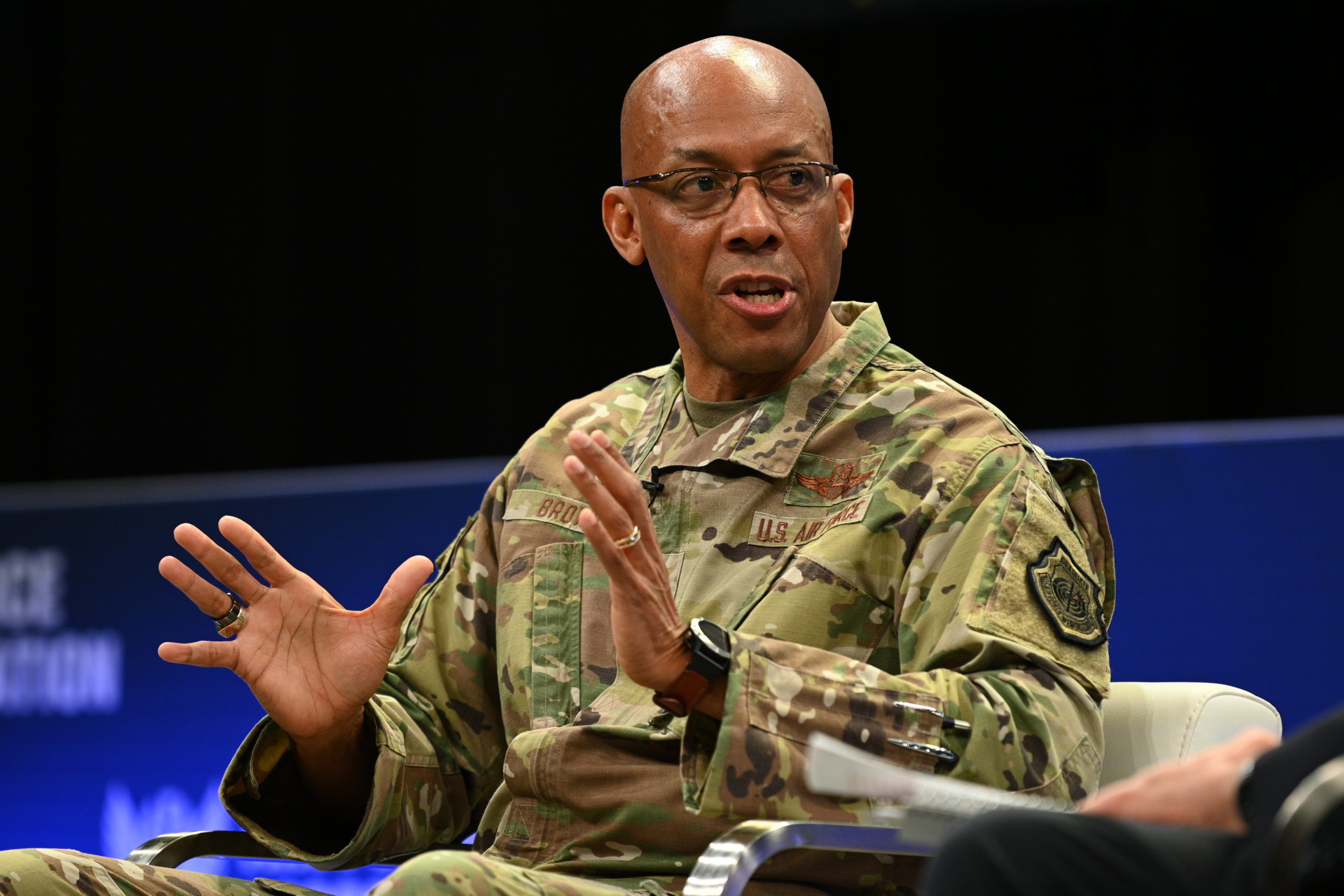

To attract and retain talent, Schmidt said, the military needs to empower innovators instead of holding them back, granting them a certain level of autonomy to make decisions and take risks. In that regard, his comments echo ones made by Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., who has made empowering Airmen one of the key themes and goals of his tenure.