The House of Representatives passed its version of the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act on July 14. The annual policy bill includes a $37 billion increase to the top line of the Pentagon’s budget and a number of provisions that will affect the Air Force and Space Force.

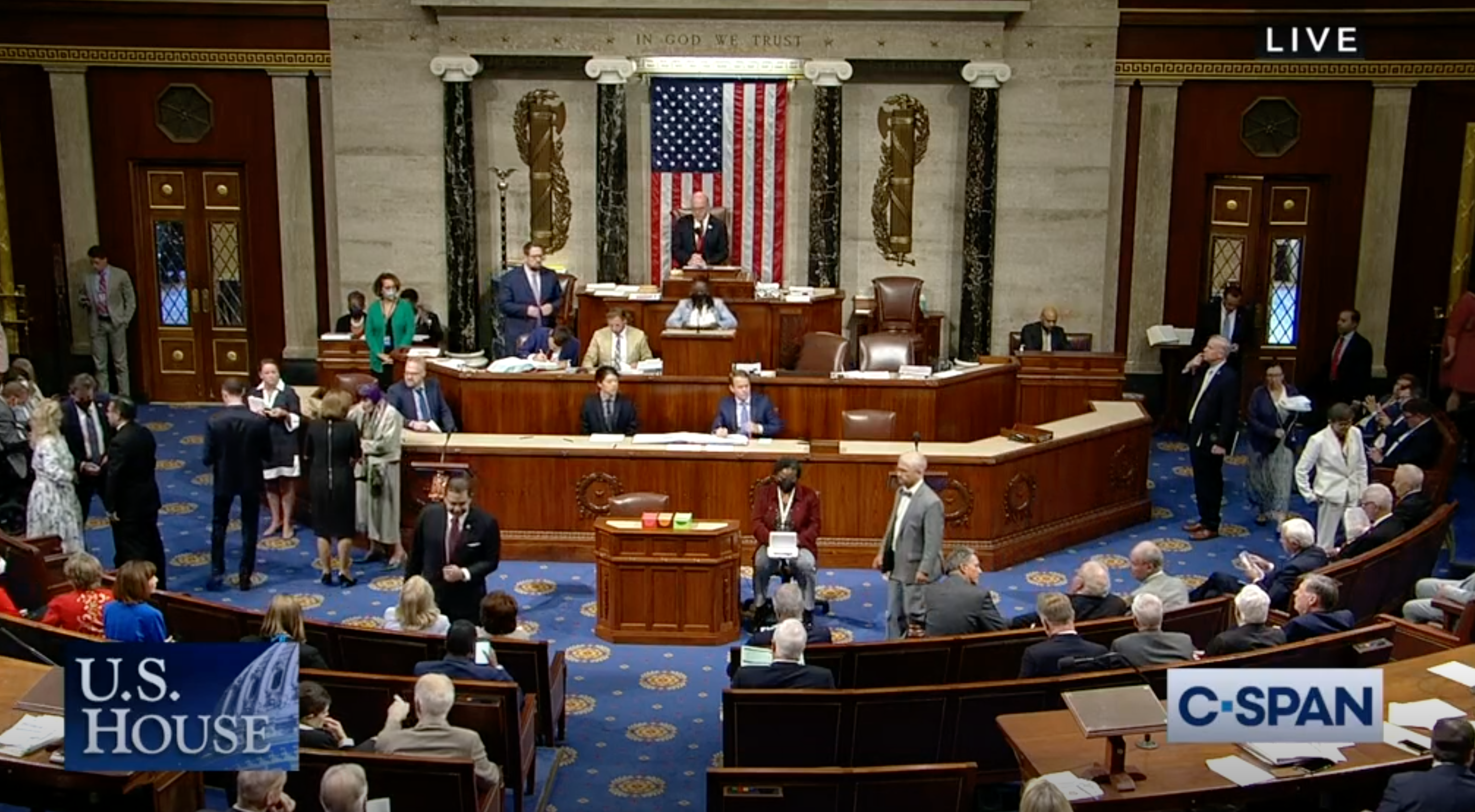

The final bipartisan 329-101 vote capped two days of deliberation on the House floor as lawmakers debated and voted on more than 600 amendments.

While NDAAs set policy and authorize funds, they do not appropriate the money the Defense Department spends. Still, they give Congress oversight of the Pentagon and are regularly considered “must-pass” legislation.

“For over six decades, the NDAA has served the American people as a legislative foundation for national security policymaking rooted in our democratic values,” Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), chair of the House Armed Services Committee, said in a statement. “Today’s successful vote marks another chapter in that history—with considerable gains for those currently serving our country in uniform.”

Among the amendments approved as part of the deliberation process was a provision from Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) to authorize $100 million to provide training to Ukrainian pilots and ground crews to become familiarized with American aircraft. Ukrainian pilots and defense officials have pleaded for the U.S. to provide them with aircraft such as the F-16, and while thus far the Biden administration has rejected those calls, Kinzinger’s amendment was agreed to in an uncontroversial voice vote.

Other amendments adopted by voice vote include one from Rep. Cliff Bentz (R-Ore.) that would limit the number of F-15s the Air Force can divest, at least until the service provides a report to Congress on the number of F-15s—including F-15Cs, Ds, Es, and EXs—it plans to buy and retire in the next five years, broken down by year and location, as well as an assessment of the negative impacts of such retirements and plans to replace those missions.

Kinzinger also introduced another amendment that was eventually approved as part of a larger package that prohibits the Air National Guard from retiring the RC-26 Condor, a tactical ISR platform, despite the fact that ANG leaders say it costs millions of dollars to maintain and other, cheaper technologies such as drones can perform the same missions.

But not all amendments were approved. Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), a senior member on the House Armed Services Committee, introduced one that would have suspended funding for the LGM-35 Sentinel, the Air Force’s modernization program for its intercontinental ballistic missiles, and instead extend the aging Minuteman III to 2040. That amendment was soundly defeated by a 118-309 vote.

Earlier in the legislative process, the House Armed Services Committee also voted against forcing the Air Force to hold a competition for its so-called “bridge tanker.” One thing the House NDAA would do, however, is force the Air Force to upgrade, not retire, its oldest F-22 fighters, despite the service’s request to divest them.

The NDAA also includes a provision from Rep. Jason Crow (D-Colo.) that would establish a separate Space National Guard, a move that was also approved by the House last year before being left out of the compromise version of the bill crafted with the Senate. This year, however, a bipartisan group of a dozen Senators have already proposed legislation supporting a Space Guard.

Finally, the House NDAA partially addresses the Air Force’s unfunded priorities list by adding $978.5 million to procure four more EC-37B Compass Call electronic warfare aircraft plus nearly $379 million for weapons system sustainment—shy of the $579 million included in the UPL.

The bill does not, however, add any more F-35As for the Air Force, leaving the service’s much-reduced purchase of 33 fighters unsupplemented.

With the NDAA through the House, the Senate must now pass its version of the bill before legislators from the two chambers can craft a compromise bill in conference to vote on and send to President Joe Biden.

“I am glad to see the FY23 NDAA pass the House with overwhelming bipartisan support. However, our work is not done—we will continue to improve upon this bill in conference to ensure that this legislation gives our warfighters what they need,” said Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.), the House Armed Services Committee’s top Republican.

Last year, that process lasted longer than expected. The House passed its version of the bill on Sept. 23, but the Senate struggled to do the same, to the point where leaders from both chambers finally unveiled a compromise bill on Dec. 7, bypassing the usual conference process. That bill cleared both chambers by Dec. 15 and was signed into law shortly thereafter.