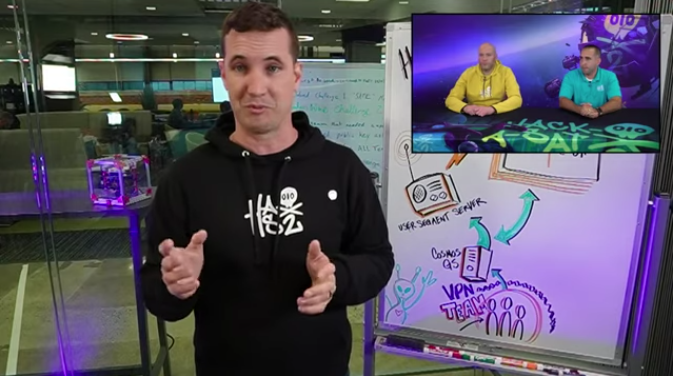

The Space Force’s second-ever Hack-a-Sat competition challenged hackers to find vulnerabilities in earthbound satellite hardware, drawing eight hacker teams to vie for tens of thousands of dollars in cash.

But while last year’s inaugural competition proved inspirational, this year’s ended amid complaints by participants, who said rules changing on the fly and poor communication by the organizers undermined the event.

Even those who performed well were frustrated. “We had really high hopes … for the contest, but at the end the disappointment and frustration completely took over, even after finishing second and winning a big cash prize,” wrote Michał Kowalczyk on CTFTime, a blog where contestants rate and review different capture-the-flag (CTF) competitions. Kowalczyk, whose hacker handle is Redford, is a co-founder the team “Poland Can Into Space,” which was the runner-up both this year and last. “I wish it was different, but I have to say that this was a pretty bad CTF.”

Organizers said they are working on the issues and trying to communicate directly with participants to ensure problems this year can be addressed ahead of future competitions.

CTFs have grown since the 1990s into an international hacker subculture, with hundreds of contests every year. The competitions build teamwork and develop a collaborative muscle memory while at the same time helping security researchers hone and practice defensive and offensive skills.

The Space Force said the contest is “designed to inspire the world’s top cybersecurity talent to develop the skills necessary to help reduce vulnerabilities and build more secure space systems.”

Hack-A-Sat 2 was organized by representatives from the Air Force Research Laboratory, the Space Force’s Space Systems Command, and Cromulence, a contractor. Organizers said they will address the criticisms in follow-up meetings with the eight teams.

“We appreciate feedback and just as we did last year, we plan to have individual feedback sessions with each team to learn what worked well and what can be improved on for next year,” organizers wrote in a statement to Air Force Magazine.

Disappointment and Frustration

In an “attack-defend” CTF such as Hack-A-Sat, teams of “white-hat” hackers compete over an intense and often sleepless 24 to 48 hours. Each team must both defend its own satellite replica while attacking the replica systems defended by the other competitors.

“Hackers tend to be very direct people, very open about their opinion,” said Rubin Gonzalez, a founder of FluxRepeatRocket, a team based in Germany and the fourth-place finisher this year. “So if something went wrong they will generally have no problem with publicly stating that something was wrong.”

Gonzalez said his team wasn’t invited to the Slack channel used to communicate with competitors until well after the final round began, an oversight that left the team blind. “So for the first three hours, we had no idea what was going on,” he said. “We weren’t getting any of the information or announcements.”

Tyler Nighswander of Plaid Parliament of Pwning, a storied team connected with Carnegie Mellon University, complained that “lots of things regarding how the game operated were not explained clearly.”

Joshua Christman of Pwn-First Search described “a lack of communication and a lack of transparency.”

Poor communication made it hard for competitors to understand scoring awards and other decisions that, left unexplained, appeared arbitrary.

“Part of the problem is that organizers were and are ignoring our questions,” Kowalczyk said. “So we don’t really know the explanations and details for some of the things which happened.”

The organizers, in their statement, defended their communication style, noting that answering competitors’ questions had to be done in a way that didn’t unfairly influence the competition.

“Due to the nature of an attack/defend CTF, where teams are progressing at their own individual pace through the challenges, we have to address all [teams’ questions] in a manner that doesn’t disclose the solutions [to] the other teams because this would provide unfair advantage to the inquiring teams. If one team has figured something out, then it’s unfair to them to provide any hints or additional information to other teams,” the statement explained.

The organizers said that—as they did last year—they would publish an archive of all the Slack messages during the game.

Some participants defended the organizers. “No CTF is without its flaws/mistakes, but these organizers have always run good competitions in the past,” said Jonathan Elchison, one of the founders of SingleEventUpset, a team put together especially for Hack-A-Sat.

Atypical Challenge

All CTFs are technically challenging to stage, noted Elchison, but running one on hardware systems such as satellites, with embedded software and very different architecture from the conventional IT systems that most CTFs stage their competitions on, is “particularly difficult.”

Organizers used eight centrally located flat sats—real satellite hardware, but earthbound—as the systems that each team had to attack and defend. But they also provided teams with a digital twin of the satellites, a software emulation of the hardware systems on the flat sats.

“The contest goals were very ambitious,” agreed Nighswander, noting that “with such a complicated game to create, there was certainly a higher amount of technical effort than usual needed.”

“In a typical CTF,” explained the Hack-A-sat organizers, the different parts of the competition, known as “challenges,” tend to be independent from one another. But satellites—even the ground-based simulators or “flat sats” used in the contest—are “systems of systems” in which functions, also called services, depend on each other.

“For HAS2, the challenges were interrelated and sometimes dependent on each other due to the nature of the flight software running on the flat sat hardware,” the organizers said. “This architecture drove many of the decisions made about scoring and the rules of engagement for the competition.”

Most criticism centered on these two elements. Gonzalez and other competitors said rules of engagement changed mid-game; and that the scoring system lacked the accustomed transparency—teams couldn’t tell why they were gaining or losing points.

A dashboard representing the flat sats’ systems and subsystems showed a system in green if it was functioning normally or in red if it wasn’t. Teams thought red meant they were losing points, but the organizers announced during the course of the game that if a system turned red, “that does not necessarily mean that you are losing points for it, it is simply a basic visualization.”

The organizers said they had to strike “a delicate balance in releasing just enough information about the scoring so that teams cannot game the system.” In a contest centered on hacking satellites, their statement continued, “the expectation was that teams knew what services on the satellite are critical.”

Nonetheless, they promised to do better next year. “With that said, we could improve our dashboard in the future to be more representative of the SLA metrics that were a factor in scoring.” Most of the points contestants could earn came from a service-level agreement, or SLA—they got points for keeping the various systems on their satellite functioning at a certain minimum level.

High Expectations

In the end, said Nighswander, the contest reached the right result: “I think the first and second placed teams Solar Wine and Poland Can Into Space were the ‘correct’ teams. They both did a great job, and they deserved their places, and I think that is very important.”

He suggested that expectations for Hack-A-Sat were high. “I think all of the participating teams have played in CTFs which were run worse than this contest was,” he said. But given that Hack-A-Sat was backed by the resources of the U.S. military, competitors expected a flawless execution. “There was an expectation level that I don’t think was cleared,” he said.

Gonzalez said the contest this year took “a step in the wrong direction,” but he hoped the organizers would listen to the criticisms because it’s “a really cool event.”

Solar Wine, the multinational Francophone team that won the contest and the $50,000 first prize, declined to comment on the controversy. “We will communicate our feedback to [the organizers] privately, as we did last year when we missed the podium for a technicality,” said team member Aris Adamantiadis.

He hoped the controversy wouldn’t overshadow their victory. He noted that, as well as a personal achievement for Solar Wine team members, the result also represented something of a breakthrough. “The big American CTFs are usually led by American teams,” he said, noting that Hack-A-Sat 1, although won by a U.S. team, had Polish and German teams in second and third places.

Solar Wine has members from France, Belgium, and Mauritius, Adamantiadis said, but the diversity that helped them win was their “diversity of skills. We have people specialized in the security aspects of reverse engineering, exploit development, cryptography, networks, IT infrastructure, scripting languages, and now even space packets, astrophysics, and satellite operation. All of these skills were key to navigate through Hack-A-Sat,” he said.

Winning, Adamantiadis concluded, was “an achievement that we are very proud of on a personal level of course, but there’s a bit of nationalistic pride, too!”