Nearly 50 members of Congress have urged Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III to fund a new phase of development for advanced fighter engines in the fiscal 2024 budget, sending a letter to the Pentagon on Oct. 7.

The letter, signed by 49 lawmakers from both the House and Senate, specifically requests that the Defense Department “fund adaptive propulsion engineering and manufacturing development in the FY24 budget submission and deliver adaptive technology to the services as quickly as possible.”

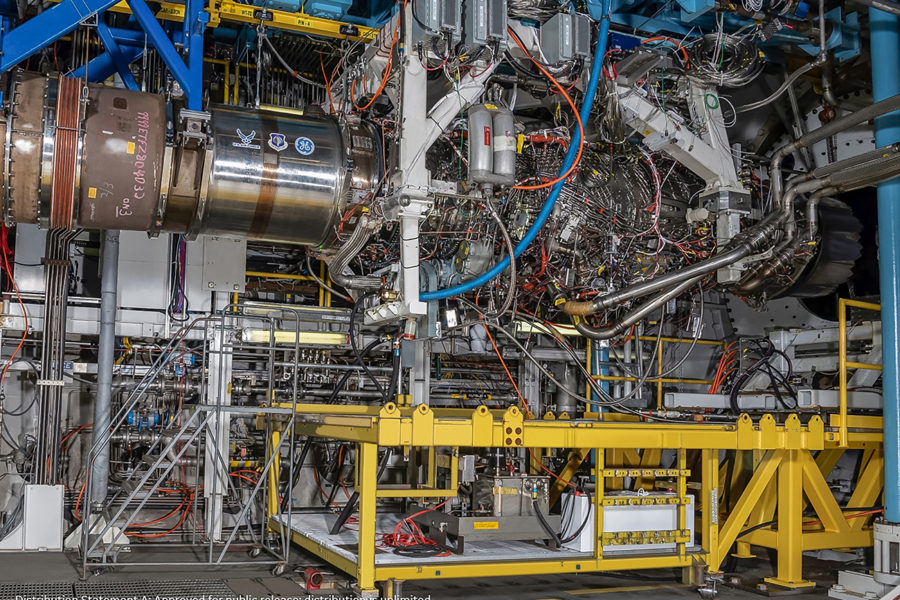

The Air Force has taken the lead in researching and testing adaptive engines through its Adaptive Engine Transition Program. Enginemakers GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney have developed three-stream prototypes that companies and USAF officials say could produce generational advances in propulsion. With the ability to maximize for thrust in combat situations and fuel efficiency in cruising conditions, such engines could increase range, acceleration, and thermal management.

The future of the program and the prototypes that came from it, however, are in doubt, tied to the controversy over the future of F-35 propulsion.

GE Aerospace has pitched its engine, the XA100, as a replacement for the F-35’s current engine, the F135, which has suffered from sustainment issues.

Pratt & Whitney, on the other hand, has pushed instead for an incremental “Enhanced Engine Package” upgrade to the F135, saying that the adaptive engines should be introduced with the service’s Next Generation Air Dominance fighter.

While some officials have touted the capabilities of the adaptive engines for the F-35, other observers have argued that the cost of installing them could be prohibitive, especially given that they will not fit on F-35Bs and the F-35 program is structured so that customers have to “pay to be different,” meaning the Air Force would not be able to share costs.

Congress, for its part, included language in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act calling for AETP engines to be installed in F-35As starting in 2027, a move that would put pressure on the Air Force to shift AETP from a research, development, test, and evaluation phase into an engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) one.

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has seemingly indicated that the service will make a decision on an EMD phase—or ending the program completely—in the near future. On two occasions in recent months, he predicted a decision in the 2024 budget, at one point saying he doesn’t want to “limp along,” continuing to spend money on research and development for AETP.

“The Department of Defense has to make a decision overall about engine modifications and upgrades for the F-35. I expect that process to take place over the next few months as we build the [fiscal 2024] budget,” Kendall told lawmakers in May. “What the Air Force has funded is continuing the AETP technology development, but we’re going to need to have a decision at a higher level about the overall program for F-35 engine modifications and upgrades.”

That continuing technology development is seemingly nearing its end. In September, GE Aerospace announced that the XA100 had completed its final testing milestone as part of AETP, with the company saying in a press release that it was “ready to transition to an Engineering and Manufacturing Development program.”

In the letter to Austin, the bipartisan group of lawmakers don’t tip their hand in favor of either GE’s XA100 or Pratt & Whitney’s XA101. Instead, they ask that DOD include factors such as “capability and the cost of failure” in its budget analysis, hinting that monetary cost shouldn’t be the determining factor in a choice.

The lawmakers also link the future development of adaptive engines to the Defense Department’s top priority of competing with and deterring China.

“To support the administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, we must continue to develop and field advanced propulsion systems which will enable our service members to fly into the theater of operation, complete their mission and return home safely,” the lawmakers wrote.

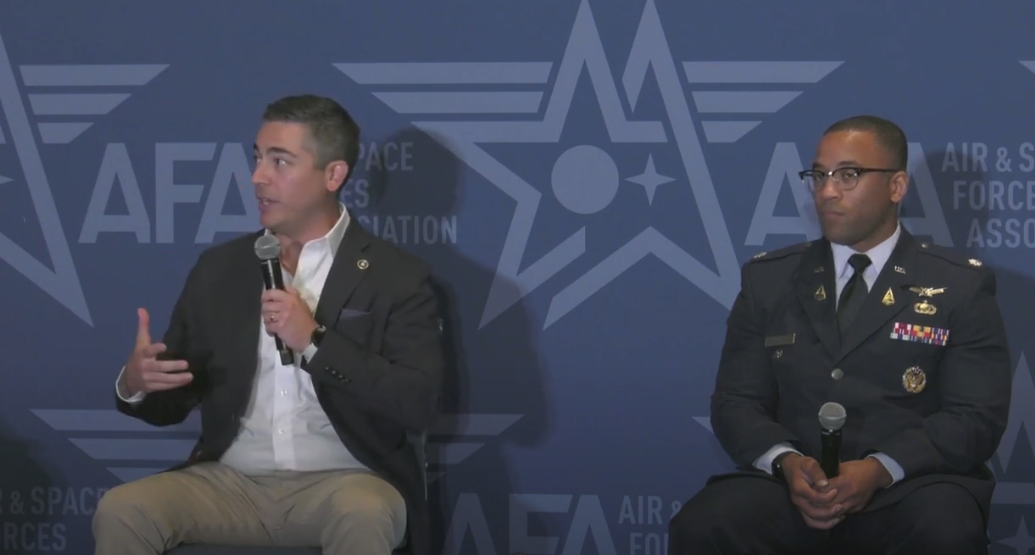

In closing, the legislators also echo comments made in August by John Sneden, director of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s propulsion directorate, who warned that the U.S. was “starting to lose our lead” in propulsion.

“If we do not continue to pursue advanced propulsion systems for our fighter aircraft, we risk opening the door for U.S. adversaries to overtake our advantages in fielded engine technology,” the lawmakers wrote.

Among the 49 members of Congress who signed the letter are three members of the Senate Armed Services Committee—Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.), and Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.); and the chair of the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.).

Six members of the House Armed Services Committee signed on as well—Rep. Michael Turner (R-Ohio), Rep. Robert Wittman (R-Va.), Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), Rep. Jerry Carl (R-Ala.), Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.), and Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.).