The Department of the Air Force needs to do a better job of identifying, recruiting, and mentoring Hispanic officers—especially at its very highest ranks, according to a new report and Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall.

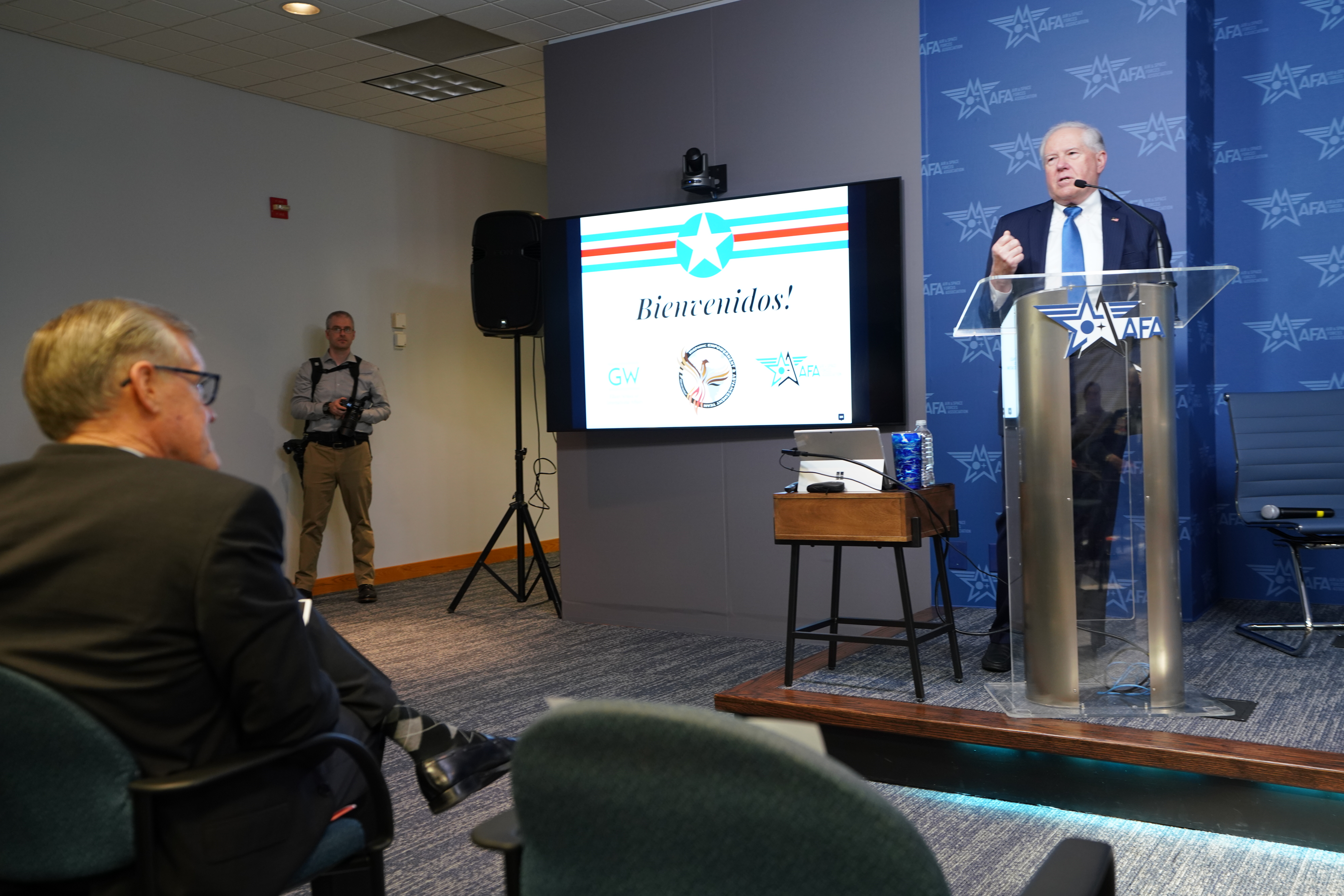

Speaking at a conference sponsored by the Air Force’s Hispanic Empowerment and Advancement Team (HEAT) and hosted by the Air & Space Forces Association on Oct. 14, Kendall highlighted the scarcity of Hispanic or Latino general officers as an issue that he and other Air Force leaders have been focused on as of late.

“[Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr.] and I briefed [Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III] recently, we went through our general officer posture basically, and the thing that jumped out at us was that we are not promoting enough Hispanics to the senior ranks,” Kendall said. “So we’ve got to ask ourselves: Why is that true? And we’ve got to go figure out what to do about it.”

According to the most recent data, just three generals in the Active-duty Air Force and Space Force identified their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino—less than one percent of the entire general officer corps. None are three- or four-star generals.

Getting a general officer corps that better reflects the rest of the Air Force and the U.S. won’t happen overnight, though. It will require a concerted effort to develop officers through the career “pipeline that delivers people to the top,” Kendall noted.

“We want to make sure that people are getting the opportunities that they have, and that there’s nothing that either the Air Force or individuals are doing that prevents them from reaching their full potential,” Kendall said.

Such an effort will likely entail a prolonged, multi-faceted process, and it will require individuals and leaders who can understand and appreciate the unique challenges that Hispanic service members face, Kendall said.

“One of the things I found is, as I’ve led diverse groups or been involved in diverse groups, is that if you don’t have people there who represent different segments of the population, so to speak, the people who don’t have those backgrounds—it never enters their head to consider things that would be obvious and immediate to people that do have that backgrounds,” Kendall said.

As an example, Kendall cited the success of HEAT, a barrier analysis working group, in introducing a policy change that allowed Airmen and Guardians to have name tags and tapes with accent marks.

Such proposals are necessary, Kendall added, to go along with efforts of leadership. Noting that he is a “WASP”—White Anglo-Saxon Protestant—Kendall praised the diversity of his own leadership team, including undersecretary Gina Ortiz Jones, the department’s first Latina No. 2. But he also urged conference attendees and other Hispanic Airmen and Guardians to propose and pursue their own ideas.

“We need your ideas. We need your input. We need your thoughts,” Kendall said.

A 28-item action list arrived later in the day with the release of a report from the Hispanic-Serving Institution-Air Force ROTC TableTalks (HART), a initiative from HEAT that surveyed Hispanic advocacy groups, recruiting leaders, AFROTC personnel, academics, and officials from Hispanic-serving institutions—colleges and universities with 25 percent Hispanic enrollment—to identify and address disparities facing Hispanic candidates for Air Force ROTC in particular.

“When we talk about tapping the unlimited potential … it takes 20 years to grow and develop a colonel,” said Lt. Col. Daniel Mendoza, one of the study’s authors. “How are our Hispanic and Latino students doing at the beginning of that journey, as they enter higher education, as they enter undergraduate programs?”

From a series of regional and national symposiums involving hundreds of participants, a group of 10 Airmen and Guardians, guided by academic advisers from some of the HSIs, produced a 59-page report breaking down the disparities facing Hispanic officers and Cadets—disparities the Air Force itself acknowledged in a inspector general report last year.

The report also included more than two dozen “implied tasks” for the DAF to pursue for the purpose of increasing Hispanic representation in Air Force ROTC, and especially for career tracks such as pilots or operators—fields that often feed into the highest ranks.

Those action items largely broke down across three areas—targeted outreach, resources aimed at specific issues, and “holistic individual development.”

For outreach, some changes can be as simple as providing recruiting material in Spanish. But more broadly, the Air Force needs to do more to “recruit the family,” Mendoza said.

“Our parents, our abuelos [grandparents], in many cases in the family, their word is law,” Mendoza said. “Their weight in terms of how we make these decisions in our lives holds a lot of influence. And if we’re not recruiting, if we’re not educating them and showing them what we as a professional organization are all about, it’s going to be difficult.”

It’s a dynamic Kendall noted in his own remarks, explaining that in his own experience, leaving home and striking out on his own “was nothing for me.” But in many Hispanic or Latino cultures, there is a stronger emphasis on staying close to and connected to family.

A key outreach tool cited in study is the Gold Bar Recruiter program. GBR takes 40 newly commissioned second lieutenants and places them in AFROTC detachments to recruit potential Cadets.

In addition to outreach, the department also needs to find ways to better allocate resources and increase flexibility so that Hispanic candidates aren’t denied opportunities. The report’s suggestions covered everything from paid internships in the summer to scholarships to scheduling and transportation accommodations for “cross-town” Cadets who don’t attend the university where the AFROTC detachment is located.

One of the biggest barriers, though, was cited by both the report and service members speaking with Kendall—the Air Force Officer Qualifying Test.

Since the 1950s, the Air Force has used the AFOQT to assess its officers, but its verbal portion has created issues for some who learned English as a second language.

“When we talked to ROTC detachment commanders, you could see the frustration on their faces,” Mendoza said. “They talked about these amazing young men and women that were in their detachment, who could communicate effectively, build a team, lead their folks, but because they could not pass a verbal portion of this test, [they were denied]. And oh, by the way, do the other services have similar tests for this to become an officer? … No.”

In 2021, after recommendations from HEAT, the department changed some of its rules around the test, reducing the amount of time candidates must wait before retaking it and allowing individuals to combine their best scores from different sections.

But still more can be done, Mendoza said, citing academic research that has found standardized tests are not always predictive of success.

Further reforms to the AFOQT is one of the top three action items identified by the report’s authors for prioritization, Mendoza added, alongside expanding the Gold Bar Recruiter program and refining the way the department collects and analyzes demographic data.