Having become a part of the Space Force on Oct. 1, the Space Development Agency expects little disruption—so to speak—to getting its initial constellation into orbit in time for military exercises next summer, SDA director Derek Tournear said recently.

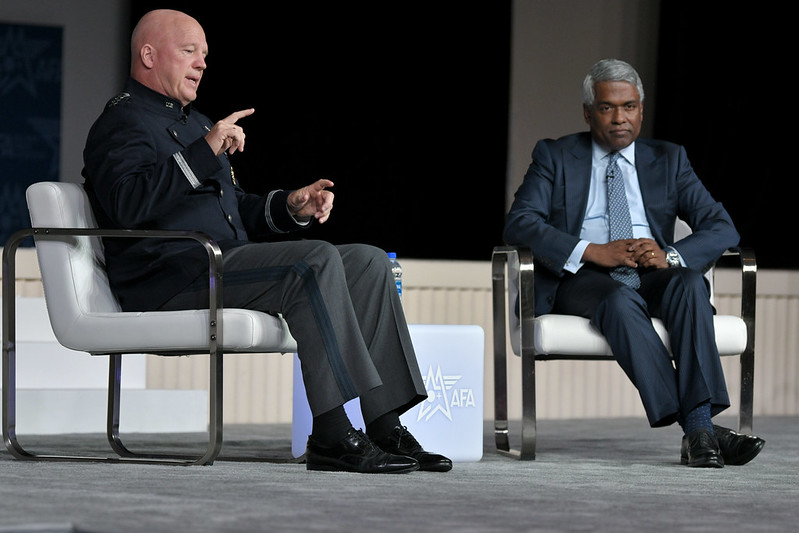

SDA predates the Space Force, though not by much—both started up in 2019—and SDA became “this disruptive innovator” with its concept for an “architecture based on proliferation and spiral development,” Tournear told reporters at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference. The idea is to field numerous, comparatively lower-cost data transport and missile tracking satellites and to refresh the constellation by de-orbiting some and adding more in two-year cycles.

As a new direct reporting unit in the Space Force, SDA’s reporting structure now parallels that of the service’s two other acquisition-oriented bodies, Tournear said—Space Systems Command and the Space Rapid Capabilities Office—by reporting to the assistant secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration for acquisition purposes, and to the Chief of Space Operations for administrative purposes.

In a separate event at the ASC conference, the first-ever assistant secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration Frank Calvelli complimented SDA’s “approach to doing business” for “building small” and “delivering capabilities faster,” he said. “I actually think that’s a model that we can take advantage of and actually push out across the organization.”

Tournear anticipated no personnel changes from the transition. SDA’s 210 people include uniformed service members, civilian government employees, and contractors who are looking ahead to the launches, scheduled to begin in December, of 28 satellites dubbed “Tranche 0” to test the concept of SDA’s planned National Security Space Architecture in low-Earth orbit.

Tournear said all of Tranche 0—a combination of data transfer and missile warning satellites—should be operational for demonstrations in the summer of 2023: “That’s when you have Northern Edge and a lot of these [other] exercises.”

SDA’s disruption in the form of proliferation and spiral development—a departure from so-called “exquisite” conventional military satellites developed over long timelines—couldn’t have taken place from within the Space Force, according to a theory Tournear attributed to the book “The Innovator’s Dilemma.”

Because an organization with “a de facto customer base” is inherently set up “to give that customer base exactly what it needs and what it wants … that means that you will give them incremental solutions,” Tournear explained—“because that’s what they’re used to. That’s what they expect. And you will continue to build off of that.”

For the disruption to take place, “you have to have a completely different set of values that will drive different processes and will utilize different resources that will give you a completely different solution,” he said. “Now, once that disruption happens, and then you get a new customer base that says, ‘OK, this is the right way to do it,’ or the existing customer base buys into that new model, then you can start to get into this model where you provide updates.”

Even though he expects the new approach “to need a lot of advocacy within the department and externally to make sure that industry can perform at these scales in these timeframes,” he senses that the Space Force is already onboard.

“Look at what Space Systems Command is doing with the [medium-Earth orbit, or MEO] missile warning, missile tracking layer,” Tournear pointed out. “They’re following the model of spiral development and this two-year timeframe to get things up and operational.”

With three organizations in the Space Force now tasked with acquisition, Tournear laid out his “bumper sticker view” of the breakdown of responsibilities, describing SDA as best suited to highly proliferated constellations in LEO; Space RCO as “very well suited for rapid acquisition of the prototype-type of solutions, especially on the classified side”; and Space Systems Command for “making sure that the overall architecture fits together.” Exceptions include the likes of SSC’s responsibility for the missile warning constellation in MEO.

A combined program office will function as “a technical interchange working group … to make sure pieces and parts are going to fit together when you’re done,” Tournear said. “For example, we have a deputy program manager from SSC … here with SDA to make sure that what SSC is building in the middle layer is actually going to fit in with us,” particularly “getting data formats that match up.”

The Missile Defense Agency also has a role in the working group because “eventually you want those data to actually support fire control, and the bread and butter is being able to take data from a lot of different sensors … and fuse those together for fire control solutions.”

One noticeable change will be Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David D. Thompson’s co-leadership with Tournear of SDA’s “warfighter councils.” The next one in March will define the minimum viable product for Tranche 2 of SDA’s planned data transport constellation.