For the Defense Department’s counter-WMD leaders, it’s a pivotal moment—and potentially a “wake-up call” for the U.S. to realize the importance of the mission, they told a House Armed Services subcommittee on April 1.

“I think the crisis in Ukraine and the blatant threats, really, by Russia of the potential use of chemical and biological weapons is opening everyone’s eyes to how much of a problem this is,” John Plumb, assistant secretary of Defense for space policy, told the HASC Intelligence and Special Operations subpanel.

For years, officials said, concerns over weapons of mass destruction were focused on their potential use by violent extremist organizations, like ISIS or al-Qaeda, or so-called “rogue states” like North Korea or Iran.

Recently, however, that has changed, as DOD has started to grapple with their potential use by adversaries with far greater capabilities—meaning a shift in priorities.

“From looking at closing the gaps that we have across the WMD spectrum in the investments, the main thing that we are pivoting from is concerns that it would be a non-state actor who would be using this to then really looking at state-based threats and the depth of the science and technology that they have available to them,” Deborah G. Rosenblum, assistant secretary of Defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological defense programs, told lawmakers. “And we can get into greater detail in terms of the specificity, but that is a dramatic pivot from a threat perspective.”

Russian officials have denied accusations that they have used chemical weapons, but independent observers have reported their use in Syria and Chechnya, as well as in poisonings in the United Kingdom. Now, Russia has accused Ukraine and the U.S. of developing biological and chemical weapons, an argument that Western leaders fear will be used as a pretext for Russia deploying such weapons of their own.

“I can say to you, unequivocally, there are no offensive biological weapons in the Ukraine laboratories that the United States has been involved with,” Rosenblum said.

Still, deterring Russia from using any WMDs in Ukraine presents a “challenge” to the U.S., Plumb acknowledged.

“I think the fact that the White House has used the megaphone of the United States of America to call this out is an important deterrent,” Plumb said. “It’s not just the administration, it’s also working with the Congress too, to rally the entire NATO alliance to kind of align against this. … We have this communication conflict that we really need to work on. On a readiness side, there is some argument to be made that better readiness and better training … helps deter. It’s necessary but not sufficient. But the more ready we are to engage in a zone like that, then perhaps the higher the threshold is for its use.”

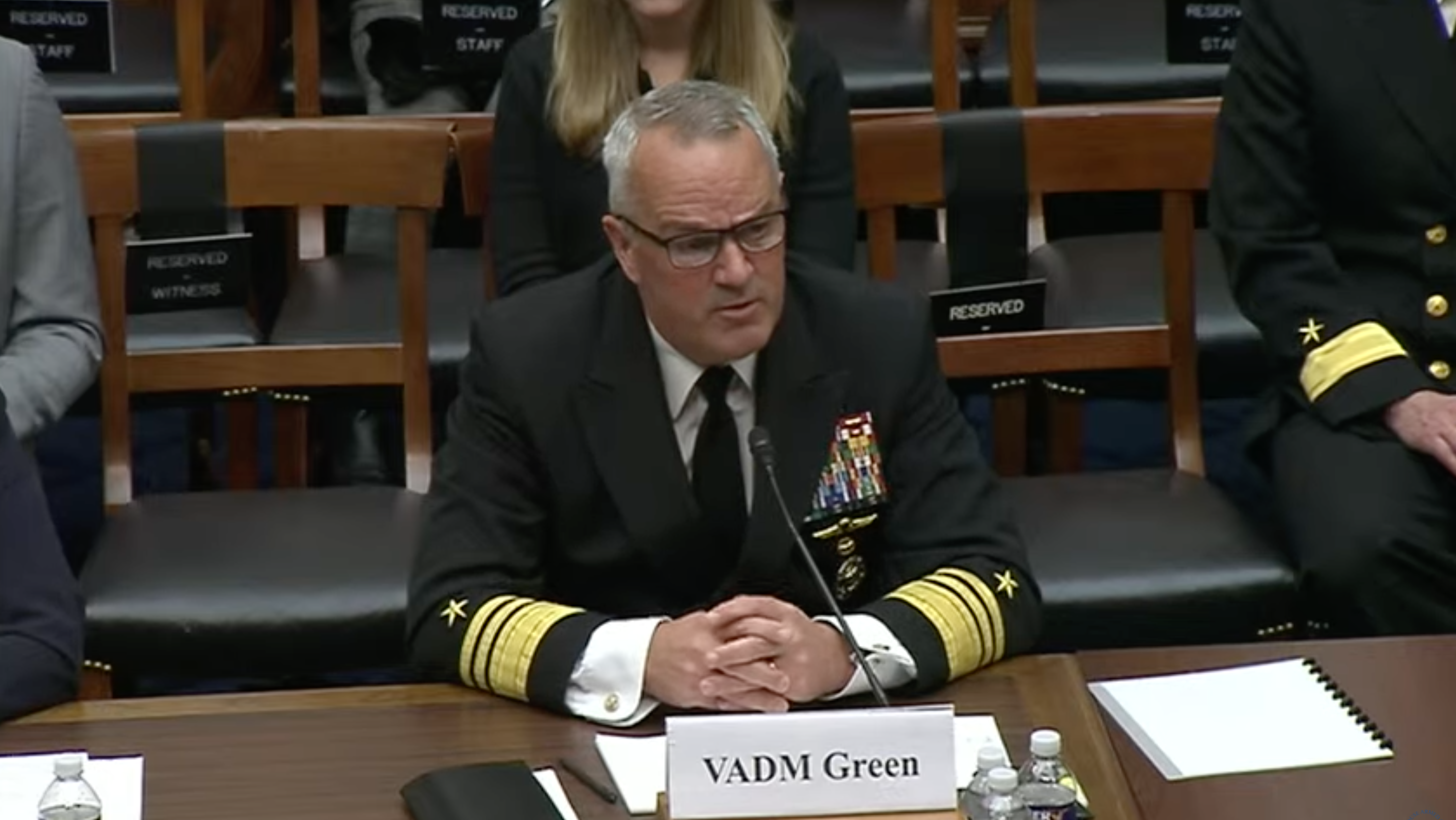

In order to be prepared should deterrence fail, Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III has directed that DOD integrate counter-WMD operations into “planning, resourcing, modernizing, and then more importantly, training and exercising, holistically,” said Vice Adm. Collin Patrick Green, deputy commander of U.S. Special Operations Command.

In 2018, SOCOM took over the lead role in organizing C-WMD efforts across the department. Now, four years later, Green sees the current crisis as a critical moment for the entire department and all of government to realize the urgency of the mission, just as they did after the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

“I think this is a wake-up call with regard to C-WMD, much like [counterterrorism] was,” Green said. “So I think the coordinating authority and the work that we’ve done here with my colleagues to recognize this threat, to plan for it, to modernize, and then to train and exercise, frankly, it’s a holistic approach.”