Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said he is more interested in quality systems that are able to deter an adversary than the size of the force structure, signaling an end to USAF’s pursuit of 386 squadrons as a force-sizing goal.

Speaking during a May 2 Brookings Institution webcast, Kendall said he’s “not focused on” the 386 squadrons goal, officially unveiled in 2018.

“I’m not focused on counting endstrength or squadrons or airplanes,” Kendall said, but rather on “the capability to carry out the operations we might have to support [toward] … defeating aggression. If you can’t … deter or defeat the initial act of aggression, then you’re in a situation like we’re seeing in Ukraine: a protracted conflict.”

Kendall said “nobody knows” how long Russia and Ukraine will “grind away at each other,” but “we don’t want to be in that mode.” Having a large force is aimed at such a prolonged conflict, but USAF “really needs, first and foremost, to deter that act of aggression, and if necessary, defeat it, and so I am more focused on that than I am on quantity right now.”

Kendall voiced high respect for former Defense Secretary James Mattis, but said he disagreed with Mattis’ emphasis on lethality of existing forces, saying it’s more important that forces be capable and resilient and be able to survive long enough to “get to the fight” and get home. “I put that very high on my list” of priorities.

He acknowledged that USAF is asking to spend a record amount on research and development this year, and reiterated that while he’s “comfortable” with the fiscal 2023 budget request, “I’m warning Congress … that hard choices are ahead” in 2024, in the form of more equipment retirements in favor of new development or production.

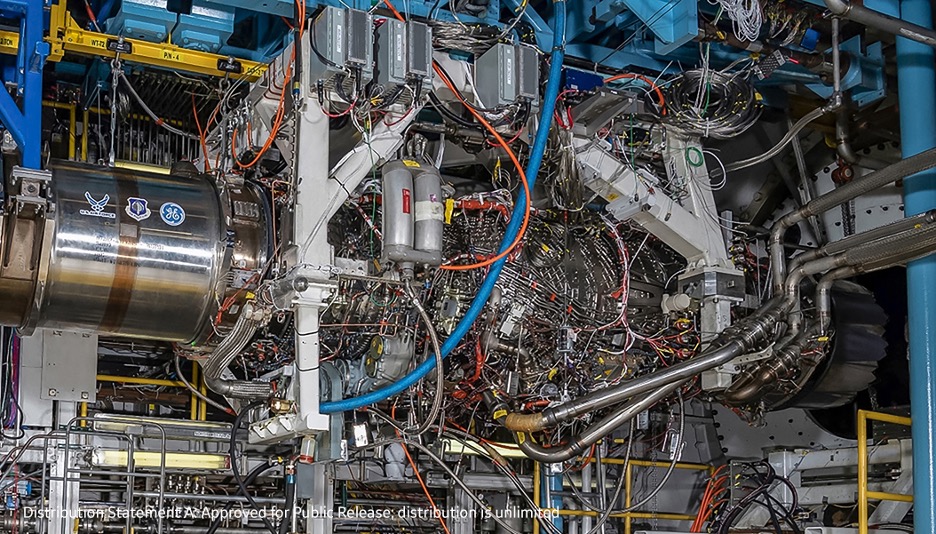

The future Air Force is also not far off, he said, noting that B-21 production money is in the FY’23 budget and that the Next-Generation Air Dominance aircraft and its family of supporting systems are “not far out,” as are programs like the Joint Advanced Tactical Missile, or JATM, which will equip USAF’s fighters mid-decade. These systems will “phase in” over “the next few years.”

As an example of the new approach, Kendall said the E-7 Wedgetail USAF will buy to replace the E-3 AWACS “is going to dramatically lower the cost of sustainment. So I’d rather have that platform, which also gives us a lot more capability … than the current fleet, even though the current fleet might be larger. So size isn’t … important to me. It’s quality and getting as much quality into the force as I can as fast as I can.”

Kendall noted that “an awful lot of the equipment that we have is old,” saying the average age of USAF aircraft is 30 years and rising.

The 386 squadrons goal—up from 312—was promoted by former Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson and former Chief of Staff Gen. David L. Goldfein. However, the goal was couched as an aspirational one and was not programmed with budget dollars.

Kendall’s also has little interest in technology demonstrations that don’t lead to “meaningful operational capability in the hands of operators as quickly as possible.”

Getting in the Game

Among Kendall’s seven operational imperatives are uncrewed aircraft that will escort manned aircraft. “I want to go directly to EMD [engineering and manufacturing development] on that,” he said. “The technology is mature enough that we can gamble on that, take some risks there, and move out quickly. So we’re not going to wait for a round of risk reduction experiments. We will conduct them in parallel with the work we need to do to get a platform moving forward.”

The Air Force will try to “synchronize efforts on things like mission systems—that can be upgraded over time—and software, that can be upgraded very easily over time, with hardware, which basically forms the basis by which you can then move forward and incrementally improve.”

Kendall said he wants to “get in the game, with something that makes a difference operationally, and then build on that.”

He said he envisions a three-year process between getting funded for a new capability and having something operationally usable. It’s riskier, though, because “the more aggressive you are with the risk you’re taking on design, the harder it is to be sure you have a stable design.” That’s needed, though, because China is moving out aggressively in fielding new systems, he said.

China’s timetable for fielding new equipment is “not better than ours. It’s probably not as good as ours. But they started earlier and they’ve been working aggressively on a larger number of things,” Kendall said.

He also said China is “not waiting to see what we do. They are basically figuring out what they need and what technology might offer them to meet their needs, and they’re moving forward.”

In Kendall’s experience with the old Soviet Union, Russia would not pursue a system if the U.S. was not already doing so, “because they figured we were so much ahead of them intellectually on weapon systems.”

The Chinese, however, “aren’t doing that. If they think something’s going to be operationally effective, they’re going to have it whether we’re doing it or not. So we have a tougher problem today than we had during the first 20 years of my career, unfortunately.”

Kendall believes China “has ambitions to be the great power on the face of the Earth,” and to do it, they must “displace the United States.” China’s ambitions have changed with its capability, he said, shifting from being a regional power to a global superpower. While not, perhaps, as interested as much in “territorial expansion,” China wants “as much influence as possible,” evidenced by their One Belt, One Road initiative.

“They want to set the rules for the economy, as much as anything.”

Kendall said his job is to provide the capability to deter and if necessary defeat “what a potential adversary might do.” And while the immediate threat might seem to be against Taiwan, “there are other places, like the Senkaku [Islands] in the South China Sea, where … aggression is possible also. So those are certainly within their near abroad.”

China has “articulated … pretty clearly … where they want to be my mid-century,” Kendall noted.

“I think we have to take them at face value. I made the mistake a few times during the Cold War, not believing what the Soviets were saying. Turns out that they meant what they were saying.”

Asked what technologies “excite” him as having the greatest potential, Kendall said, ”autonomous behaviors.” Artificial Intelligence is both a near-term capability and one that must be introduced as quickly as possible as a “decision-making” enhancement, he said.

Autonomous systems will “open up a whole range” of new tactical capabilities, he said, “and I don’t think we need to wait for more development on that.”

However, the technology “does invoke some really interesting questions about human control, and the degree of autonomy you’re really going to tolerate operationally.” If the U.S. doesn’t pursue this, “we’re going to lose” and “some of our competitors are not going to be as constrained as we are by those things.” The Air Force needs to “work those problems as we mature the capabilities.”

Kendall noted that he has worked as a human rights attorney and, “I am absolutely committed to the law of war and the assurance that we follow those rules. But we’re going to have to figure out how to vet that capability and hold people accountable for what they do … even though a machine may be acting as a proxy for the humans to some degree.” He added, “There’s work to be done there.”