The Senate passed the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) Dec. 15, sending the annual policy bill to President Joe Biden for his signature. But Biden could still opt to veto the bill over a controversial provision requiring the Pentagon to roll back its COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

The vaccine requirement helped lead to the near universal vaccination of the force, with nearly 2 million troops receiving one of the approved vaccines. But it also became a political flashpoint, sparking legal battles and resulting in thousands of service members being booted for refusing the shots.

Top Congressional Democrats agreed to the provision as part of a compromise NDAA unveiled Dec. 6, but the White House and Defense Department officials were not party to the deal, and have said it would be a “mistake” to drop the requirement.

Vetoing the entire bill would be a gamble for the president. Both the House and the Senate passed the NDAA by large enough margins—350-80 and 83-11, respectively—that a veto could potentially be easily overridden.

Hundreds of other policy decisions, report requirements, and directives are contained in the NDAA’s 4,408 pages. And while the bill does not appropriate funding—that is the job of the defense appropriations bill—it does authorize spending maximums and guidelines.

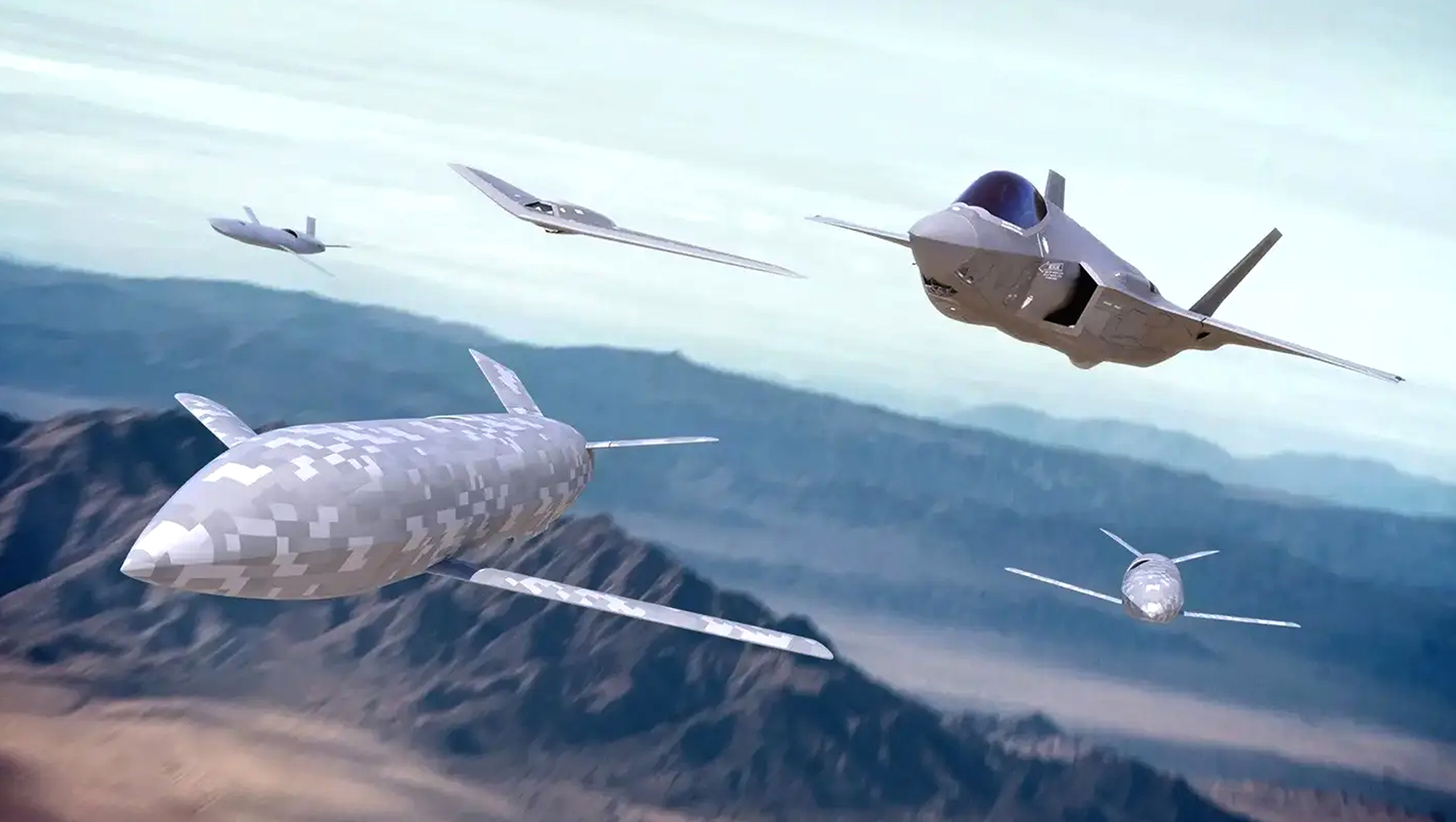

For the Air Force in particular, the bill would allow for the divestment of some aircraft, like the A-10, KC-135, and E-8 JSTARS, but blocks or restricts others, including F-22, F-15, E-3 AWACS, and C-40 aircraft.

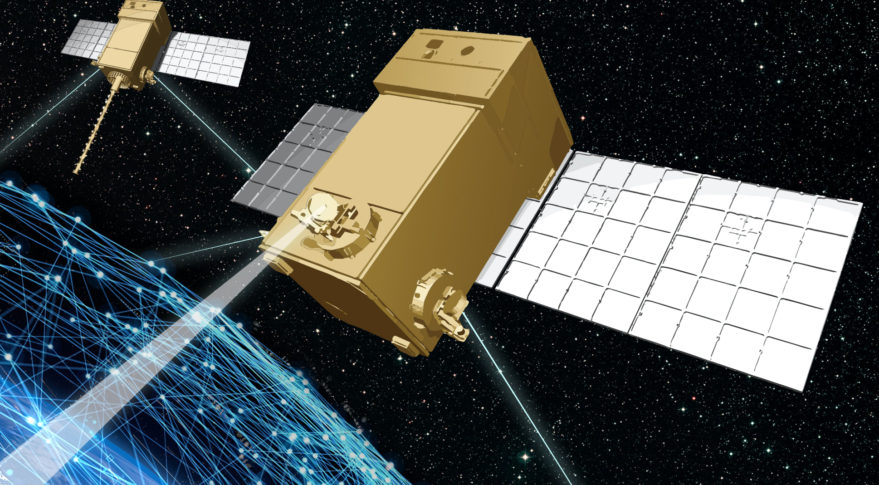

For the Space Force, the bill would require the development of “requirements for the defense and resilience of the satellites” before entering into acquisition programs, as well as the public disclosure of the department’s strategy for protecting and defending satellites in orbit.

For service members, the bill includes provisions that would extend Pentagon authorities to temporarily increase the Basic Allowance for Housing in areas where prices increase dramatically, require a broader study of how BAH is formulated, and authorize an evaluation by the Comptroller General on each service’s marketing and recruiting practices.

The 2023 NDAA includes a top line of $858 billion for national defense, including $816.7 billion for the Pentagon. That funding would need to be appropriated in a spending bill that is still under negotiations in Congress. Leaders there announced Dec. 13 that they had agreed to a “framework” for an omnibus spending bill that would fund the entire federal government, but details must still be worked out.

In the meantime, the continuing resolution currently funding the government fiscal 2022 levels was set to expire after Dec. 16. The House passed another CR Dec. 14 that would last through Dec. 23, the end of next week, and the Senate agreed to it later Dec. 16.